Call it a tall tale, a shaggy dog story or any of the other variations, this is a movie that uses exaggeration and fable to tell a story that centres around another romantic tall tale. And it works much better now, ten or more years later, with distance from the marketing and celebrity media atmosphere that surrounded it when released.

Call it a tall tale, a shaggy dog story or any of the other variations, this is a movie that uses exaggeration and fable to tell a story that centres around another romantic tall tale. And it works much better now, ten or more years later, with distance from the marketing and celebrity media atmosphere that surrounded it when released.

By the way, they also created their own hand-cranked camera to shoot the flashback-like scenes that illustrate the telling of the legend of the gun called The Mexican.

The Mexican (2001)

The Mexican (2001)

Directed by Gore Verbinski

Does anyone play a blonde airhead better than Brad Pitt? Male or female, I think he’s got that one down better than anyone because he makes it seem so genuine. He certainly does that as Jerry Welbach in The Mexican.

And while many would take that as an excuse to rag on Pitt and his acting skills (he is, after all, a pretty boy and part of that famous couple — a big, big celebrity guy), he’s a much better actor than he gets credit for, at least in roles like these.

Here, the role requires a degree of nuance because the seeming airhead he starts as is not the same guy at the end.

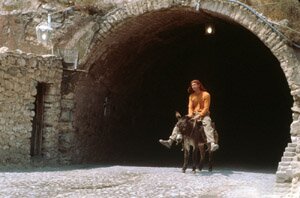

Jerry (Brad Pitt) in Mexico with his rental car – an El Camino!

It isn’t that the character changes so much as it is that more of him is revealed as the movie progresses. It turns out Jerry, while no genius, isn’t a dummy either. He’s just a guy who suffers from what might be called attention deficit disorder (ADD). He’s off in the clouds; he does a poor job of focusing.

But the real reason for all the trouble he manages to create for himself and others is that he is a trusting innocent, despite the world he inhabits. And it gets him in really big trouble.

He also has the patience of Job given that he has hooked up with Samantha Barzel, played by Julia Roberts, and she is about as annoying a harridan as you’ll ever find. It must be love that unites them because there is no sane reason for remaining with a shrew like that.

Roberts, to give her credit as well, is about as infuriating a woman as you’ll find in her performance as Sam. Her character is also an innocent, though of another kind. She isn’t trusting, initially, the way Jerry is. Still, her first response is to believe whatever she is told — unless it comes from Jerry.

However, it is really only when they are together that the two are so deranged.

Bickering Sam (Julia Roberts) and Jerry.

Pitt’s Jerry, apparently not too bright and having a stooge-like ability to screw up (almost like a Chaplin character), is in debt to some rough characters.

He made a balls-up of what should have been his last job to work off the debt, so they give him another: go to Mexico, pick up an antique gun called The Mexican and bring it back. Simple enough.

But not for Jerry. Sam tears a strip off him because she wants to go to Vegas, seemingly indifferent to the fact that if Jerry doesn’t do the job he’ll likely be killed.

Jerry heads to Mexico and screws up at every turn.

This movie got a rough ride when it first came out though I’m not quite sure why. One complaint was that with two big stars (Pitt and Roberts), why were they not on screen together more? The movie is wrong-headed that way, it was argued. I sort of understand that argument because I argued something similar about the use of Bogart and Bacall in Dark Passage.

Jerry travels by burro.

But I think you would need to have had Pitt and Roberts in a completely different movie to make the kind of film that places them together in most scenes.

In The Mexican, they are so infuriating and irritating together, given their characters and the nature of those characters’ relationship, we all would have fled the theatre screaming.

I like the two storylines the characters follow in their separate ways. The line Pitt’s Jerry follows slowly incorporates the story of the gun, the legend of the The Mexican, and we see there is more to Jerry than we initially thought.

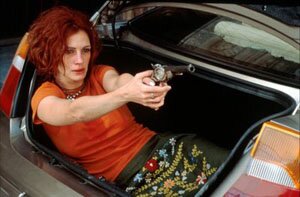

Robert’s Sam gets involved (unwillingly, at first) with a gay hit man (James Gandolfini) who kidnaps her because whoever “has the girl” will have the gun, the assumption being that Jerry will want her back (which he does).

Legendary gun, The Mexican.

There is also an assumption, by most of the other characters, that Jerry’s problems in bringing the gun back are because he has his own plans for it, since it is worth quite a lot. They think he plans to keep it and sell it himself.

The two storylines comment on one another because, as the stories progress, the characters refer back to one another, particularly Robert’s Sam in her conversations with Gandolfini’s character. (And Gandolfini is so good in this movie, you should at least see it for his performance.)

While there are some very funny scenes in the movie (it’s a comedy, of sorts) it is more fun than funny and you get a sense the making of it was probably a lot of fun. And Brad Pitt shows he plays comedy very well.

Sam’s experience with The Mexican.

To tack a label on it, it’s a comedic adventure. It is also fantasy and fable.

Like the legend of the gun The Mexican, the movie The Mexican is a tall tale, one that knows it is a tall tale and expects the audience to realize it’s a tall tale. Characters and situations are exaggerated, less for inflating the tale as is often the case as for the humour and fun it puts in its story.

It is the quality of innocence, or purity, that pulls Jerry and Sam together and unites them with the legend of the gun, The Mexican.

I haven’t seen this movie for a few years and I’m glad I went back and watched it again. I had forgotten how much I liked it. In fact, more than ten years after its release, I like it even more.

(Originally posted August 10, 2011.)