Relationships, sex, communists and, somewhere off camera ,World War II — The Male Animal from 1942 is a curious film to say the least. It comes with some pretty impressive credentials, however, including its stars as well as its origins: based on a play by James Thurber and a screenplay with writers that included the Epstein brothers.

When style beats the pants off of story

Among the many fascinating and, in this case, amazing things about The Maltese Falcon is that it was the first film for Sydney Greenstreet who was 62 years old at the time. Can you imagine any actor today getting a role, much less starting a career at 62?

American Rebel: Eastwood bio a disappointing read

While I remember the song from Rawhide I don’t recall ever having seen it. For me, Clint Eastwood’s career would have begun with A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

The crazed and opulent Cleopatra

It’s appropriate that what I’ve written below about Cleopatra should be muddled as it is. That kind of reflects the movie. It’s a mess, in any number of ways, but what an arresting mess!

I’m pretty sure I saw this movie in the theatre when I was a kid and bits and pieces on TV over the years. I sat mesmerized through the entire movie about ten years ago when it came out on DVD. A week or so ago, however, I watched it again but this time it took me three days — I kept falling asleep on the couch. I suspect that was due to three things: 1) having seen it a few times already, 2) the sheer length of the movie and, 3) more wine than was wise.

As movies go, Cleopatra isn’t good or bad; it’s okay. But it’s probably the most fascinating “okay” movie you can see.

Continue reading

Crawford and Gable and the oddball Strange Cargo

I stumbled upon Strange Cargo last night and rarely has the word “strange” in a title been used so appropriately. This movie is strange indeed. It’s also a pretty good adventure film starring Joan Crawford and Clark Gable (the latter’s previous movie was Gone With the Wind).

Strange Cargo (1940)

Strange Cargo (1940)

Directed by Frank Borzage

Crawford and Gable are two feisty lovers with a stormy relationship. Neither is a person of outstanding character. The storminess was likely easy for both to convey because in reality the pair, who had a prior relationship, detested one another.

In the movie, Crawford is essentially a hooker (though Hollywood censorship of the period means this is only vaguely suggested). Gable is a nasty, self-centered rogue who manages to be charming at the same time.

We find them on Devil’s Island (French Guiana) where they get mixed up with a group of convicts in an escape attempt. The majority of the movie is the struggles and conflicts of this rag tag bunch as they make their way through the jungle and swamps of the island and then on board a small ship as they try to get away.

Fine enough, and a pretty de rigueur setting for an adventure of the period. But there is an element in the movie that makes it anything but de rigueur. That element is the character of Cambreau, played by Ian Hunter. He appears mysteriously and joins the convicts in their escape but he is not your usual prisoner.

Cambreau is a Christ-like figure that steers the movie into religious allegory and allows the film to meditate on subjects like God, morality, ethics and honour. While this may not sound appealing (and yes, occasionally it is a little heavy-handed), the mysterious quality Hunter’s Cambreau figure brings adds to the adventure.

Gable, by the way, objected to this aspect of the movie. He thought it would prompt audiences to stay away. In his opinion, people expected love and sex in a Crawford-Gable movie.

Both Crawford and Gable are wonderful in the movie, particularly Crawford as the slatternly Julie. I read somewhere that Crawford was quite proud of the way she put her “star” image aside and portrayed the character. I noticed how in many scenes she adds small, subtle touches to communicate the character’s “low rent” status, such as one scene where it is in how she sits (not what my mother would have called “lady-like”.)

She also went without makeup or false eyelashes and her costume, essentially two dresses, was from a bargain boutique.

Gable is equally unglamorous in his appearance, wearing torn clothes and growing increasingly unshaven as the movie progresses. In fact, the movie appears to make a concerted effort to ensure both its stars are unstar-like, visually.

The end result is a movie that is peculiar yet compelling, partly due to its oddness. The Cambreau character, while bringing in the religious element, also adds mystery to the overall adventure as no one ever quite knows who he is.

