I stumbled upon Strange Cargo last night and rarely has the word “strange” in a title been used so appropriately. This movie is strange indeed. It’s also a pretty good adventure film starring Joan Crawford and Clark Gable (the latter’s previous movie was Gone With the Wind).

Strange Cargo (1940)

Strange Cargo (1940)

Directed by Frank Borzage

Crawford and Gable are two feisty lovers with a stormy relationship. Neither is a person of outstanding character. The storminess was likely easy for both to convey because in reality the pair, who had a prior relationship, detested one another.

In the movie, Crawford is essentially a hooker (though Hollywood censorship of the period means this is only vaguely suggested). Gable is a nasty, self-centered rogue who manages to be charming at the same time.

We find them on Devil’s Island (French Guiana) where they get mixed up with a group of convicts in an escape attempt. The majority of the movie is the struggles and conflicts of this rag tag bunch as they make their way through the jungle and swamps of the island and then on board a small ship as they try to get away.

Fine enough, and a pretty de rigueur setting for an adventure of the period. But there is an element in the movie that makes it anything but de rigueur. That element is the character of Cambreau, played by Ian Hunter. He appears mysteriously and joins the convicts in their escape but he is not your usual prisoner.

Cambreau is a Christ-like figure that steers the movie into religious allegory and allows the film to meditate on subjects like God, morality, ethics and honour. While this may not sound appealing (and yes, occasionally it is a little heavy-handed), the mysterious quality Hunter’s Cambreau figure brings adds to the adventure.

Gable, by the way, objected to this aspect of the movie. He thought it would prompt audiences to stay away. In his opinion, people expected love and sex in a Crawford-Gable movie.

Both Crawford and Gable are wonderful in the movie, particularly Crawford as the slatternly Julie. I read somewhere that Crawford was quite proud of the way she put her “star” image aside and portrayed the character. I noticed how in many scenes she adds small, subtle touches to communicate the character’s “low rent” status, such as one scene where it is in how she sits (not what my mother would have called “lady-like”.)

She also went without makeup or false eyelashes and her costume, essentially two dresses, was from a bargain boutique.

Gable is equally unglamorous in his appearance, wearing torn clothes and growing increasingly unshaven as the movie progresses. In fact, the movie appears to make a concerted effort to ensure both its stars are unstar-like, visually.

The end result is a movie that is peculiar yet compelling, partly due to its oddness. The Cambreau character, while bringing in the religious element, also adds mystery to the overall adventure as no one ever quite knows who he is.

On the other hand, some scenes aren’t subtle in communicating the Christ figure aspect, such as the scene near the end when Cambreau is in the stormy waters with his arms out, as if on a cross.

Yes, Strange Cargo is an odd movie. But it’s worth seeing at least once, especially if you’re a Gable or Crawford fan.

An aside … According to Warren Harris in Clark Gable: A Biography, this movie was made at a time when “Joan Crawford, whose box-office popularity had sunk an all-time low, had talked L.B. Mayer into teaming them (Gable and Crawford) for the first time since the 1936 Love On the Run, which was also Crawford’s last hit.”

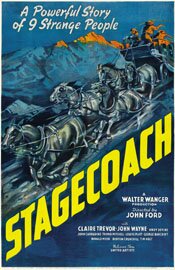

Stagecoach (1939)

Stagecoach (1939)