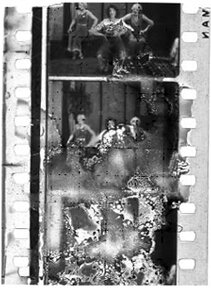

In 1978 a startling discovery elated the small world of film preservationists, restorers, and scholars. A trove of long lost original nitrate copies of silent movies was uncovered at a construction site in Dawson City, Alaska. Among them were long lost films starring Pearl White, Harold Lloyd, Douglas Fairbanks, and Lon Chaney. The permafrost had preserved them for 50 years after they had been tossed into an empty, abandoned swimming pool and covered with fill dirt.

How did these cinema treasures get to Dawson City? The story says a lot about the path of film preservation. Dawson City, it turns out, is at the end of the movie theater print circuit. Prints are usually shipped from theater to theater in an unchanging pattern. A new print starts in a big city like Seattle. From there it might go to Spokane, and then to Bellingham; next on the list might be Fairbanks, then Nome and finally Dawson City.

By the time a print arrives in Dawson City it has been run through a couple dozen grinding projectors by gum chewing teenage projectionists. It has been broken, spliced, cut to insert trailers and re-spliced and re-broken. It has so many scratches the Dawson City audience probably thinks it is always raining in the lower 48.

When a print ends its run in Dawson City it’s not worth shipping back. At first, the local movie theater donated the prints to the library. But in 1929 the library decided they didn’t want a lot of highly flammable nitrate prints in their stacks. They heaved them into an abandoned swimming pool where they were used as fill trash.

Trash: that’s the secret of film preservation. The great find of 1978 happened because somebody was digging a new foundation and unearthed a movie burial ground. The permafrost layer in the fill dirt above the movies had preserved them as good as in a temperature-controlled vault. They were given to the Library of Congress and restored.

Many assumed-lost movies have been found this way. They turn up in Uncle George’s attic or in Grandma’s garage. Movie making has always been a seat-of-the-pants occupation balanced between tight budgets and the rush to make money. Studios rarely kept archive prints. It was just another expense nobody wanted to pay for.

And why bother? The film negative was stored in the lab vault under lock and key and temperature control. That is, if the producer paid the rent and sprinkler pipes didn’t break and flood. Hollywood pros speak the name Roger Mayer with reverence. He was in charge of the lab at MGM and one of the first people to realize the tremendous value of carefully preserved movies. He convinced the studio to let him reprint many old ones on modern film stock. Before celluloid replaced nitrate as the base on which moving pictures were photographed, even carefully stored movies could turn to dust.

Every film student knows the story of Robert Flaherty traversing the Arctic making his famous documentary, Nanook of the North. After a year of shooting, he gathered all the film in his cutting room to edit and lit a cigarette. Poof! In 30 seconds everything was gone (Flaherty went back a second time and reshot the film).

Once missing films are found, the science and art of film restoration takes over. The caisson where most of this happens is an underground labyrinth at the Eastman House of Photography, in Rochester, NY. (There’s no reason it is underground except George Eastman’s old mansion is on top of it). Technicians have special machines for cleaning, lubricating, and printing. Old images are not the only problem. Film shrinks over time and will not fit the sprocket gears of newer machines. Restorers are crafty folks who know secret tricks like wet gate printing and high resolution video manipulation. Sometimes they must restore one frame at a time. They are true alchemists.

The next time you see Marty Scorsese on TV standing at one of those black tie parties announcing a brand new print of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, think of Dawson City, The Eastman House, and all those people who knew enough to read the labels on the cans before cleaning out Grandma’s garage.

(A big thank you goes out to for today’s guest post. You’ll find him over at Movie With Me where I – Bill – am an occasional contributor. Here is how Roberto describes himself at Movie With Me: “Resident Curmudgeon & Film Buff

“As a long time Hollywood producer, I love the internet because there are no rules, no gatekeepers, no stupid executives whose only skill is looking good in a suit. And I love film. The ones that are great, and the ones not-so-great that have moments of inspiration or brilliance. Making a movie is a roll of the dice. Once you have actors and tempers and weather you never know what will happen. The only thing you can be sure of is it will never turn out exactly the way you planned. I salute anyone who tries, and I try to sing the unsung because they too deserve a little glory for attempting the impossible. “

Many, many thanks!)

Directed by Henry Hathaway

Directed by Henry Hathaway