On the other hand, some scenes aren’t subtle in communicating the Christ figure aspect, such as the scene near the end when Cambreau is in the stormy waters with his arms out, as if on a cross.

Yes, Strange Cargo is an odd movie. But it’s worth seeing at least once, especially if you’re a Gable or Crawford fan.

An aside … According to Warren Harris in Clark Gable: A Biography, this movie was made at a time when “Joan Crawford, whose box-office popularity had sunk an all-time low, had talked L.B. Mayer into teaming them (Gable and Crawford) for the first time since the 1936 Love On the Run, which was also Crawford’s last hit.”

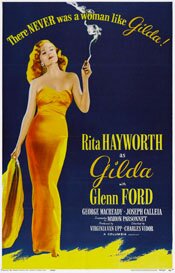

Abuse never looked as beautiful as it does in Gilda

It’s Day 7 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. We’re near the end, so now is the time to donate if you haven’t already. If you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down the page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

As much attention as Gilda gets for the beauty and sexiness of Rita Hayworth, what always strikes me is what a mean-spirited, spiteful bastard Glenn Ford is as Johnny Farrell. For about ninety percent of the movie he is abusive and hateful.

Being on the receiving end of it all, Hayworth’s Gilda is a beautiful cry for help. Intentional or not, this movie is a portrait of abuse: verbal, psychological and physical.

Gilda (1946)

Gilda (1946)

Directed by Charles Vidor

The opening of Gilda may be the perfect image for film noir. The camera tilts up from ground level revealing Glenn Ford as Johnny Farrell. He is on his hands and knees, disheveled, hair hanging down over his eyes, as he determinedly rolls his dice.The camera angle makes those dice look huge.

It is almost as if Ford is on the ground groveling.

Compare that to all the heroic shots of John Wayne in those innumerable westerns. Noir and westerns are two sides of one coin, the hero. Being noir, however, the hero must have his femme fatale to muddle up the works for him.

Inevitably, we soon encounter Rita Hayworth as Gilda.

What we soon learn about Johnny and Gilda is that they are really just small time people scrambling to make it in a less than friendly world. Neither really has any admirable characteristics, at least not through most of the movie. (At one point Gilda says, “If I’d been a ranch, they would have called me the Bar Nothing.”)

Yet somehow, for some reason, we’re on their side. Maybe it’s because in the world they inhabit they are slightly better than the other characters and we side with them because we identify with the struggles and compromises made to live in the world.

I’m always fascinated by the dichotomy of westerns and noirs and the idea that they are one thing seen from opposing angles.

When we first meet Gilda she appears like a jack-in-the-box. Her head pops up in such a way that we can’t help but see the lush and luxurious hair and the smile that seems to suggest so much, like playful sex. Everything about Gilda is sex.

For her, it’s both weakness and strength.

We also know immediately, from Johnny’s reaction to Gilda, that “something’s going on there.” They know one another; there is a relationship between them, one that has clearly soured.

The movie is also about relationships that are off in some way. There is anger, even outright hate between Johnny and Gilda, especially on Johnny’s part. As much of a weasel he was in the film’s beginning (and still is, though he has cleaned up his act), he is equally unforgiving. Gilda, encountering his spite, responds in kind.

What we’re not quite sure of is the why of it all. (I don’t recall if this is ever explained other than the fact that Johnny left her, though reasons may be suggested.)

Perhaps what is really askew between Johnny and Gilda is that neither knows what they want. Johnny wants money and power, though I imagine he would be hard pressed to answer why (beyond getting out of the gutter). It seems to be a deflective desire, something pursued in order to forget.

Gilda, on the other hand, hasn’t a clue what she wants. She is entirely reactive – to Johnny’s hate, to the men that use her, to her lack of purpose. (However she, as opposed to Johnny, begins to have an idea as the movie progresses.)

