Directed by Sergio Leone

Directed by Sergio Leone

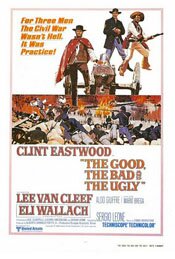

One of the best, and oddest, westerns ever made is The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo). It’s hard to imagine anyone making a movie like this today. It’s too long (it would be argued). Some of the scenes, even shots, are too long. Gee, it takes 30 minutes to introduce the three primary characters. What’s that about?

Well, it’s about imagery. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is less about telling a story (though it does do this in its roundabout way) than it is about the myths inherent in westerns, and the iconic imagery they use.

It’s a bit ironic that a film like this (together with Sergio Leone’s previous two westerns, A Fistful of Dollars and For a Few Dollars More) would initially be celebrated as a new “modern” western because of its gritty realism when it is a film that is anything but realistic.

This is not a disparagement. But the movie isn’t concerned with realism, though it does take an non-Hollywood approach in making its characters and scenes look dirtier and more rugged than was the norm then. It’s really concerned with seeing or, more precisely, perception – specifically, ours as an audience.

As Roger Ebert has pointed out, there are many scenes, including the very opening, where Leone shows us a shot that we assume is one thing but, a moment later, turns out to be something else because something or someone moves into frame.

In fact, the screen’s edges are the borders of what we see; we are limited by the camera.

Another example of this is when Tuco (Eli Wallach) and Blondie (Clint Eastwood) are walking through a green, forested looking scene. Eastwood’s Blondie is cautious but Tuco assures him not to worry. A moment later, a Union soldier appears with a gun, then several more soldiers appear. They have been there all the time – out of frame. As Tuco and Blondie are herded forward, they take a few steps and are suddenly looking down on and walking into a sprawling camp of union soldiers, a scene primarily coloured in the dark blue of the soldiers’ uniforms and the slate coloured dusty ground. Once again, this is something that was there all the time – just out of frame.

Shortly thereafter, we see another shot where the foreground is the blue and slate of the camp, but the background is the greenery of the setting the characters have just left. In this shot, we finally see a more complete view of the entire setting. Until now, our view has been limited by what the camera has shown us. In a sense, we go from a subjective to an objective view and we see they are not the same.

This is fine as far as sets, shots and character point-of-view go, but Leone carries it further, I think. This subjective perception carries through to the characters as well. In those first thirty minutes of the film, Leone takes great pains to draw his characters as the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. But once the film proper gets going, these simplistic characterizations get muddled a bit, particularly in the character of Tuco.

Those initial scenes characterize Tuco, Blondie and Angel Eyes (Lee Van Clief) in a very uni-dimensional fashion. But as the movie moves the characters through its western landscape we’re given scenes that muddy these. Some scenes affirm they are good, bad or ugly, others undermine them. The characters all seem cold and self-contained yet we get scenes with suggestions of something approaching warmth – a bit more human. Tuco is probably the most morally ambiguous of the characters – sometimes he’s mean, sometimes he seems good, sometimes he’s good but we know its an act. So who are these men?

Everything is determined by the limits of our knowledge – conditioned by the limits of what we perceive, like the frames of the camera.

This is also mirrored by the quest the men are on for the $200,000. Individually they can not find it because individually none has all the information.

Tuco knows where the graveyard is but only Blondie knows what grave it is in. No one, including the audience, has the complete picture and they, like us, are often fooled because of what they are not aware of.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly was chosen as a western partly, I think, because of what we think we know of them. The template is imbedded within us. Leone uses this, making tremendous use of mythic western imagery and our assumptions. He gives us a western that plays like one but, at the same time, somehow doesn’t. It’s as if there is something right and wrong about it at the same time.

And then there is the music

On another point, the music by Ennio Morricone in this western is fabulous. If Leone is using mythic elements, he’s also chosen to use music as a way to not simply support the story but to write it indelibly in our memory.

Sound and smell prompt memory better than any of the other senses, so while film is a visual medium it is often through music that it stays with us.

The scene of the prisoner soldiers playing melancholy music while – out of camera frame – Tuco is being brutalized is a haunting, unforgettable moment.

As is the scene where, in the circle in the centre of the graveyard, the three main characters face off against one another while Morricone’s music plays, brash and thrilling. It, too, is unforgettable. In both cases the scenes are striking because of what they concern and how they are shot. But it is the music that makes them stay with us.

And then there’s the DVD

The original MGM disc is good in the sense it gives us the 162 minute version of the movie, as well as 14 omitted scenes (only in Italian, but with English subtitles). These were intended to be in the film. Unfortunately, they are not incorporated. One in particular with Lee van Clief is especially significant as it undermines our perception of him as “the Bad.”

I read somewhere recently they had brought in some of the still available actors and to lay in the English voice work on these scenes in an attempt to restore the film to its original length. I certainly hope this is true and it works.

Update (August, 2007): And now that edition is available — The Good, the Bad and the Ugly – Special Edition. It is cleaner visually and has the earlier versions omitted scenes added, now running 179 minutes. It looks and sounds as if considerable work has been done to the film. The end result is fantastic.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is not just one of the great westerns. It’s one of the great movies. For me, the proof is in my ability to see it again, enjoy it again and, to my delight, find new aspects to it I hadn’t seen before. It’s not just an enjoyable film, it’s a rewarding one.

Though I’ve seen it many times, I will see it again and again.