I was very pleasantly surprised last night when I watched The Stranger, a movie I hadn’t seen before and knew little about, and found it wonderful. Apparently the director didn’t feel the same way, however, or so I’ve read.

The Stranger (1946)

Orson Welles’, The Stranger is an enthralling noir that has received some pretty shabby treatment over the years, not the least of which is by Welles himself. (Of his movies, it is the one he liked least.)

For most, it seems the movie’s biggest detraction is that it is not Citizen Kane or The Magnificent Ambersons.

For Welles, it seems the movie’s largest problem is that it is his most commercial, the movie he was forced to make to prove he could make a successful movie.

In other words, it tends to be evaluated in a debilitating context. For me, this is a great, if lesser Welles film, one I loved, and perhaps the reason I like it is that is commercial. It is constrained as far as what he could do (as if someone said, “Forget art; make something that sells!”). Maybe it works as well as it does because Welles can’t overly indulge himself.

I don’t know; I can only guess. But I do know it works better than most noirs; better than most movies, period.

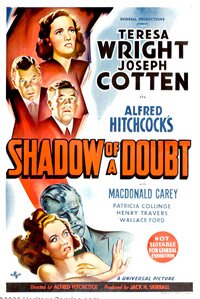

Made not long after the end of World War II, The Stranger uses a scenario that is similar to Shadow of a Doubt (1943). It is about evil living – hiding, actually – in the heart of America.

Edward G. Robinson is Wilson, a man hunting down former Nazis and bringing them to justice. Orson Welles is Professor Charles Rankin – the Nazi Franz Kindler, disguised and hiding in small town Connecticut. Loretta Young is Mary, the young woman Rankin is about to marry, someone like everyone else in the town, completely unaware of her fiancé’s past.

Of course, being an Orson Welles movie it isn’t enough that Kindler be a Nazi. He’s portrayed as the Nazi, after Hitler. He wasn’t just part of running a concentration camp; he conceived and designed them.

In order to find Kindler, a man no one can identify visually, Robinson’s Wilson arranges for another Nazi to escape prison – Meinike, a former commandant of a concentration camp – in the hope that he will lead Wilson to Kindler.

I think what most struck me about The Stranger was the degree to which the constraints placed upon Welles appear to help the movie.

It has all the expected Welles’ elements from the off-kilter camera angles, the shadows, and elongated perspectives – even imagery with meaning (such as the clock). Yet it is such a taut movie. It doesn’t flag for a moment.

It may be that the noir style helped Welles as far as achieving coherence. Or perhaps it was the imposition of those constraints and the need to show he could make something that would sell. (Theatrically, The Stranger was Welles’ most successful movie.)

Whatever the reasons, this may be Welles’ best movie from a purely entertainment perspective.