It’s hard to think of John Wayne and romance at the same time. The image of one and the image of the other don’t rest well side by side; one seems to negate the other.

Is Hondo the definitive John Wayne movie?

I don’t thing many people would argue that Hondo is the best of John Wayne’s movies. Similarly, I don’t many will argue against it being among his best both as a western and as a performance from Wayne. But if ever there was a movie that illustrated what John Wayne did onscreen, how he came across and essentially provided a definition for those words “John Wayne,” it’s Hondo.

Mister Roberts more drama than comedy

Mister Roberts is a much-loved movie so I always feel bad when I say that for me it’s just so-so. I kinda like it; I kinda don’t like. It may be due to not being much of a fan of either Henry Fonda or Jack Lemmon. (My mother loved Jack Lemmon.) I admire Fonda more than like him.

The great and debatable Red River

I really go on a ramble here about this movie, though it is more a ramble about John Wayne’s acting and speech pattern than the film. This is considered one of the great westerns by many and I would be among them. However, while I like Wayne in it and think it’s one of his best roles, it is not my favourite John Wayne performance.

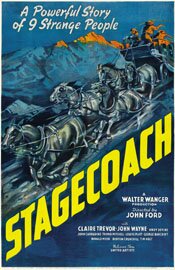

An imposing little Stagecoach from John Ford

When you think of how long it takes to make a movie today, at least a Hollywood movie, it’s quite astonishing to find John Ford cranked out three pretty extraordinary movies in 1939. His “go to” guys in that period were Henry Fonda and John Wayne. (In 1939-1940, he made five films — three with Fonda, two with Wayne.)

The number of movies isn’t the amazing part, though it is notable; what is remarkable is the quality of those films. (The movies are Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home.) For many, that creative glut would be a career. With Ford, some of his best films were still ahead of him.

Stagecoach (1939)

Stagecoach (1939)

Directed by John Ford

For what is essentially a simple western, Stagecoach is a pretty imposing little film. It’s daunting for all the film history associated with it, beginning with the introduction of John Wayne as movie star. (His first starring role was in Raoul Walsh’s 1930 movie The Big Trail. But it was John Ford and Stagecoach that made him a star.)

Interestingly, Wayne wasn’t the big star of Stagecoach. Claire Trevor was. She gets top billing and the movie is an ensemble piece, so no one character really dominates as they do in a “star vehicle.”

The movie also gave us Monument Valley, in Utah, which would afterward be forever associated with John Ford and be the quintessential “old West” landscape with its plateaus, mesas and buttes. And for many, this is the movie where Ford’s cinematic eye for people and landscapes — often low-angled shots; often sky dominated — is first seen.

There is one shot in particular that I loved. The upper two thirds of the frame is cloud fluffed sky. The lower third is plateau with a mesa off to the right; nothing but dessert otherwise, but for a trail with the lonely stagecoach winding along it from right to left, small and vulnerable.

The story is simple enough and one that is standard fare now: a group of people on their way from here to there, in this case on a stagecoach, encountering and overcoming various threats along the way.

In this movie, the threat comes from Geronimo as the stagecoach is passing through hostile Apache territory.

Riding the stage with the marshal (George Bancroft) are the “proper” lady, Lucy (Louise Platt) and the banker (Berton Churchill) … and a number of social outsiders. The hooker, the drunk, the outlaw … all with stronger moral codes than those who make up the proper society from which they’re excluded.

Both Dallas (the hooker) and the constantly inebriated Doc Boone (Thomas Mitchell) have been run out of town by self-appointed guardians of social mores.

Along the way, they meet up with the Ringo Kid (John Wayne), the outlaw. Though a disparate group and one at odds with itself, it is in working together that they make it to their destination.

As far as the story goes, the movie is nothing exceptional, at least not today. It’s significance is in what it means historically, as far as cinema goes, and John Ford’s directorial work.

Even though many of the things Ford did have since been copied and have become fairly common, the look of Stagecoach is still striking; more so when seen in its historical context.

For any serious lover of westerns, this movie is a must.

Apart from being at the start of an extraordinary string of westerns from John Ford that cover decades, it also gives us that moment when the camera moves in on John Wayne’s face announcing, in no uncertain terms, “Meet your favourite star for the next forty years.”

