I watched Steven Spielberg’s Catch Me If You Can yet again (third time) over the weekend and now I’m back to my original opinion (as opposed to the one expressed below). Despite being promoted as ‘fun,’ and despite the sixties style ‘fun’ animation of the title sequence, this is really a rather somber story of a young man desperate to save his father from a marriage and life that are disintegrating.

The crazed and opulent Cleopatra

It’s appropriate that what I’ve written below about Cleopatra should be muddled as it is. That kind of reflects the movie. It’s a mess, in any number of ways, but what an arresting mess!

I’m pretty sure I saw this movie in the theatre when I was a kid and bits and pieces on TV over the years. I sat mesmerized through the entire movie about ten years ago when it came out on DVD. A week or so ago, however, I watched it again but this time it took me three days — I kept falling asleep on the couch. I suspect that was due to three things: 1) having seen it a few times already, 2) the sheer length of the movie and, 3) more wine than was wise.

As movies go, Cleopatra isn’t good or bad; it’s okay. But it’s probably the most fascinating “okay” movie you can see.

Continue reading

For the Love of Film (Noir): This Gun For Hire

Today the For the Love of Film (Noir) blogathon begins and I decided rather than burble about the genre, which can be as murky as the streets and lives its films tend to articulate, I’d post something about a specific noir, one that stars an actor who really hit his stride, as far as fame goes, with the genre and this particular movie, This Gun For Hire. The actor, of course, is Alan Ladd.

The blogathon runs thru to February 21st with the goal of raising money to restore a specific movie, The Sound of Fury (1950, aka Try and Get Me). I love the brief description on IMDb, “A man down on his luck falls in with a criminal. After a senseless murder, the two are lynched.” If you’re inclined to pitch in, please do. You can . And now, on with …

This Gun For Hire (1942)

Directed by Frank Tuttle

I came upon a review of This Gun For Hire that complained about it being viewed as film noir. The reviewer argued it was not; it was pulp. The first thing I thought was, “Aren’t all the best film noirs pulp?” My second thought was a sigh because film noir is so idiosyncratic in its definition. Everyone has their own idea of what it is.

For me, this movie is film noir. Regardless of whether it is or not, the important thing is it’s a wholly captivating movie, thanks largely to Alan Ladd’s portrayal of Raven.

Of course there is also some pretty brisk direction from Frank Tuttle and a good script.

Billing aside, this is Alan Ladd’s movie. He is the star. As good as they are, you could replace Robert Preston and Veronica Lake and not much would change. Replace Ladd and I suspect you would have a different movie and perhaps not as good.

Amid the murder and mayhem of the film, it is the story of Raven: what he does and why he does it. In other words, it’s about who he is. In the first few minutes, we see a man who uses a gun and, given the title, we infer it is for nothing good.

But we quickly see him with a cat and a moment of softening. He cares for the cat; there is tenderness. Raven then leaves the room and almost immediately we see a woman come in to tidy it. She shoos the cat away crossly and Raven steps back into the room.

Now we see what the gun is about. We see the Raven the world must deal with. He strikes the woman, tears her dress and forces her out of the room.

It is less what he does than it is how he does it: quick, brutal and unrepentant. The tenderness he has for cats is not extended to people. The opening, then, tells us what we need to know about the character. From here, the story’s engine kicks in. The opening is a great example of exposition. It provides essential information, and in a riveting way, so we can understand what is to follow.

What follows is standard pulp/film noir material. Raven is a hired killer. He does a job. Then he is shafted by the man who hired him. He’s paid with marked, stolen money. As soon as he spends some of it, the police are after him and he immediately recognizes what has happened. Now his goal is simple: kill the people who set him up. And he is nothing if not focused.

It is not that simple, however. There are complications. But this is the essential story: Raven on a mission to kill the people who set him up and how his character is revealed and alters in the process. Even the ostensible stars, Preston and Lake, are secondary to Ladd’s Raven. They are tools for revealing his character.

As with the similar (though not nearly as good) movie, Lucky Jordan, the complications involve the Second World War, selling vital material to the enemy, and patriotic pleas. Raven cares only for himself (as does Jordan) and it’s the role of Lake to persuade him to see the larger picture and care for the country which means other people.

What she is up against is a man whose background was as brutal as he has become and that has defined him and how he sees the world. The world he now inhabits confirms his view. Yet we know there is something human in him from how he relates to cats and we understand later in the film why he is as he is in a scene where he describes his childhood. Despite his callousness and violence, we care about him.

