With a movie as good as Hero, where do you begin? There are so many elements, so many perspectives, so many levels that warrant lengthy discussion it’s almost impossible to start.

So I’ll begin by first saying my knowledge of China, it’s history and culture and everything else, could be put on the head of pin and still leave room. My ignorance is boundless so anything I have to say comes from a totally western perspective.

But that’s okay because, like any worthwhile art, Hero is a movie for everyone and likely becomes more interesting as more perspectives and interpretations are brought to it.

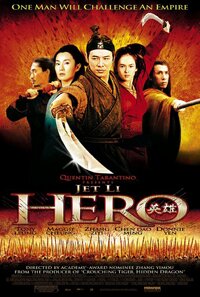

Set roughly 2,000 years ago in China, Hero is about the beginning of China’s unification as a single nation under the harsh leadership of the King of Qin (played by Daoming Chen).

As mentioned, I know nothing of China but my guess is that Hero is a little bit of history, a little bit of legend and a fairly loose interpretation of both.

As mentioned, I know nothing of China but my guess is that Hero is a little bit of history, a little bit of legend and a fairly loose interpretation of both.

The king has his enemies and the movie begins with a man called Nameless (Jet Li) coming to the emperor to say he has destroyed his three greatest enemies: Sky (Donnie Yen), Broken Sword (Tony Leung Chiu Wai) and Flying Snow (Maggie Cheung). Nameless, in the emperor’s court, tells the king of how he killed these three.

While comparisons have been made between Hero and Akira Kurosawa’s Rashoman, this is a bit misleading. They are similar, however, to the extent that Hero tells the story of the three enemies and their ruin from different perspectives (including the king’s) and not necessarily truthfully. (As Yunda Eddie Feng at suggests, a better comparison might be to The Usual Suspects.)

The film, then, moves inexorably toward its truth and this is where the film’s title, Hero, becomes interesting. Who is the hero? There appear to be several.

The film, then, moves inexorably toward its truth and this is where the film’s title, Hero, becomes interesting. Who is the hero? There appear to be several.

I understand that ying xiong doesn’t distinguish between singular and plural (as we do with the English hero and heroes). I don’t know, but it is certainly one of the interesting aspects of the film – what is a hero and what makes him or her heroic?

In the movie, despite it’s Hong Kong martial arts and swordplay, the implicit violence of swords is downplayed.

One of the film’s keys is the idea of swordsmanship and calligraphy being connected. Calligraphy is a hugely important element of the film.

One of the film’s keys is the idea of swordsmanship and calligraphy being connected. Calligraphy is a hugely important element of the film.

The movie overall is lyrical, even poetic. Similar to Ang Lee’s approach in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, the film is more interested in the romance of its story than in any other element. It’s from this romance the lyricism is drawn and it is what unifies the entire film.

And while there is romance of the love variety, the greater romance is in the view of heroism – sacrifice and honour.

For me, the best martial arts films are like the best westerns. In fact, I think they are essentially the same genres but from different (though dovetailing) cultures.

Both are at their best when informed by morality and romance. I would argue (and have argued) that these two genres (martial arts and westerns) are the same, and are essentially romantic, moral tales given a deceptive high adventure gloss.

Both are at their best when informed by morality and romance. I would argue (and have argued) that these two genres (martial arts and westerns) are the same, and are essentially romantic, moral tales given a deceptive high adventure gloss.

From my admittedly limited perspective, what Hero most reminds me of are the great films of Sergio Leone like The Good, The Bad and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West. It’s not just in the type of story but also the way it is told.

Like Leone’s films, I can’t image Hero in anything but widescreen. The cinematography of Christopher Doyle is breathtaking.

The way scenes are framed, spread across the screen, elements juxtaposed, gives the movie its epic and legendary look.

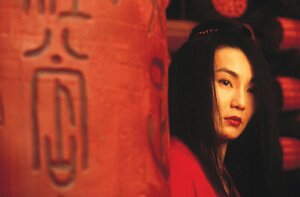

And while I see many movies use colour (usually in an annoying way), in Hero colour literally tells the story.

And while I see many movies use colour (usually in an annoying way), in Hero colour literally tells the story.

Working in tandem with the wonderful music of Tan Dun, the story gets told almost without the necessity of words.

Hero isn’t just a good movie, it’s a great movie. It’s epic and rich and a veritable visual feast … even if, like me, you know next to nothing about China.