Yes, John Wayne was around for a long time after this movie came out. It should also be mentioned that simply as a movie, this is one very good film.

(In this same year, 1939, Ford would also direct Young Mr. Lincoln and Drums Along the Mohawk.)

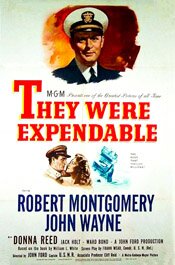

John Ford, John Wayne and Expendable

Sometimes the release dates of movies can be significant. Get it wrong and you’re all in a muddle, as I was when I watched They Were Expendable.

The movie itself isn’t anything I would say you should rush out to see unless you’re a really big John Ford and/or John Wayne fan. The tone of it is curious, however, given the kind of movie it is and what it is about. Some movies are intriguing despite not being great films and that is the case with this one.

They Were Expendable (1945)

They Were Expendable (1945)

Directed by John Ford

I was very confused when I watched the war movie They Were Expendable because I thought it was from 1941. It turns out that is when the movie is set as it opens. My confusion evaporated, however, when I realized it was from 1945, though it is still an unusual movie that John Ford gives us.

Believe me, with this movie the year really matters – especially if you confuse it with four years earlier.

This movie was released in December of 1945. In World War II, Japan formally surrendered in September of 1945.

The movie is somber recounting of the early days of the war for the U.S., beginning with the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941.

Made with the approval and assistance of the U.S. Navy, Army and Coast Guard, it shows us the U.S. getting its behind kicked by the Japanese – starting in Pearl Harbor and continuing through the Philippines.

Audiences at the time of the film’s release, however, would be fully and completely aware of the end result of it all – victory in the Pacific; Japan’s surrender.

The reason John Ford shows us all the bad news from the war’s early days is because he’s telling the story of the PT boats – how their role in the war came about (they weren’t highly regarded originally), how they won respect and the sacrifices made by the crews that worked them. (The tagline was, “A tribute to those who did so much… with so little!”) However, the main character is really the boat itself.

The movie is a solemn tribute and sober homage but also full of patriotism which, appropriate to the period of its release, may strike a current day viewer as a bit much.

There are good action scenes in the movie as well as some interesting, almost noir-ish lighting in others. The movie itself appears to be in poor shape, at least on the DVD copy I have. I don’t know if any restorative work went into it but it doesn’t appear so given the scratches in a number of scenes. I’m a bit surprised it comes to use from Warner Brothers. It may have something to do with the lack of good original film materials. I don’t know.

Overall, I can’t say this is a great movie. It’s a curious one, however. It’s worth seeing at least once, especially if you’re a fan of either John Ford or John Wayne. Just keep in mind this movie should probably be viewed as a propaganda work.

And maybe that is what makes it peculiar. It’s quite a bit of “Rah, rah!” about PT boats but seems to also want to be a solid drama and thus it acquires a bipolar quality.

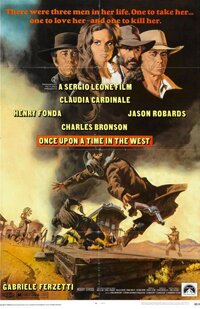

20 Movies: Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Look out. I’m back to westerns. I love them.

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

directed by Sergio Leone

From it’s incredible opening to the closing credits, Once Upon a Time in the West is a mesmerizing movie about westerns. In a way, it isn’t even about westerns. It simply evokes them with a stream of iconic images.

The movie takes a simple, almost cookie cutter story, and uses it as a basis (and excuse) for a film that is essentially concerned with western myths and iconography. (Sergio Leone had done this before, as in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.)

It’s a post-modern film; it takes a kind of deconstructionist approach to movie-making (which may seem a tiresome idea today but was unusual in 1969).

At the centre of the film’s narrative is Claudia Cardinale as Jill. Around her three other characters revolve: Henry Fonda as Frank, Jason Robards as Cheyenne and Charles Bronson as the man with no name (often referred to as Harmonica).

The owner of a railroad company, Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), hires a psychotic gunfighter, Frank (Henry Fonda) to get rid of anyone in the way of the completion of his railroad.

