Ridley Scott likes his movies big. In 2005, he made one of them — an old school sword-and-sandals epic called Kingdom of Heaven that despite its action scenes and moments of brutal violence, is overall a surprisingly quiet, thoughtful cautionary tale about the hazards of extremes.

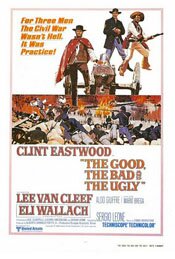

Sergio Leone and a good, odd western

I’m currently reading Marc Eliot’s Clint Eastwood: American Rebel and it inevitably got me thinking about the earlier Eastwood movies, the spaghetti westerns, including The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Below is my lengthy rambling about it from quite a while ago (2000?). For what it is worth …

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Directed by Sergio Leone

One of the best, and oddest, westerns ever made is The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo). It’s hard to imagine anyone making a movie like this today. It’s too long (it would be argued). Some of the scenes, even shots, are too long. Gee, it takes 30 minutes to introduce the three primary characters. What’s that about?

Continue reading

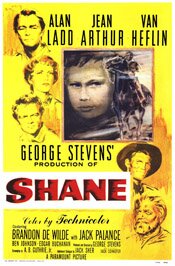

Is Shane too aware of itself as a western?

I wrote the bit below about 8 to 10 years ago after seeing Shane for the first time. It’s strictly a gut response and an attempt to figure out that gut response. But I think it may be time for me to re-watch this movie and see if I still have the same reaction or if I can finally see what many others see in the movie.

Shane (1953)

Shane (1953)

Directed by George Stevens

I’ve never seen Shane before. I haven’t discussed it in a film studies class. I haven’t spent hours in bars or cafes talking about it. I just like westerns, knew it was considered one of the best, and finally decided to watch it. So my reaction to it is, in many ways, fresh and not particularly tainted by what others think of it.

Gut response? I was a bit bored. But I’m not so sure it’s a fault of the movie so much as it’s a problem that the film’s sensibilities are of a time when they were not as frenetic as they are now. People were a bit more open to a more leisurely pace.

On the other hand, some of the problems were not just sensibility and the film’s tempo. Shane suffers, I think, from being a little too self-conscious. It’s a little too aware of the western genre, of its place in it, and of its purpose, which is too comment on the genre and film violence.

Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time.

Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time.

Shane arrives at a Wyoming homestead as a drifter. He stays for a while with people who are oppressed by cattlemen trying to take over their land. He is distant but suggests strength. Men and women admire and respect him, children hero-worship him. Eventually troubles with the cattlemen come to a head and it is Shane who faces them down.

Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence.

Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence.

The result is a lot of time spent on creating the non-violent world represented by Marion (Jean Arthur) and her husband-farmer played by Van Heflin. (He, by the way, is absolutely perfect in this role; his performance is nothing less than great.)

Unfortunately, the family life, the life of hard work, is not particularly interesting. To appreciate the value of this kind of life you have to live it. To watch it is to go to sleep.

We get to see Shane watching this life, and see his longing for it (an essential element in the film) but again, it’s a bit of a snooze. It’s one of the hardest tasks an artist can set him or herself: to make the lives of nice people interesting for an audience. It is seldom done successfully.

Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained.

Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained.

This is all just gut reaction but I really think Shane falls short primarily for one reason: it’s a movie for the intellect and not for the gonads. Westerns are meat-and-potatoes films. They are best when they’re simple. They’re best when they follow formulas. They are best when they tell you things that are true viscerally, not via the brain.

(Note: This review was written back around 2003. It was my initial response to my first viewing of the movie.)