Directed by Charles Laughton

Directed by Charles Laughton

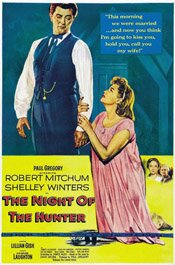

I think it’s fair to say 1955’s The Night of the Hunter is one of the oddest films to ever come out of Hollywood. According to many, it’s also one of the greatest. This may be true; I’m not sure. But it’s definitely worth seeing a time or two to decide for yourself.

The Night of the Hunter is the one and only film directed by actor Charles Laughton (Mutiny on the Bounty, Witness for the Prosecution).

A kind of weird cross between noir and fantasy, it’s a movie he described as “a nightmarish sort of Mother Goose tale.”

That’s a pretty accurate description. A frightening film, it’s characterized by a fable-myth, fantastic quality.

Robert Mitchum as Harry Powell.

A desperate man, anxious to support his impoverished family, particularly his children, kills two people while stealing $10,000. He hides the money then makes his children swear to keep the location secret from everyone.

He’s then captured, tried and convicted. Sentenced to death, he meets a preacher while in prison, prior to his execution.

During their short time together, the preacher becomes aware of the man’s theft and that the money is hidden. But he doesn’t know where.

He does, however, know it has something to do with the man’s family. He leaves the prison then goes out seeking them and the money.

Billy Chapin as the boy, John Harper. The preacher’s presence looms over the children throughout the movie.

But he’s not a genuine preacher. He is evil; twisted and murderously misogynist. (And he’s portrayed brilliantly by Robert Mitchum.) On the fingers of each hand the words are printed, “love” and “hate” (one word on each hand).

It’s interesting how the film shows that part of his dysfunction is manifested through an angry, repressed sexuality that evokes an extreme Puritanism about sex.

As the movie progresses, he becomes increasingly threatening to the children, the older child of which has been skeptical of the him from the start.

Again interesting, the film seems to associate a healthy sexuality with innocence, such as in their mother’s initial relationship with the preacher and later with another young girl-woman, Ruby.

Shelley Winters as Willa Harper comes to a bad end.

In fact, the film appears to be about the corruption of innocence, or at least the attempt to do so. While the children embody this innocence it is by no means exclusive to them. Some of the adults (like the mother, or Ruby who is on the verge of womanhood) also have some of this innocence.

Despite its noir-ish storyline and look, the movie keeps weaving into the fantastic.

It has a bit of the look and feel of Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast, 1946 (La belle et la bête), or Children of Paradise, 1945 (Les enfants du paradis), by Marcel Carné. It works as an allegory of good and evil.

Each time the story begins to take on a sense of realism of any sort, each time it begins following a traditional Hollywood film narrative approach, it swings back into this fantastic realm.

The children in their boat on the river.

For instance, there is the sequence when the children flee the preacher and set off in a boat on the river. Once on the river, the look alters to something more fantastic and starry, evoking the film’s strange opening.

This is also a movie about very strong, deliberately self-conscious imagery. From that strange, starry opening to the shots of the preacher’s tattooed hands to the river sequence with it’s shots of nature (i.e., frogs etc.) and to the shadowy shots of Mitchum in his hat, Laughton and cinematographer Stanley Cortez have carefully informed the movie with intriguing, meaningful shots.

While he only directed one movie, Charles Laughton made it a dandy. Is it one of the greatest American films ever made, as Roger Ebert says? I don’t know. But if it isn’t, it’s damn close.