The owner of a railroad company, Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), hires a psychotic gunfighter, Frank (Henry Fonda) to get rid of anyone in the way of the completion of his railroad.

Frank does, by massacring the family of new bride, ex-whore, Jill.

With her new family dead, Jill must decide what to do with the land she has inherited. It seems worthless but proves to be very valuable, so valuable it is the reason her family has been killed. It’s a basic western formula: bad guys after the good guy’s land. He must defend it and himself, except in this case “he” is “she.”

At the same time, bad-guy Frank starts being stalked by a mysterious stranger (Charles Bronson). Frank doesn’t recognize him, he has no idea what the stranger wants. As for Jason Robards’ Cheyenne, he gets involved in all of this because Frank has framed him for the killing of Jill’s family.

At the same time, bad-guy Frank starts being stalked by a mysterious stranger (Charles Bronson). Frank doesn’t recognize him, he has no idea what the stranger wants. As for Jason Robards’ Cheyenne, he gets involved in all of this because Frank has framed him for the killing of Jill’s family.

For a film almost three hours long, it doesn’t seem much to work with. But Leone is interested in the storyline only to the extent that it provides him something to improvise on western themes and imagery. He plays with these and it is what he does with them that makes this such a great movie.

I can’t imagine how this would look in pan-and-scan form. Leone makes incredible use of the screen’s width, visually stretching it out with foregrounds oriented to one side and breathtaking backgrounds to the other.

He also contrasts the breadth and spaciousness of his wide shots with the most extreme of close-ups. He shoots human faces almost as if they, too, were landscapes. The opening sequence is a spectacular example of this as he lingers on the bored killers’ faces. He shows us every detail from lines to whiskers. You almost get the sense he uses only two shots – very close or very long.

He also contrasts the breadth and spaciousness of his wide shots with the most extreme of close-ups. He shoots human faces almost as if they, too, were landscapes. The opening sequence is a spectacular example of this as he lingers on the bored killers’ faces. He shows us every detail from lines to whiskers. You almost get the sense he uses only two shots – very close or very long.

He also uses his trademark technique of drawing scenes out to their absolute limit. The opening goes something like eight minutes before anyone says anything and it is a scene simply about three guys waiting at a train station. You get an almost visceral sense of their tedium.

With scenes like gunfights, they are choregraphed to evoke iconic imagery and are paced, again, incredibly slowly to draw them out to their limits. When violence does erupt, it is explosive and very brief. Leone has little interest in violence itself but is obsessed with its rituals.

Whether the movie is about anything is debateable. Leone seems interested primarily in style and evoking the western. (Once Upon a Time in the West is littered with references to earlier Hollywood westerns like High Noon, The Searchers and numerous John Ford films. It’s even partly shot in Monument Valley where Ford shot so many of his westerns.)

Whether the movie is about anything is debateable. Leone seems interested primarily in style and evoking the western. (Once Upon a Time in the West is littered with references to earlier Hollywood westerns like High Noon, The Searchers and numerous John Ford films. It’s even partly shot in Monument Valley where Ford shot so many of his westerns.)

If there is a comment in the film, perhaps it is a critique of myths of America. In the film, everyone is dissatisfied. Everyone wants something more, from the railroad baron and his hired killer Frank, to the woman Jill and Jason Robards. In the land of the free, no one seems to be content with their lot (except, perhaps, for the murdered McBain.)

There may be something to the use of the railroad, too. Its arrival signals the end of the mythological West and the beginning of the modern age in the last American frontier. The train represents encroaching European civilization and the end of the mythical West, just as the film Once Upon a Time in America is a eulogistic end of the western.

There may be something to the use of the railroad, too. Its arrival signals the end of the mythological West and the beginning of the modern age in the last American frontier. The train represents encroaching European civilization and the end of the mythical West, just as the film Once Upon a Time in America is a eulogistic end of the western.

But in the end, the film is simply a great homage to westerns, as well as a kind of eulogy to them. It’s a stream of riveting images; an almost symphonic evocation of filmmaking style.

Donovan’s Reef: Fisticuffs anyone?

