Among the many fascinating and, in this case, amazing things about The Maltese Falcon is that it was the first film for Sydney Greenstreet who was 62 years old at the time. Can you imagine any actor today getting a role, much less starting a career at 62?

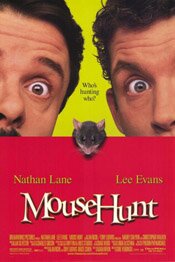

Loving and hating Mouse Hunt

Mousehunt (1997) is a funny movie in both senses of the word. It is funny “ha ha,” and it is funny peculiar.

Mousehunt (1997) is a funny movie in both senses of the word. It is funny “ha ha,” and it is funny peculiar.

For me, it is one of the funniest movies I’ve seen. Ever. I can’t think of many movies, if any, that have made me laugh out loud like this one does.

Other people, however, either like it as I do or absolutely hate it. There is no middle ground. I don’t think I’ve met anyone that felt it was “okay” or “not that good.”

They love it. Or, they hate it.

I suspect it is because the humour is so broad and slapstick. Though there is also some very funny dialogue, it is very visual humour. To an extent, it could be compared to the Three Stooges — at least as far as the visual jokes go.

Oddly, though I love Mousehunt I’ve never been a big fan of the Stooges.

Nathan Lane and Lee Evans are two brothers, Ernie and Lars Smuntz. They inherit a dilapidated house when their father dies along with a string factory that desperately needs modernization. The brothers don’t always agree. One reason is that Lars is simple and kind, for the most part, whereas Ernie is cynical and self-centred.

It’s decided (thanks to Ernie) that they will fix the house up, at least superficially, and then sell it quickly to get whatever they can for it. Then they find out it has historical significance — it’s “the missing Larue,” designed by a famous architect — and worth boatloads of money. They’re thrilled, however …

There is a mouse living in the house and it has other ideas.

As Ernie says later in the movie, after numerous painful attempts to get rid of the mouse, “He’s Hitler with a tail. He’s “The Omen” with whiskers. Even Nostradamus didn’t see him coming!”

The movie builds from one attempt to another, each more elaborate, each with a more disastrous result. There is one sequence when the brothers bring in ‘Caeser, the Exterminator’ (Christopher Walken) to rid the house of the mouse that is hilarious. Walken gives wonderfully oddball performance as Caesar.

But it’s Lee Evans as Lars that really stands out for me. Tall and gangly, he contorts his body amazingly as he delivers the slapstick humour in a brilliantly visual fashion. Onscreen, he and Nathan Lane make for a tremendous comedy team.

The movie also has a Tim Burton-like look to it; there is a distorted (as in alternately distended and extended), cartoon-ish feel to some of the sets, some camera angles and certain action sequences. The humour is not Tim Burton-like, however. It’s much more direct. It makes no effort at subtlety. That may be why it works so well.

Mousehunt was the first full length movie directed by Gore Verbinski, best known now for his Pirates of the Caribbean movies. He has also directed The Mexican (2001) and The Weather Man (2005). Though quite different movies (especially Weather Man) it strikes me that humour is a key element running through his films and of those he experiments with in the sense that Mousehunt is slapstick, Weather Man satire of a dark variety, and Pirates somewhere between.

Whatever the case, I think it’s safe to say you’ll either love or hate Mousehunt. You have to watch it first, however, to find out which.

Film noir means B-movies like The Hot Spot

The Final Day of For the Love of Film (Noir) — Please or use the button on the right. If you’ve considered it but have put it off, now is the time. If you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down the page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

Best known as an actor, Dennis Hopper also directed movies — eight, I believe, including the well known Easy Rider. Hopper never set the world alight as a director, but in 1990 he made a pretty good film noir called The Hot Spot. (The movie’s poster does a bit of over-selling with the words, “Film noir like you’ve never seen.”)

It’s a good example of a certain kind of neo-noir. As a genre, noir returns again and again because it tells a certain kind of story in a certain way. In The Hot Spot, you sense this is why Hopper is doing a film noir. On the other hand, you can see a neo-noir like the Coens’ The Man Who Wasn’t There and view a film that chooses the genre for the same reason but also for its style — in the Coen’s case, it’s a puzzling mix of homage and parody.

The Hot Spot is really just about its story: corruption. It’s not a great movie; it’s average. Still, it’s engaging and in some ways more true to noir for that reason (and what I assume was likely a comparatively small budget). It’s made as a B-movie and looks and feels like a B-movie. Here’s the review I wrote of it about ten or so years ago. ( There may be spoilers ahead, explicit and implicit.)

