I haven’t seen A.I.: Artificial Intelligence in a few years so I watched it again last night. My memory is poor but based on what I wrote (below) in 2002 and my vague recollection, this was a Stanley Kubrick project that never saw the light of day. (The Wikipedia entry suggests Kubrick himself felt the subject might be better suited to Spielberg.)

A brief online scan shows that since the DVD was first released back in 2002, there haven’t been any other editions. I don’t believe it is available yet in HD. That seems odd since it seems the kind of movie suited to HD. Here’s what I wrote back in 2002:

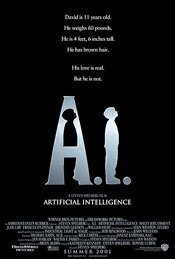

A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (2001)

While it is a flawed film, I think A.I.: Artificial Intelligence is the Steven Spielberg film I’ve most enjoyed. Like the Andrew Niccol film Gattaca, it’s a science fiction film that is about something and, like the best science fiction, it’s not about science but how we respond to science and what it creates.

It’s also a great movie to set against Spielberg’s earlier Close Encounters of the Third Kind in that the perspective is so different.

In a way, it relates to Spielberg’s earlier films in the way Shakespeare’s The Tempest relates to the earlier Shakespearean romances. The bright, awe-struck sensibility of a young man is now replaced by a darker (but not pessimistic), somewhat world-weary view of an older man. This is what happens when you make movies like Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan. While hope may remain, it has been conditioned by the darker aspects of reality, by an awareness of consequences that linger despite overcoming evil.

Of course, this is the movie that has caused so much discussion about what Stanley Kubrick would have done had he made the film. There seems to be a belief among some that Kubrick would have made a better film. I don’t think so, and I think Kubrick knew it.

Of course, this is the movie that has caused so much discussion about what Stanley Kubrick would have done had he made the film. There seems to be a belief among some that Kubrick would have made a better film. I don’t think so, and I think Kubrick knew it.

In fact, I think this movie is as good as it possibly could have been, and is probably much better than many think it is, precisely because it’s informed, to varying degrees, by both men. Spielberg’s mastery of a child’s viewpoint is what redeems the bleak world of a Kubrick production.

Kubrick’s masterful way of creating an almost Zen-like clarity of darkness defuses what could easily have devolved into an almost Disney-ish sentimentality. Together, the Spielberg and Kubrick sensibilities negate the excesses of the other and create a dark vision we can actually enter, identify with and travel along with.

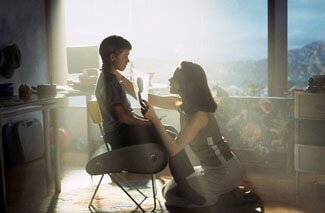

It results, however, in a few jarring moments. In the first act, Spielberg gives us a pristine homage to the Kubrick style. In fact, it’s hard to image this is Spielberg directing and not Kubrick. The scenes are austere, cold, clinical, dispassionate. In the same way that Kubrick sets up a story by almost laying cards unemotionally on the table, Spielberg creates a collage of scenes almost documentary style. There are odd angles, off-putting lighting, and brief dialogue exchanges with awkward pauses that create a sense that we are seeing things voyeuristically, at imperfect but opportunistic moments.

It results, however, in a few jarring moments. In the first act, Spielberg gives us a pristine homage to the Kubrick style. In fact, it’s hard to image this is Spielberg directing and not Kubrick. The scenes are austere, cold, clinical, dispassionate. In the same way that Kubrick sets up a story by almost laying cards unemotionally on the table, Spielberg creates a collage of scenes almost documentary style. There are odd angles, off-putting lighting, and brief dialogue exchanges with awkward pauses that create a sense that we are seeing things voyeuristically, at imperfect but opportunistic moments.

In Kubrick films, he sometimes seems to show us moments that are not only not the moments we’re use to seeing, but the moments that occur between them. In other words, he uses the material others put on the cutting room floor, and discards what others would have used.

And then we’re into the second act and suddenly in Steven Spielberg’s world. The austerity is gone; it’s all adrenaline now. It’s the man who makes movies like Jaws and Jurassic Park rather than The Shining. I think this is because in the first act we’re seeing how we react to David, this robotic boy who seems so human. The focus is on our response (not as an audience, but as a individuals who make up a society) and that is pure Kubrick.

And then we’re into the second act and suddenly in Steven Spielberg’s world. The austerity is gone; it’s all adrenaline now. It’s the man who makes movies like Jaws and Jurassic Park rather than The Shining. I think this is because in the first act we’re seeing how we react to David, this robotic boy who seems so human. The focus is on our response (not as an audience, but as a individuals who make up a society) and that is pure Kubrick.

In the second act we see how we, as human beings (identified now with David) are affected by this response. It’s terrifying; it’s baffling. It’s nightmarish, and this is what Spielberg gives us, in the Spielberg style.

In the third act, we’re into something altogether different. It’s a strange fusion of Spielberg and Kubrick, of Close Encounters and 2001: A Space Odyssey. The end is mysterious but it’s also hopeful, in an odd and equivocated way. Frankly, I’m not quite sure what to think of the ending.

Spielberg hedges on the bleak ending but that is not a bad thing because the obligation to Kubrick, I think, conditions and mutes a happy ending. It’s probably also muted because of Spielberg’s awareness of the Holocaust where, though the evil is defeated, its consequences remain.

When I picked up A.I., I didn’t expect much. Following the utter rubbish of big DVD releases like Star Wars: the Phantom Menace and Planet of the Apes, I was expecting another great DVD package of a truly awful film. What a wonderful surprise to find a really good movie was on this 2-disc set. The one thing to be aware of is there are two versions out there: widescreen and pan-and-scan (full frame). But the packaging doesn’t really make it obvious so take care to pick up the version you prefer. (Hopefully, you aren’t one of those barbarians that prefers the full frame.)

When I picked up A.I., I didn’t expect much. Following the utter rubbish of big DVD releases like Star Wars: the Phantom Menace and Planet of the Apes, I was expecting another great DVD package of a truly awful film. What a wonderful surprise to find a really good movie was on this 2-disc set. The one thing to be aware of is there are two versions out there: widescreen and pan-and-scan (full frame). But the packaging doesn’t really make it obvious so take care to pick up the version you prefer. (Hopefully, you aren’t one of those barbarians that prefers the full frame.)

(This review was written in March of 2002.)

See also:

- Super-Toys Last All Summer Long (story A.I. is based on)

- A.I. – Artificial Intelligence on Amazon (Widescreen Two-Disc Special Edition)

As I recall, Kubrick actually shot some test footage, but decided to wait and see where the new digital film technology was going.

A Kubrick version would have been interesting. It’s hard to see it being a better film, given that SOME sense of humanity would seem to be required.

Yes, a Kubrick version would be interesting. But it would have been very cold (which is what the beginning of Spielberg’s is like, a bit). His influence, though, probably helped this one from going to far into Steven Spielberg country.