I took a shot at assessing another John Wayne movie (since I’d been doing quite a few of those lately). Here’s what I came up with:

Donovan’s Reef (1963)

This is a difficult film to defend, much less recommend, for many reasons, most of which have to do with director John Ford. Still, if I may refer to Glenn Erickson who, in his review, refers to Andrew Sarris in The American Cinema, “…Donovan’s Reef was like some kind of heaven that Tom Doniphon and Liberty Valance, both fun-loving uncivilized types, had retreated to in the afterlife. And it’s the key to appreciating this broad comedy.”

This is a difficult film to defend, much less recommend, for many reasons, most of which have to do with director John Ford. Still, if I may refer to Glenn Erickson who, in his review, refers to Andrew Sarris in The American Cinema, “…Donovan’s Reef was like some kind of heaven that Tom Doniphon and Liberty Valance, both fun-loving uncivilized types, had retreated to in the afterlife. And it’s the key to appreciating this broad comedy.”

In other words, Donovan’s Reef is fantasy. It also recapitulates many of the themes and sentiments that characterize the John Ford canon. You could call it a kind of executive summary. Unfortunately, many of those themes and sentiments are more than a little disagreeable, even offensive, to a modern sensibility, like the racial and gender characterizations.

Compounding that is the structure and style of the film which is somewhat clunky. I think Erickson describes it pretty well when he writes that it is, “…a surreal, almost abstract progression of kabuki-like rituals from the world of John Ford.”

The movie comes across as a collection of set pieces that are only loosely tied together. It’s almost episodic. These set pieces, however, are like a highlighting of key aspects of Ford’s work – again, almost like an executive summary. Many of these conclude with brawls – many of them seem to be excuses for brawl scenes – fights that involve almost everyone and where no one gets hurt.

The movie comes across as a collection of set pieces that are only loosely tied together. It’s almost episodic. These set pieces, however, are like a highlighting of key aspects of Ford’s work – again, almost like an executive summary. Many of these conclude with brawls – many of them seem to be excuses for brawl scenes – fights that involve almost everyone and where no one gets hurt.

It’s all set in an idyllic, mythical South Seas world called Haleakaloa. It stars John Wayne and Lee Marvin as two brawling pals who like drinking and fighting, and being their own men. There is a romance that reiterates Ford’s vision of relationships between men – antagonistic, but in a charming way.

But is it a good movie? I would have to say no even though I did enjoy it. Despite the similarity to North to Alaska, the film it most reminds me of is Hatari! That movie, directed by Howard Hawks, is long and meandering. It seems to be more about spending time with the characters. This how Donovan’s Reef strikes me. The story is flimsy at best. The movie is more about spending time with Wayne, Marvin and, in behind the scenes, Ford in a fantasy paradise. It’s almost like sitting around with old friends and having a few beers.

This is why I can enjoy the movie. If you’re familiar with Ford/Wayne movies, if you grew up with them and liked them, you can enjoy the movie, though you couldn’t credibly argue for it being a “good” movie. At least, I don’t think so.

And if you didn’t grow up with these guys, if you’re unfamiliar with the sensibility and are unwilling to turn a blind eye to some of the stereotyping and so on (rather like sitting down with a politically incorrect grandfather who, smiling, unthinkingly throws out inappropriate remarks) … No, you won’t like this movie.

And if you didn’t grow up with these guys, if you’re unfamiliar with the sensibility and are unwilling to turn a blind eye to some of the stereotyping and so on (rather like sitting down with a politically incorrect grandfather who, smiling, unthinkingly throws out inappropriate remarks) … No, you won’t like this movie.

But then, the movie was never made for you. It’s more like a greeting card sent to old friends from Ford, full of the John Ford “stuff,” from the characters to the scenes.

1½ stars out of 4.

3 Godfathers: A western as Christmas fable

Having come across 3 Godfathers in a number of “top Christmas movies” lists, I decided to watch it. A second time. I had watched it about two years ago but I couldn’t recall it, and definitely didn’t recall the Christmas aspect. Now, having seen it again, I see the Christmas angle but I don’t personally consider it a Christmas movie. It plays like a western – an odd one, granted – and with no Christmas “feel,” at least not for me. Here’s the review I wrote:

Review – 3 Godfathers

The 1948 John Ford movie 3 Godfathers is, if nothing else, damn odd. And, to be honest, I’d have to say it’s ill-considered. It’s a western as Christmas-tale where three outlaws become something akin to the three wise men of the New Testament, but not really, and in the process reveal themselves as three bad guys who are really, really nice once you get to know them.