The Hot Spot (1990)

Directed by Dennis Hopper

“I found my level. And I’m livin’ it.”

This is a pretty good film noir from 1990 directed by Dennis Hopper. For some reason The Hot Spot seems to dwell in the undeserved province of obscurity. Yet it has all the noir elements, presents them well, and resolves itself in a fashion that would please Alfred Hitchcock.

It stars Don Johnson as a drifter – we never learn much about who he is, his past, or much background to support his motivation. But this doesn’t matter; in fact, it actually works for the film since it helps create a sense of mystery.

It also leaves you never quite sure about whether he’s a good guy or a bad guy.

He wanders into a sweltering “nothing-ever-happens-here” small town to get his car repaired then takes a job as a car salesmen as he waits. While waiting, he also checks out the lay of the land. What he finds is a dull town anxious for something, anything, to happen.

It’s the tedium of the town that has generated its odor of corruption and you can’t help feeling that the catalyst behind all the avarice and moral decay is simply boredom.

While in the town, Johnson’s character sees what appears to be an easy opportunity to rob the local bank and, seeing this, he immediately begins planning to do so. Script, acting and direction work well here as it is never explicitly stated that this is what he is planning; it’s communicated through selected shots, angles, and facial expressions. In fact, while you suspect this may be what he is up to you are never quite sure.

The other two principle characters in the film are Virginia Madsen as a slatternly, greedy wife and Jennifer Connelly as a young, innocent woman who is being blackmailed (despite the apparent contradiction in that).

Compounding the problems for Johnson’s character are the relationships he forms with these women. It reflects the conflict within Johnson’s character between doing what is right and doing what is wrong: in Madsen, he recognizes a similarly corrupt soul and while he is attracted to her he is also repelled. It is as if he sees himself in her and it generates a kind of self-contempt that he expresses through his contempt of her.

In Connelly’s character, he sees what he has lost and wants to get back: a sense of innocence and goodness. Through her, he sees the man he would like to be (as opposed to Madsen’s character which shows him what he feels he is and wants to leave behind). This is the essential conflict in the story, a moral one. It drives the story. Which way will Johnson’s character ultimately go?

The story and Hopper’s directing lay a seamy, sultry tone over the entire film. It is sexy in a sluttish way; an air of corruption hangs over everything. With the exception of Connelly’s character, everyone is an aspect of moral decay. Everyone is motivated by base interests, even Johnson’s character though he is the only one struggling with it.

While not stylish in the way the Coen’s The Man Who Wasn’t There is, The Hot Spot is probably a better example of noir. (This doesn’t mean it is a better movie; just a better example.) It is better in the sense that where the noir feeling in the Coen’s film is communicated through angles, lighting and other technical and stylistic elements, in Hopper’s film it is the story, characters and performance that make this noir. It’s not a brilliant film by any means, but it is damn good. Where a movie like The Man Who Wasn’t There looks like film noir, The Hot Spot feels noir – and that is what noir is. Feeling. Mood.

If I have a quibble with the movie it would be it’s length. It probably should have trimmed about 20 or 30 minutes. After all, most of the film noirs that originated the genre ran between 70 and 90 minutes.

(By the way, there are no points for the movie’s title. It’s pretty unimaginative. It’s also the same title I Wake Up Screaming would have had if the studios had had their way. Fortunately, the actors objected and they went with the original title.)

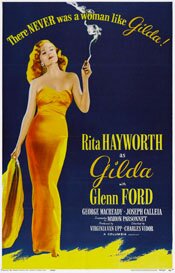

Abuse never looked as beautiful as it does in Gilda

It’s Day 7 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. We’re near the end, so now is the time to donate if you haven’t already. If you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down the page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

As much attention as Gilda gets for the beauty and sexiness of Rita Hayworth, what always strikes me is what a mean-spirited, spiteful bastard Glenn Ford is as Johnny Farrell. For about ninety percent of the movie he is abusive and hateful.

Being on the receiving end of it all, Hayworth’s Gilda is a beautiful cry for help. Intentional or not, this movie is a portrait of abuse: verbal, psychological and physical.

Gilda (1946)

Gilda (1946)

Directed by Charles Vidor

The opening of Gilda may be the perfect image for film noir. The camera tilts up from ground level revealing Glenn Ford as Johnny Farrell. He is on his hands and knees, disheveled, hair hanging down over his eyes, as he determinedly rolls his dice.The camera angle makes those dice look huge.