We, on the other hand, pretty much know what both want but won’t admit to themselves: each other. They live in a world of denial; neither wants to articulate the truth about their feelings.

Then there is Ballin Mundson (George Macready). Some argue there is a homoerotic element to Gilda in the relationship between Mundson and Johnny.

Given when the film was made and the shadow of the Hays Code, it would have been difficult to make something like that obvious so, initially, the argument may seem a bit of a stretch.

But the more you think about the movie the more it makes sense. Much of what happens in the film’s first half seems unlikely and arbitrary unless you see a homosexual element to it. One of the things that first struck me was how absurdly convenient it was that Johnny, in a shady part of town, is rescued from thieves by a wealthy man who just happened to be in that end of town. It makes sense, however, if he is in that part of town looking to pick someone up for sex.

The relationship that develops between Johnny and Mundson makes more sense in this context.

Johnny’s taken into Mundson’s world, given a position of authority and trust, becomes his right hand man, given access to Mundson’s wealth (including the safe) … And it all happens very quickly.

It all seems a little too convenient unless you consider there is something like a gay relationship between the two (though not a healthy gay relationship). It gains credibility if you see the relationship of Johnny to Mundson as similar to Sunset Boulevard‘s Joe Gillis to Norma Desmond.

It also adds another element to Johnny’s dislike of Gilda: there is a previous relationship between them but there is also the fact that, with Gilda as Mundson’s new wife, she is intruding on Johnny’s position.

Though it may be a bit of a long shot as far as interpretations go, I like to think that homoerotic aspect is there. It helps make sense of what are otherwise puzzling story elements and also adds a nice bit of irony in that it is present in a movie known for its heterosexual quality, the “love goddess” Rita Hayworth, famous for making heterosexual men crazy with longing.

When you get past the glitz and spectacle of Rita Hayworth’s famous sultry sexuality in the movie, the more you can’t help thinking this is one crazy movie about abuse and aberrant psychology. And you know, despite the happy gloss of the ending, that it will continue. Johnny and Gilda may have mended their fences and be doe-eyed once again, but the abuse will be back.

(Note: Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford would be teamed again six years later in 1952’s Affair in Trinidad, an attempt to jump start Rita’s career and a poor knock off of Gilda.)

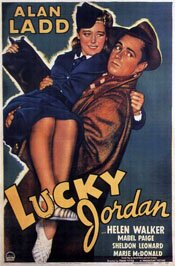

Lucky Jordan a pleasant surprise

Once again, I stumbled on a movie I wasn’t looking for or even aware of. But last night I skipped through channels and came on TCM. The movie they were showing? Lucky Jordan. (Later, they showed The Snows of Kilimanjaro, 1952, a movie I personally find incredibly tedious. But that’s personal taste …)

Lucky Jordan (1942)

Lucky Jordan (1942)

Directed by Frank Tuttle

I really wish I had been around in 1942 and been in a theatre at a screening of this movie, Lucky Jordan. I think the response to it would have been fascinating to see.

The U.S. had already endured Pearl Harbour. They had entered World War II. And here was a movie where the lead character wanted nothing to do with the military; he had nothing but disdain for it.

How did they make that fly?

Undoubtedly it helped to have Alan Ladd, who was becoming a name by this time. (He had previously done movies like This Gun For Hire. This movie, Lucky Jordan, was the first one in which he had top billing, I believe.)

Ladd plays Lucky Jordan and through well over the first half of the movie he plays a gangster with no interest or love for anyone but himself and his money. He’s a cynic and believes everything and everyone can be bought, until he comes up against the draft board.

He eventually finds himself in the Army where he is contemptuous of it. He goes AWOL and finally deserts. He comes upon secret military plans which another gangster (Sheldon Leonard as Slip Moran) has plans to sell to the Nazi’s. Slip also has plans to take over from Lucky.

