It’s Day 7 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. We’re near the end, so now is the time to donate if you haven’t already. If you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down the page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

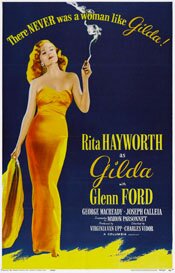

As much attention as Gilda gets for the beauty and sexiness of Rita Hayworth, what always strikes me is what a mean-spirited, spiteful bastard Glenn Ford is as Johnny Farrell. For about ninety percent of the movie he is abusive and hateful.

Being on the receiving end of it all, Hayworth’s Gilda is a beautiful cry for help. Intentional or not, this movie is a portrait of abuse: verbal, psychological and physical.

Gilda (1946)

Gilda (1946)

Directed by Charles Vidor

The opening of Gilda may be the perfect image for film noir. The camera tilts up from ground level revealing Glenn Ford as Johnny Farrell. He is on his hands and knees, disheveled, hair hanging down over his eyes, as he determinedly rolls his dice.The camera angle makes those dice look huge.

It is almost as if Ford is on the ground groveling.

Compare that to all the heroic shots of John Wayne in those innumerable westerns. Noir and westerns are two sides of one coin, the hero. Being noir, however, the hero must have his femme fatale to muddle up the works for him.

Inevitably, we soon encounter Rita Hayworth as Gilda.

What we soon learn about Johnny and Gilda is that they are really just small time people scrambling to make it in a less than friendly world. Neither really has any admirable characteristics, at least not through most of the movie. (At one point Gilda says, “If I’d been a ranch, they would have called me the Bar Nothing.”)

Yet somehow, for some reason, we’re on their side. Maybe it’s because in the world they inhabit they are slightly better than the other characters and we side with them because we identify with the struggles and compromises made to live in the world.

I’m always fascinated by the dichotomy of westerns and noirs and the idea that they are one thing seen from opposing angles.

When we first meet Gilda she appears like a jack-in-the-box. Her head pops up in such a way that we can’t help but see the lush and luxurious hair and the smile that seems to suggest so much, like playful sex. Everything about Gilda is sex.

For her, it’s both weakness and strength.

We also know immediately, from Johnny’s reaction to Gilda, that “something’s going on there.” They know one another; there is a relationship between them, one that has clearly soured.

The movie is also about relationships that are off in some way. There is anger, even outright hate between Johnny and Gilda, especially on Johnny’s part. As much of a weasel he was in the film’s beginning (and still is, though he has cleaned up his act), he is equally unforgiving. Gilda, encountering his spite, responds in kind.

What we’re not quite sure of is the why of it all. (I don’t recall if this is ever explained other than the fact that Johnny left her, though reasons may be suggested.)

Perhaps what is really askew between Johnny and Gilda is that neither knows what they want. Johnny wants money and power, though I imagine he would be hard pressed to answer why (beyond getting out of the gutter). It seems to be a deflective desire, something pursued in order to forget.

Gilda, on the other hand, hasn’t a clue what she wants. She is entirely reactive – to Johnny’s hate, to the men that use her, to her lack of purpose. (However she, as opposed to Johnny, begins to have an idea as the movie progresses.)

We, on the other hand, pretty much know what both want but won’t admit to themselves: each other. They live in a world of denial; neither wants to articulate the truth about their feelings.

Then there is Ballin Mundson (George Macready). Some argue there is a homoerotic element to Gilda in the relationship between Mundson and Johnny.

Given when the film was made and the shadow of the Hays Code, it would have been difficult to make something like that obvious so, initially, the argument may seem a bit of a stretch.

But the more you think about the movie the more it makes sense. Much of what happens in the film’s first half seems unlikely and arbitrary unless you see a homosexual element to it. One of the things that first struck me was how absurdly convenient it was that Johnny, in a shady part of town, is rescued from thieves by a wealthy man who just happened to be in that end of town. It makes sense, however, if he is in that part of town looking to pick someone up for sex.

The relationship that develops between Johnny and Mundson makes more sense in this context.

Johnny’s taken into Mundson’s world, given a position of authority and trust, becomes his right hand man, given access to Mundson’s wealth (including the safe) … And it all happens very quickly.

It all seems a little too convenient unless you consider there is something like a gay relationship between the two (though not a healthy gay relationship). It gains credibility if you see the relationship of Johnny to Mundson as similar to Sunset Boulevard‘s Joe Gillis to Norma Desmond.

It also adds another element to Johnny’s dislike of Gilda: there is a previous relationship between them but there is also the fact that, with Gilda as Mundson’s new wife, she is intruding on Johnny’s position.

Though it may be a bit of a long shot as far as interpretations go, I like to think that homoerotic aspect is there. It helps make sense of what are otherwise puzzling story elements and also adds a nice bit of irony in that it is present in a movie known for its heterosexual quality, the “love goddess” Rita Hayworth, famous for making heterosexual men crazy with longing.

When you get past the glitz and spectacle of Rita Hayworth’s famous sultry sexuality in the movie, the more you can’t help thinking this is one crazy movie about abuse and aberrant psychology. And you know, despite the happy gloss of the ending, that it will continue. Johnny and Gilda may have mended their fences and be doe-eyed once again, but the abuse will be back.

(Note: Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford would be teamed again six years later in 1952’s Affair in Trinidad, an attempt to jump start Rita’s career and a poor knock off of Gilda.)