I discovered I had a broken link and my review of 2004’s Hidalgo wasn’t available so yesterday I fixed it and in the process reread it and rediscovered Roger Ebert’s review of it, which I think nails it (far better than I did). In fact, his conclusion is a very succinct capsule of all you really need to know:

Whether you like movies like this, only you can say. But if you do not have some secret place in your soul that still responds even a little to brave cowboys, beautiful princesses and noble horses, then you are way too grown up and need to cut back on cable news. And please ignore any tiresome scolds who complain that the movie is not really based on fact. Duh.

I really like this movie and despite my take on it not being the best, I’m putting it up again. Written in 2004:

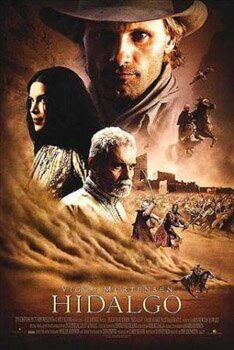

Hidalgo (2004)

Directed by Joe Johnston

Directed by Joe Johnston

I don’t quite understand why Hidalgo came and went with little notice, but it did and that’s too bad. I quite liked it. We’ve seen many action-adventure type movies recently that aspire to capturing something of the Indiana Jones movies but it seems to me Hidalgo is one of the few that even comes close to doing that.

Despite modern elements, including computer work, it has some intuitive understanding of the source of the Indian Jones films, old Hollywood B movies. (It does, however, take huge liberties.)

I recall one review I came across that thought the movie would have worked better if the main character, Frank Hopkins played by Viggo Mortensen, had been more of a wisecracking hero. It struck me that the movie must have sailed right over that reviewer’s head.

Had the movie gone that way with the character portrayal we would have had yet another movie with of the endless, cookie-cutter heroes who populate the incessant stream of adventure drek we keep getting. And heaven knows, we have enough of those to last several lifetimes.

The review also appears to have missed the strong note of humour running through Hidalgo, perhaps because it’s dry and, sometimes, rather subtle. A wise-cracking Hopkins would have been like playin Hannibal Lector like Inspector Clouseau.

Hidalgo is another of those Hollywood movies that mixes styles – generally, not a good idea given the results we often get.

In some ways, this is a weakness of the film but, that being said, quite often it does work.

The movie tries to be a western and action-adventure film at the same time. This is difficult to pull off because westerns work best with simplicity whereas action-adventure films, while simple in story, are spectacles. Visually, the two genres are at opposite ends of the scale.

However, Hidalgo gets away with it by and large. I think this is due to a great, understated performance by Viggo Mortensen. To be honest, he and a few of the other actors are a bit better than the movie really deserves. But thanks to them, a movie that’s a little run-of-the-mill becomes something much better.

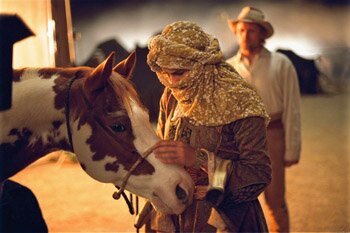

The story is straightforward: a cowboy, part Indian, part white, is something of a drunkard having hidden the native part of his lineage in order to fit in better.

However, he’s also the cowboy who takes orders to U.S. troops at Wounded Knee Creek, the orders that eventually led to the massacre of natives there.

Burdened by guilt and being someone who lacks an identity – neither Indian nor white, a lost man – he works clownishly in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, living off his reputation as the best long-distance rider.

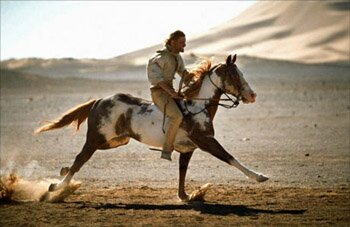

To cut to the quick: he’s invited to go across the ocean and ride in the great Arab race, The Ocean of Fire, a 3000 mile life-threatening competition. He accepts, and the movie is about the race. And Hopkins is, of course, accompanied by his horse, Hidalgo.

While there are certain absurdities to the movie, factual and realistic fallacies, I like Roger Ebert’s take on it.

If you’re familiar with a certain kind of Hollywood movie, if you’ve loved them, these aren’t problems.

They aren’t what the movie is about. It’s about a hero facing obstacles and overcoming them. At the risk of overstatement, it’s mythical in that way. It’s why we like it and why we don’t give a rat’s behind about how likely or “true” it may be.

It’s fun, invigorating and satisfying – the good guy wins.

While largely a fun ride, Hidalgo is about a man discovering himself. It’s a film about redemption. In native terms, the horse Hidalgo acts as a kind of spirit guide for Hopkins, often simply by its presence and tenacity.

I really enjoyed this movie. If I had my way, I would of toned down the action-adventure aspects and played up the western since it captures all the best elements of the genre – the simplicity and the moral tale of a man finding himself, his honour and nobility.

But that’s kind of quibbling. The movie is fun and Mortensen demonstrates that not only can he carry a movie, he is made to carry them.

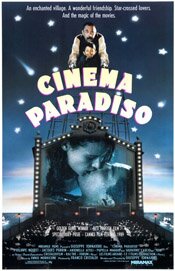

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Cinema Paradiso (1988) But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life. Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting. Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

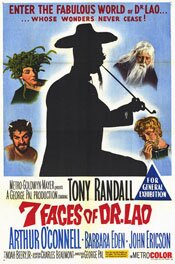

To begin with, though dressed up in western garb the movie takes its first left turn when its lead character, Dr. Lao played by Tony Randall, shows up. He is Chinese – or is he? His accent changes as the situation demands, deliberately. Dr. Lao has brought his circus to the town of Abilone (and Randall plays all the characters in the circus, including Merlin and the Abominable Snowman).

To begin with, though dressed up in western garb the movie takes its first left turn when its lead character, Dr. Lao played by Tony Randall, shows up. He is Chinese – or is he? His accent changes as the situation demands, deliberately. Dr. Lao has brought his circus to the town of Abilone (and Randall plays all the characters in the circus, including Merlin and the Abominable Snowman). Several things make the movie stand out. The first is the unusual use of an Asian as the lead character – something unheard of for the period (1964) and especially so for a western. However, typical of the period, the Asian isn’t Asian – it’s a white Hollywood actor (Tony Randall) doing a characterization of an Asian (which, like Mickey Rooney’s Japanese man in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, probably makes the hair stand on end for anyone from an Asian country).

Several things make the movie stand out. The first is the unusual use of an Asian as the lead character – something unheard of for the period (1964) and especially so for a western. However, typical of the period, the Asian isn’t Asian – it’s a white Hollywood actor (Tony Randall) doing a characterization of an Asian (which, like Mickey Rooney’s Japanese man in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, probably makes the hair stand on end for anyone from an Asian country).

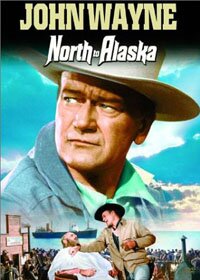

Directed by Henry Hathaway

Directed by Henry Hathaway