Although he was in countless movies prior to this one, This Gun For Hire was the first time Alan Ladd starred in a movie, although he was sitting in the back row as far as the billing went. I can understand why he hadn’t been noticed prior to this though. From the few movies I’ve seen him in, Ladd seems one of the quietest, most understated actors I’ve seen. Few actors express anger and melancholy as well as he does or as naturally.

Frank Tuttle, a kind of journeyman director who cranked out movies for the studio, excels here, perhaps because of the script, perhaps because of the work of cinematographer John F. Seitz, or maybe because he was a meat and potatoes director. The movie is simply and quickly directed and that is one of its virtues.

Call it a crime film, call it pulp, call it what you will, to me this is a great example of noir and regardless of genre a thoroughly compelling movie. As you may have guessed, I liked it a lot.

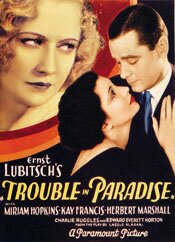

Ernst Lubitsch and his lustfully troubled Paradise

Without really planning too, I’ve found myself watching the movies of Ernst Lubitsch. A few nights ago it was The Shop Around the Corner. Last night it was Trouble in Paradise. I had seen both before, at least once each. What I find interesting is that the more I see them, the more I like them. The first time around you miss how well constructed they are because they evolve so seamlessly. So I definitely recommend seeing them at least twice.

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

One of the finest romantic comedies ever made, and one that in many ways created a template and set standards for later romantic comedies (while also looking ahead to the screwball comedies to come), is Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise, made in 1932.

With a single film, American cinema suddenly grew up. In many ways, it’s the most adult film Hollywood has ever made. (Not long after, production codes were put in place and much of what is in Trouble in Paradise would not have been allowed.)

Prior to Lubitsch’s first nonmusical American film, the sophisticated manner and style of this movie hadn’t been seen, not on this side of the Atlantic. Nor had this degree of elevated wit or sexual play.

Much is made of the “Lubitsch touch,” and there certainly is such a thing. While a bit hard to define precisely, it has a great deal to do with a European sensibility, one not informed by a Puritan cultural background. It has to do with wit and sophistication and adult romance.

Much is made of the “Lubitsch touch,” and there certainly is such a thing. While a bit hard to define precisely, it has a great deal to do with a European sensibility, one not informed by a Puritan cultural background. It has to do with wit and sophistication and adult romance.

Here, adult means playful, well-mannered and tinged by a degree of melancholy. Trouble in Paradise is a perfect example of this.

The movie is about two charming thieves, their love for one another, as well as their enjoyment of their craft. It’s about the playfulness between them, and the woman whom they choose as their mark.

Herbert Marshall is the thief Gaston Monescu. He charms his way into the life of Mariette Colet (Kay Francis) in order to steal her money. His love, the pickpocket Lily (Miriam Hopkins), is his accomplice.

But this is what Hitchcock would call the McGuffin. The movie is really about the triangle that develops as Gaston becomes romantically enchanted by Mariette just as she falls in love with him. All the while, Lily is still there and still loves Gaston, just as he still loves her.

But this is what Hitchcock would call the McGuffin. The movie is really about the triangle that develops as Gaston becomes romantically enchanted by Mariette just as she falls in love with him. All the while, Lily is still there and still loves Gaston, just as he still loves her.

Lubitsch’s direction is nothing less than wonderful here. One of the qualities that characterize his films, especially in Trouble in Paradise, is his refusal to be obvious about anything. He tells his story through indirection and implication, rarely being overt.

This is particularly true with the way he implies sexuality and its encounters without ever stating, much less showing, anything. It is part of the film’s playful wit and charm and adult quality. Equally adult is the absence of any salacious sense. There is no sense of “nudge-nudge, wink-wink” here.

Yet, essentially, the film is about lust, Gaston’s and Mariette’s.

As Peter Bogdanovich mentions in his introduction to the Criterion DVD of the film, it’s a wonder this was ever made in Hollywood, particularly when we see where we are today.

As Peter Bogdanovich mentions in his introduction to the Criterion DVD of the film, it’s a wonder this was ever made in Hollywood, particularly when we see where we are today.

While the troubled triangle of Gaston, Mariette and Lily plays out, the movie also gives us the ineffectual efforts of the Major (Charlie Ruggles) and Francois (Edward Everett Horton), two of Mariette’s luckless suitors. Their ineptness and pretensions provide a nice comedic counterpoint to the sophistication of Gaston.