He eventually finds himself in the Army where he is contemptuous of it. He goes AWOL and finally deserts. He comes upon secret military plans which another gangster (Sheldon Leonard as Slip Moran) has plans to sell to the Nazi’s. Slip also has plans to take over from Lucky.

But Lucky has other plans – get rid of Slip and sell the plans himself, but for more money.

In the process he kidnaps Jill Evans (Helen Walker), a woman in the military who pleads love of country to Lucky, but it falls on deaf ears.

The way the movie manages to turn the character of Lucky around, as eventually it must, is through an old woman living in poverty, Annie (aka ‘Ma’), played wonderfully by Mabel Paige. Annie and Lucky adopt one another, so to speak, and develop a kind of mother and son relationship. This is the first time we start to see chinks in Lucky’s cynical armor and the glimmers of a human being.

Alan Ladd plays the part of Lucky nicely. What often comes across is not hard-bitten and cynical but a sense of genuine puzzlement when his motives are questioned. Isn’t everyone out for themselves? Why would he do anything else?

The movie ends with an inevitable patriotic finish, the final scene feeling like an obligatory add-on. But in the process of getting from start to end, it tells a good story about a particular character, Lucky Jordan. In the process, it doesn’t simply use a self-centred individual. The script gives some explanation for why he is as he is by giving some detail on his background.

The movie ends with an inevitable patriotic finish, the final scene feeling like an obligatory add-on. But in the process of getting from start to end, it tells a good story about a particular character, Lucky Jordan. In the process, it doesn’t simply use a self-centred individual. The script gives some explanation for why he is as he is by giving some detail on his background.

On the whole, this movie was a very pleasant surprise. It’s a movie cranked out by the Hollywood factory but it’s also one that manages to work well within its constraints – even push them a little, given how explicitly unpatriotic and unrepentant the character of Lucky is through a large portion of the film.

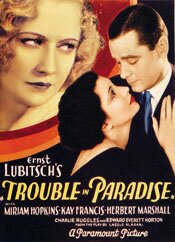

Ernst Lubitsch and his lustfully troubled Paradise

Without really planning too, I’ve found myself watching the movies of Ernst Lubitsch. A few nights ago it was The Shop Around the Corner. Last night it was Trouble in Paradise. I had seen both before, at least once each. What I find interesting is that the more I see them, the more I like them. The first time around you miss how well constructed they are because they evolve so seamlessly. So I definitely recommend seeing them at least twice.

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

One of the finest romantic comedies ever made, and one that in many ways created a template and set standards for later romantic comedies (while also looking ahead to the screwball comedies to come), is Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise, made in 1932.

With a single film, American cinema suddenly grew up. In many ways, it’s the most adult film Hollywood has ever made. (Not long after, production codes were put in place and much of what is in Trouble in Paradise would not have been allowed.)

Prior to Lubitsch’s first nonmusical American film, the sophisticated manner and style of this movie hadn’t been seen, not on this side of the Atlantic. Nor had this degree of elevated wit or sexual play.

Much is made of the “Lubitsch touch,” and there certainly is such a thing. While a bit hard to define precisely, it has a great deal to do with a European sensibility, one not informed by a Puritan cultural background. It has to do with wit and sophistication and adult romance.

Much is made of the “Lubitsch touch,” and there certainly is such a thing. While a bit hard to define precisely, it has a great deal to do with a European sensibility, one not informed by a Puritan cultural background. It has to do with wit and sophistication and adult romance.

Here, adult means playful, well-mannered and tinged by a degree of melancholy. Trouble in Paradise is a perfect example of this.

The movie is about two charming thieves, their love for one another, as well as their enjoyment of their craft. It’s about the playfulness between them, and the woman whom they choose as their mark.

Herbert Marshall is the thief Gaston Monescu. He charms his way into the life of Mariette Colet (Kay Francis) in order to steal her money. His love, the pickpocket Lily (Miriam Hopkins), is his accomplice.

