The Final Day of For the Love of Film (Noir) — Please or use the button on the right. If you’ve considered it but have put it off, now is the time. If you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down the page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

Best known as an actor, Dennis Hopper also directed movies — eight, I believe, including the well known Easy Rider. Hopper never set the world alight as a director, but in 1990 he made a pretty good film noir called The Hot Spot. (The movie’s poster does a bit of over-selling with the words, “Film noir like you’ve never seen.”)

It’s a good example of a certain kind of neo-noir. As a genre, noir returns again and again because it tells a certain kind of story in a certain way. In The Hot Spot, you sense this is why Hopper is doing a film noir. On the other hand, you can see a neo-noir like the Coens’ The Man Who Wasn’t There and view a film that chooses the genre for the same reason but also for its style — in the Coen’s case, it’s a puzzling mix of homage and parody.

The Hot Spot is really just about its story: corruption. It’s not a great movie; it’s average. Still, it’s engaging and in some ways more true to noir for that reason (and what I assume was likely a comparatively small budget). It’s made as a B-movie and looks and feels like a B-movie. Here’s the review I wrote of it about ten or so years ago. ( There may be spoilers ahead, explicit and implicit.)

The Hot Spot (1990)

Directed by Dennis Hopper

“I found my level. And I’m livin’ it.”

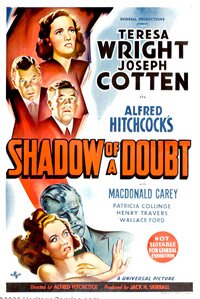

This is a pretty good film noir from 1990 directed by Dennis Hopper. For some reason The Hot Spot seems to dwell in the undeserved province of obscurity. Yet it has all the noir elements, presents them well, and resolves itself in a fashion that would please Alfred Hitchcock.

It stars Don Johnson as a drifter – we never learn much about who he is, his past, or much background to support his motivation. But this doesn’t matter; in fact, it actually works for the film since it helps create a sense of mystery.

It also leaves you never quite sure about whether he’s a good guy or a bad guy.

He wanders into a sweltering “nothing-ever-happens-here” small town to get his car repaired then takes a job as a car salesmen as he waits. While waiting, he also checks out the lay of the land. What he finds is a dull town anxious for something, anything, to happen.

It’s the tedium of the town that has generated its odor of corruption and you can’t help feeling that the catalyst behind all the avarice and moral decay is simply boredom.

While in the town, Johnson’s character sees what appears to be an easy opportunity to rob the local bank and, seeing this, he immediately begins planning to do so. Script, acting and direction work well here as it is never explicitly stated that this is what he is planning; it’s communicated through selected shots, angles, and facial expressions. In fact, while you suspect this may be what he is up to you are never quite sure.

The other two principle characters in the film are Virginia Madsen as a slatternly, greedy wife and Jennifer Connelly as a young, innocent woman who is being blackmailed (despite the apparent contradiction in that).

Compounding the problems for Johnson’s character are the relationships he forms with these women. It reflects the conflict within Johnson’s character between doing what is right and doing what is wrong: in Madsen, he recognizes a similarly corrupt soul and while he is attracted to her he is also repelled. It is as if he sees himself in her and it generates a kind of self-contempt that he expresses through his contempt of her.

In Connelly’s character, he sees what he has lost and wants to get back: a sense of innocence and goodness. Through her, he sees the man he would like to be (as opposed to Madsen’s character which shows him what he feels he is and wants to leave behind). This is the essential conflict in the story, a moral one. It drives the story. Which way will Johnson’s character ultimately go?

The story and Hopper’s directing lay a seamy, sultry tone over the entire film. It is sexy in a sluttish way; an air of corruption hangs over everything. With the exception of Connelly’s character, everyone is an aspect of moral decay. Everyone is motivated by base interests, even Johnson’s character though he is the only one struggling with it.

While not stylish in the way the Coen’s The Man Who Wasn’t There is, The Hot Spot is probably a better example of noir. (This doesn’t mean it is a better movie; just a better example.) It is better in the sense that where the noir feeling in the Coen’s film is communicated through angles, lighting and other technical and stylistic elements, in Hopper’s film it is the story, characters and performance that make this noir. It’s not a brilliant film by any means, but it is damn good. Where a movie like The Man Who Wasn’t There looks like film noir, The Hot Spot feels noir – and that is what noir is. Feeling. Mood.

If I have a quibble with the movie it would be it’s length. It probably should have trimmed about 20 or 30 minutes. After all, most of the film noirs that originated the genre ran between 70 and 90 minutes.

(By the way, there are no points for the movie’s title. It’s pretty unimaginative. It’s also the same title I Wake Up Screaming would have had if the studios had had their way. Fortunately, the actors objected and they went with the original title.)