Much of what Lubitsch does isn’t noticed on first viewing the movie. It is too seamless and fluid. The plot unfolds too effortlessly. It’s only on seeing a second or third or fourth time you see the small details he attends to and just how cleverly the movie is constructed.

In cinema terms, Ernst Lubitsch was a magician. Much of what he does is a kind of sleight of hand — verbal and visual. His movies, like Trouble in Paradise, are mature, charming and absolutely wonderful.

See:

Shock isn’t scary; suspense is – The Sixth Sense

As October wraps up, it seems appropriate to talk about a movie from 1999 that was a genuinely good, suspense-filled ghost story. It’s one that caught most people off guard, especially with its ending. And it was so quiet!

The Sixth Sense (1999)

Directed by M. Night Shaymalan

It’s undoubtedly due to the time of year that I find I’ve been recently watching films of a supernatural nature. Not long ago I wrote about The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947) and last week Ugetsu (1953). Those two movies tackled the subject of ghosts in very different ways. Last night I watched The Sixth Sense (1999), a movie that takes on the subject in a much more traditional way. It’s aspires to, and succeeds at, being a scary movie.

It’s undoubtedly due to the time of year that I find I’ve been recently watching films of a supernatural nature. Not long ago I wrote about The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947) and last week Ugetsu (1953). Those two movies tackled the subject of ghosts in very different ways. Last night I watched The Sixth Sense (1999), a movie that takes on the subject in a much more traditional way. It’s aspires to, and succeeds at, being a scary movie.

Most people I know have seen the movie but if you have not you should know that this entire review is likely to be a spoiler, so you’ve been warned. If you haven’t seen the film, I recommend reading nothing about it anywhere until you have.

I’ve probably seen The Sixth Sense three or four times now and each time I feel a sense of melancholy – except for that first time. I feel that way because, once seen, you can never see it as you did that first time. Once seen, it becomes a completely new movie. (See, You can’t watch the same movie twice.)

However, make no mistake. This is a movie that should be seen at least twice. In a sense, you get two movies for the price of one: the movie where you didn’t know the ending and the one where you do know how it ends. That difference is a big deal with this movie.

Haley Joel Osment plays Cole, a very troubled boy. Bruce Willis plays a child psychologist, Dr. Malcolm Crowe, who tries to help him. It isn’t until roughly the movie’s mid-point that we (and Dr. Crowe) discover the nature of Cole’s trouble: “I see dead people.”

Haley Joel Osment plays Cole, a very troubled boy. Bruce Willis plays a child psychologist, Dr. Malcolm Crowe, who tries to help him. It isn’t until roughly the movie’s mid-point that we (and Dr. Crowe) discover the nature of Cole’s trouble: “I see dead people.”

Yes, we’re in a ghost story. It’s one that ends with a big revelation for the audience (even more so for Dr. Crowe). All the tumblers fall into place then as we understand that what we’ve seen was not what we thought we were seeing.

Watching the movie again, you see how all the clues are there and most are remarkably simple, even obvious, and you wonder how you didn’t see them the first time. The answer is that writer/director M. Night Shyamalan understands how we watch movies, especially our expectations.

There is a scene in the movie where Dr. Crowe shows Cole a magic trick and it’s a nice analogy for how the movie works. His trick is no trick at all. The scene is about setting up a trick and how in setting it up we expect something. The trick (if you can call it that) is that what we expect doesn’t happen.

The movie also works because Shyamalan also understands that a scary movie is all about mood. You may notice how remarkably quiet the movie is. With the exception of a few short scenes, most of the movie is still, almost silent. When characters speak to one another it’s intimately, often whispered and hushed. Sound is used delicately and when it is loud it is usually brief and for punctuation, such as a scene where a quick, single chord is heard as a ghost passes by a door. Yes, we jump.

The performances are also very good and, because they are, help pull us into the movie’s mystery. Haley Joel Osment gives a performance you would expect from an old pro, complex and perfectly times, and Bruce Willis gives one of his best performances, understated and poignant in its restraint.

The Sixth Sense is one of those wonderfully entertaining spooky movies that understands atmosphere creates suspense and worry. Shock is a different kind of movie and that isn’t what this movie cares about. It cares about suspense and surprise.

And it delivers.

On Amazon:

- The Sixth Sense — Amazon.com (U.S.)

- The Sixth Sense — Amazon.ca (Canada)