The 1948 John Ford movie 3 Godfathers is, if nothing else, damn odd. And, to be honest, I’d have to say it’s ill-considered. It’s a western as Christmas-tale where three outlaws become something akin to the three wise men of the New Testament, but not really, and in the process reveal themselves as three bad guys who are really, really nice once you get to know them.

The film is dedicated to Harry Carey. John Wayne is the star. It co-stars Carey’s son, Harry Carey Jr. (in what I believe to be his first film). It also co-stars Pedro Armendáriz. The three, Wayne, Carey Jr. and Armendáriz, are three outlaws who arrive at the town of Welcome, Arizona, roughly around Christmas time, with the intention of robbing the bank.

When they first arrive they meet a friendly fellow with whom they begin to josh and converse. As the encounter ends, they discover he’s the town’s sheriff (Ward Bond), a man who has a pretty good idea of what kind of men they are and what they’re intentions might be.

So they rob the bank and in short order the sheriff has a posse out after them. Soon, the sheriff realizes that Wayne’s character, Robert Hightower, is a clever man and the chase becomes something of a game for him, the sheriff. It’s a challenge – he looks forward to catching Wayne and playing chess once he’s in prison.

The chase takes the outlaws out into the desert where they are in search of water and shelter. It’s not easy – one of them is wounded. Each time they come upon water, the sheriff and the posse are there ahead of them so they have to go searching for water elsewhere.

The chase takes the outlaws out into the desert where they are in search of water and shelter. It’s not easy – one of them is wounded. Each time they come upon water, the sheriff and the posse are there ahead of them so they have to go searching for water elsewhere.

So far, so good. It’s an average western – not great, but not bad. But then they come upon a dying woman who is about to give birth. They help her with the birth. The child is born but his mother is dying. Before she does, however, she names the child after the three outlaws, appoints those same outlaws as the child’s godfathers, and makes them promise to care for the child.

The story movie now takes a weird turn where the western continues but a variety of religious elements – symbols and speeches and so on – begin to populate it. (These actually begin back with the woman giving birth to her baby – it is Christmas time.)

The three men care for the child passionately. Two of them perish in the end, for the sake of the child, and the third, Wayne, all but dies. He manages to survive, saving the child, but is caught by the sheriff. He’s taken back to the town of Welcome where he will face trial and a potential sentence of 20 years if found guilty.

The odd thing here (as if things haven’t been peculiar enough) is everyone is friendly, best buds, even though Wayne is in jail and going to court.

As might be expected with a Christmas film (that never really feels like a Christmas film), there is a happy ending to it all.

And it’s all just so damn odd.

On the plus side, however, I think this movie has one of the most interesting performances from John Wayne. He seems more emotive than we usually see him, and there is more animation in his face than usual. He has a nice speech in a scene where he tells the other outlaws about finding a pregnant woman in an abandoned wagon. It’s hard to say whether it’s one of his better performances, though, since the film is so strange. Is he good? Is it over the top? I really don’t know.

I can say this, though: Ward Bond is very good. And so is Harry Carey Jr., especially for a first film. (It’s not his fault the part is written the way it is.)

Also excellent in the film: the cinematography. The shots in the desert are really quite magnificent. The visual look of the movie is very John Ford, very good.

Overall, however, I’d have to say this is a wrong-headed film. It’s the wrong kind of story for John Ford. Apart from being a Christmas western (which just sounds weird), this essentially sentimental, feel-good story is Frank Capra country, not John Ford. Ford doesn’t seem to finesse this kind of story where we can accept the sentimentality – probably because of the western austerity and harshness that plays through most of the film.

Mind you, in its historical context, the Christmas aspect might have played better to an audience of the day than a contemporary one. But for me this is a curious movie but not a particularly good one.

2 stars out of 4.