It is almost as if Ford is on the ground groveling.

Compare that to all the heroic shots of John Wayne in those innumerable westerns. Noir and westerns are two sides of one coin, the hero. Being noir, however, the hero must have his femme fatale to muddle up the works for him.

Inevitably, we soon encounter Rita Hayworth as Gilda.

What we soon learn about Johnny and Gilda is that they are really just small time people scrambling to make it in a less than friendly world. Neither really has any admirable characteristics, at least not through most of the movie. (At one point Gilda says, “If I’d been a ranch, they would have called me the Bar Nothing.”)

Yet somehow, for some reason, we’re on their side. Maybe it’s because in the world they inhabit they are slightly better than the other characters and we side with them because we identify with the struggles and compromises made to live in the world.

I’m always fascinated by the dichotomy of westerns and noirs and the idea that they are one thing seen from opposing angles.

When we first meet Gilda she appears like a jack-in-the-box. Her head pops up in such a way that we can’t help but see the lush and luxurious hair and the smile that seems to suggest so much, like playful sex. Everything about Gilda is sex.

For her, it’s both weakness and strength.

We also know immediately, from Johnny’s reaction to Gilda, that “something’s going on there.” They know one another; there is a relationship between them, one that has clearly soured.

The movie is also about relationships that are off in some way. There is anger, even outright hate between Johnny and Gilda, especially on Johnny’s part. As much of a weasel he was in the film’s beginning (and still is, though he has cleaned up his act), he is equally unforgiving. Gilda, encountering his spite, responds in kind.

What we’re not quite sure of is the why of it all. (I don’t recall if this is ever explained other than the fact that Johnny left her, though reasons may be suggested.)

Perhaps what is really askew between Johnny and Gilda is that neither knows what they want. Johnny wants money and power, though I imagine he would be hard pressed to answer why (beyond getting out of the gutter). It seems to be a deflective desire, something pursued in order to forget.

Gilda, on the other hand, hasn’t a clue what she wants. She is entirely reactive – to Johnny’s hate, to the men that use her, to her lack of purpose. (However she, as opposed to Johnny, begins to have an idea as the movie progresses.)

We, on the other hand, pretty much know what both want but won’t admit to themselves: each other. They live in a world of denial; neither wants to articulate the truth about their feelings.

Then there is Ballin Mundson (George Macready). Some argue there is a homoerotic element to Gilda in the relationship between Mundson and Johnny.

Given when the film was made and the shadow of the Hays Code, it would have been difficult to make something like that obvious so, initially, the argument may seem a bit of a stretch.

But the more you think about the movie the more it makes sense. Much of what happens in the film’s first half seems unlikely and arbitrary unless you see a homosexual element to it. One of the things that first struck me was how absurdly convenient it was that Johnny, in a shady part of town, is rescued from thieves by a wealthy man who just happened to be in that end of town. It makes sense, however, if he is in that part of town looking to pick someone up for sex.

The relationship that develops between Johnny and Mundson makes more sense in this context.

Johnny’s taken into Mundson’s world, given a position of authority and trust, becomes his right hand man, given access to Mundson’s wealth (including the safe) … And it all happens very quickly.

It all seems a little too convenient unless you consider there is something like a gay relationship between the two (though not a healthy gay relationship). It gains credibility if you see the relationship of Johnny to Mundson as similar to Sunset Boulevard‘s Joe Gillis to Norma Desmond.

It also adds another element to Johnny’s dislike of Gilda: there is a previous relationship between them but there is also the fact that, with Gilda as Mundson’s new wife, she is intruding on Johnny’s position.

Though it may be a bit of a long shot as far as interpretations go, I like to think that homoerotic aspect is there. It helps make sense of what are otherwise puzzling story elements and also adds a nice bit of irony in that it is present in a movie known for its heterosexual quality, the “love goddess” Rita Hayworth, famous for making heterosexual men crazy with longing.

When you get past the glitz and spectacle of Rita Hayworth’s famous sultry sexuality in the movie, the more you can’t help thinking this is one crazy movie about abuse and aberrant psychology. And you know, despite the happy gloss of the ending, that it will continue. Johnny and Gilda may have mended their fences and be doe-eyed once again, but the abuse will be back.

(Note: Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford would be teamed again six years later in 1952’s Affair in Trinidad, an attempt to jump start Rita’s career and a poor knock off of Gilda.)