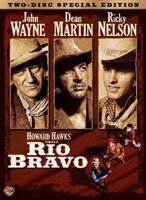

Directed by Howard Hawks

One of the more curious of the great westerns has got to be Rio Bravo. Referred to by some as an “indoor western,” there’s almost a stage quality to it as most of it plays on sets and very little plays on location.

One of the more curious of the great westerns has got to be Rio Bravo. Referred to by some as an “indoor western,” there’s almost a stage quality to it as most of it plays on sets and very little plays on location.

At least, that’s how it appears. It comes across this way because it’s largely dialogue. There are no sweeping expanses of western landscapes with riders on their horses. While there is a shoot-out, there is no great, orchestrated scene such as you find in Sergio Leone movies.

In fact, there is a very simple plot – a few good guys catch a bad guy and try to keep him in jail while the bad guy’s friends and big boss try to get him out.

What the movie is really concerned with is its characters, their relationships and how they behave. And that’s where the movie excels; it’s why it is so good.

With the exception of the sheriff, John T. Chance (played by John Wayne), all the main characters are outsiders.

They are people who have one thing or another working against them, something keeping them on the social fringe.

The primary one of these is Dean Martin as the drunk known as Dude (or ‘Borachón’).

The movie begins with Dude trying to enter a saloon surreptitiously. He keeps rubbing his mouth, eying the room and particularly eying the whiskey. He needs a drink desperately but it becomes clear that while there is liquor everywhere he has no money to buy any.

Dude is finally noticed by Joe Burdette (Claude Akins) who is standing at the bar. Wordlessly, Joe decides to taunt Dude, finally throwing a coin for a drink into a spittoon at Dude’s feet in order to see him humiliated.

Dude wants a drink so badly, he accepts the humiliation and gets down to retrieve the coin. Then he stopped and looks up at the towering figure of the sheriff, his friend John Chance.

And this is the movie. Joe ends up killing a man thus becoming the film’s McGuffin. But the movie is really about Chance and Dude and how Chance helps Dude recover his dignity and place.

The other three outsiders who become part of the small group who revolve around Sheriff John Chance are the crippled man Stumpy (Walter Brennan), the single woman, gambler/showgirl Feathers (Angie Dickenson) and the baby-faced young gun Colorado (Ricky Nelson).

The movie becomes a film about nobility and dignity – how they are lost but more importantly how they are recovered. In this sense, it’s like most great westerns in being concerned with American idealism and the mythology of the West as a place for second chances.

The action sequences are therefore few and almost done in an offhand way – sort of to get them over with and move on.

Director Hawks lingers when it comes to people behaving – acting and reacting.

Rio Bravo also illustrates Hawks’ view that people worked best together, as a team supporting one another, but only when everyone is cool and disciplined. In fact, this is what Dude needs to reacquire.

Wayne’s sheriff gives him the chances to do this but, at the same time, he doesn’t coddle or nurse him. It’s a ‘tough love’ approach, so to speak. He seems to say, “I’ll give you the chance but it’s up to you to take it and to do something with it. Don’t look to me to do it for you.”

It’s in taking those opportunities the sheriff offers that their dignity is regained.

It’s in taking those opportunities the sheriff offers that their dignity is regained.

And this is sort of the romantic view of what America is all about: the chance which, if taken, can give a person their individual nobility and dignity. Harsh though it may be, it is ultimately restorative.

One of the amazing things about Rio Bravo is how unassuming it appears. It comes across as a simple story, and on one level it certainly is. But in its simplicity it becomes one of the great westerns because it has single vision, a particular point of view, and expresses it perfectly.

4 stars out of 4.

(Originally written in 2004)

I rediscovered this film recently and curiously, have been watching it a lot at bedtime as a way to relax and go to sleep. Not that the film is sleep inducing — it just has a nice familiar 1959 feel that makes me feel comfortable.

What amazes me is that I have watched this film over an over for the past few months and never seem to tire of it. Don’t know of any other western like that. This is a film that, like a great piece of music, grows upon you with the second and third (OK in my case excessive 30th!) watching.

The opening segment is worth noting for its sylistic tone — reminds me of a stage play rather than a movie. While some have objected to the Martin-Nelson duet in the latter half of the film, the song “My Rifle, My Pony and Me,” is a classic piece of Americana sung by an American icon (Martin) at the height of his powers. He soars as an actor in this film and let’s us glimpse the talent that he never fully expressed in his career because he was thought of mainly as a singer.