But this is what Hitchcock would call the McGuffin. The movie is really about the triangle that develops as Gaston becomes romantically enchanted by Mariette just as she falls in love with him. All the while, Lily is still there and still loves Gaston, just as he still loves her.

But this is what Hitchcock would call the McGuffin. The movie is really about the triangle that develops as Gaston becomes romantically enchanted by Mariette just as she falls in love with him. All the while, Lily is still there and still loves Gaston, just as he still loves her.

Lubitsch’s direction is nothing less than wonderful here. One of the qualities that characterize his films, especially in Trouble in Paradise, is his refusal to be obvious about anything. He tells his story through indirection and implication, rarely being overt.

This is particularly true with the way he implies sexuality and its encounters without ever stating, much less showing, anything. It is part of the film’s playful wit and charm and adult quality. Equally adult is the absence of any salacious sense. There is no sense of “nudge-nudge, wink-wink” here.

Yet, essentially, the film is about lust, Gaston’s and Mariette’s.

As Peter Bogdanovich mentions in his introduction to the Criterion DVD of the film, it’s a wonder this was ever made in Hollywood, particularly when we see where we are today.

As Peter Bogdanovich mentions in his introduction to the Criterion DVD of the film, it’s a wonder this was ever made in Hollywood, particularly when we see where we are today.

While the troubled triangle of Gaston, Mariette and Lily plays out, the movie also gives us the ineffectual efforts of the Major (Charlie Ruggles) and Francois (Edward Everett Horton), two of Mariette’s luckless suitors. Their ineptness and pretensions provide a nice comedic counterpoint to the sophistication of Gaston.

Much of what Lubitsch does isn’t noticed on first viewing the movie. It is too seamless and fluid. The plot unfolds too effortlessly. It’s only on seeing a second or third or fourth time you see the small details he attends to and just how cleverly the movie is constructed.

In cinema terms, Ernst Lubitsch was a magician. Much of what he does is a kind of sleight of hand — verbal and visual. His movies, like Trouble in Paradise, are mature, charming and absolutely wonderful.

See:

Four movies and a post

Over this holiday period, while I haven’t been posting on any of my sites, neither have I been sitting still.

Over this holiday period, while I haven’t been posting on any of my sites, neither have I been sitting still.

Here on Piddleville, I actually have been adding reviews, though not highlighting them on the home page here.

I hope to rectify that today. So, recently seen …

Holiday Inn (1942)

The movie Holiday Inn is memorable for a number of things, some good, some not so good. To begin with, it brings together a trio made up of Irving Berlin, Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire. Not a bad place to start. The movie itself is a Hollywood soufflé, very light, very unlikely, and quite delightful…

Read more

Unbreakable (2002)

Movies with surprise endings don’t often work well and, even when they do, it’s easy to tire of them quickly. In a sense, they are gimmicky. Done rarely, they’re riveting; done often, they’re tedious. I think M. Night Shyamalan knows this and feels the same way … You get the sense as you watch Unbreakable that he was trying to avoid the surprise ending. On the other hand, you also get the sense that stories of that kind are his natural inclination…

Read more

The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945)

The Bells of St. Mary’s is movie that is very representative of a type of movie Hollywood made in its heyday, very much the way it’s predecessor was, Going My Way. On one hand, it is a type of film that Hollywood has continued to make (like certain Disney films) with varying degrees of success – family oriented and sentimental. On the other hand, it is anachronistic and, for some, nostalgic…

Read more

Now, Voyager (1942)

Here’s a movie that caught me by surprise. It’s another one of those films I went into with little or no expectations. In fact, if anything, I expected it to be a dud. (I had seen a number of older, black and white turkeys recently.) Now, Voyager was wonderful. It’s also an unapologetic soap opera, the kind Hollywood once did so well…

Read more

And now you are up to date. Sort of. More or less. My memory isn’t great; I may have have forgotten something …