Call it a tall tale, a shaggy dog story or any of the other variations, this is a movie that uses exaggeration and fable to tell a story that centres around another romantic tall tale. And it works much better now, ten or more years later, with distance from the marketing and celebrity media atmosphere that surrounded it when released.

Errol Flynn loses a step, gains some gravity

No snide comment is implied by “Errol Flynn … gains some gravity,” though by the time this movie was made the older Flynn had put on a few pounds. Rather, his performance has a bit of weight that wasn’t there in the younger Flynn’s roles. You can see it in this movie, The Master of Ballantrae, though I don’t think anyone would rate the movie itself terribly high.

Crawford and Gable and the oddball Strange Cargo

I stumbled upon Strange Cargo last night and rarely has the word “strange” in a title been used so appropriately. This movie is strange indeed. It’s also a pretty good adventure film starring Joan Crawford and Clark Gable (the latter’s previous movie was Gone With the Wind).

Strange Cargo (1940)

Strange Cargo (1940)

Directed by Frank Borzage

Crawford and Gable are two feisty lovers with a stormy relationship. Neither is a person of outstanding character. The storminess was likely easy for both to convey because in reality the pair, who had a prior relationship, detested one another.

In the movie, Crawford is essentially a hooker (though Hollywood censorship of the period means this is only vaguely suggested). Gable is a nasty, self-centered rogue who manages to be charming at the same time.

We find them on Devil’s Island (French Guiana) where they get mixed up with a group of convicts in an escape attempt. The majority of the movie is the struggles and conflicts of this rag tag bunch as they make their way through the jungle and swamps of the island and then on board a small ship as they try to get away.

Fine enough, and a pretty de rigueur setting for an adventure of the period. But there is an element in the movie that makes it anything but de rigueur. That element is the character of Cambreau, played by Ian Hunter. He appears mysteriously and joins the convicts in their escape but he is not your usual prisoner.

Cambreau is a Christ-like figure that steers the movie into religious allegory and allows the film to meditate on subjects like God, morality, ethics and honour. While this may not sound appealing (and yes, occasionally it is a little heavy-handed), the mysterious quality Hunter’s Cambreau figure brings adds to the adventure.

Gable, by the way, objected to this aspect of the movie. He thought it would prompt audiences to stay away. In his opinion, people expected love and sex in a Crawford-Gable movie.

Both Crawford and Gable are wonderful in the movie, particularly Crawford as the slatternly Julie. I read somewhere that Crawford was quite proud of the way she put her “star” image aside and portrayed the character. I noticed how in many scenes she adds small, subtle touches to communicate the character’s “low rent” status, such as one scene where it is in how she sits (not what my mother would have called “lady-like”.)

She also went without makeup or false eyelashes and her costume, essentially two dresses, was from a bargain boutique.

Gable is equally unglamorous in his appearance, wearing torn clothes and growing increasingly unshaven as the movie progresses. In fact, the movie appears to make a concerted effort to ensure both its stars are unstar-like, visually.

The end result is a movie that is peculiar yet compelling, partly due to its oddness. The Cambreau character, while bringing in the religious element, also adds mystery to the overall adventure as no one ever quite knows who he is.

On the other hand, some scenes aren’t subtle in communicating the Christ figure aspect, such as the scene near the end when Cambreau is in the stormy waters with his arms out, as if on a cross.

Yes, Strange Cargo is an odd movie. But it’s worth seeing at least once, especially if you’re a Gable or Crawford fan.

An aside … According to Warren Harris in Clark Gable: A Biography, this movie was made at a time when “Joan Crawford, whose box-office popularity had sunk an all-time low, had talked L.B. Mayer into teaming them (Gable and Crawford) for the first time since the 1936 Love On the Run, which was also Crawford’s last hit.”

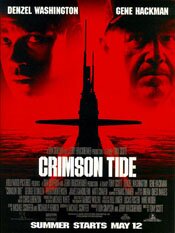

Characters in close quarters – Crimson Tide

You wouldn’t immediately associate submarine movies with a film like Key Largo but they have something in common. The dramatic tension comes about by having characters constrained within close quarters. In Key Largo, it’s within a hotel because of a hurricane; in submarine movies it’s due to the nature of submarines.

I don’t like a phrase like “submarine movies” but there is no getting around the fact there is a kind of sub-category of action-adventure films characterized by where they are set — on submarines. They’re often among the best of the action-adventure variety of films because of the close quarters that seem to force filmmakers to concentrate on characters.

Crimson Tide (1995)

Crimson Tide (1995)

Directed by Tony Scott

In the tradition of movies like Run Silent, Run Deep, The Hunt for Red October and Das Boot, the Tony Scott directed Crimson Tide is submarine drama with strong lead characters. If it distinguishes itself from those previous movies it is by being faster moving and much noisier.

That may not sound overly appealing but it be would wrong to think that way. This is a very good, very engaging action-adventure with a strong foundation: the performances of Denzel Washington and Gene Hackman.

It’s also supported by strong performances by its supporting cast – Matt Craven, George Dzundza, Viggo Mortensen and James Gandolfini, to name a few.

Without its strong cast, I think this would likely be just an average film but with them it is firmly anchored.

There is a state civil war in Russia. Rebel generals have taken over a base with nuclear weapons and it appears as if they may use them. The U.S. naval sub Alabama, nuclear-armed, is sent to Asian waters to await instructions. They get them: prepare your missiles. A further message, only partially received, may be orders to fire them or to stand down. It is unclear.

The movie’s conflict is between the sub’s captain (Gene Hackman) and its new executive officer (Denzel Washington). For the missiles to be fired, the two must be in agreement. They aren’t. The captain wants to fire; his second in command does not.

What makes movies like this dramatic and appealing (and you see this in films like Run Silent and Red October) is that the “bad guy” is external – off set. The leads, in this case Hackman and Washington, are both good guys but they are at opposing ends about what to do and thus in conflict.

This increases the film’s conflict by removing the easy, black and white choice and while an audiences’ sympathy may align with one, they can’t easily dismiss the other.

This is also reflected in the unfolding of the film’s drama where the sub’s crew must choose sides, many of whom are conflicted (like Mortensen’s Lt. Ince). We end up with struggles in the submarine, including mutiny, because of the lack of clarity. It’s all due to the ambiguity of the last orders received.

The movie doesn’t ease its audience into the story; it throws them in head first. Music and editing thrum as it begins with a journalist describing events in Russia. There is no slow unfolding of exposition. Director Scott and producer Jerry Bruckheimer take the approach of throwing the audience in at full speed. Details fly by like rapid fire flash cards.

In some movies, this is noise and fury approach can be a gimmick to mask an uninspired story but in Crimson Tide it’s a quick and effective way to get quickly to what is an intelligent, well told story. Perhaps its due to the close quarters of submarines, but movies like this seem to lend themselves to dramatic, character-driven films.

While my own preference is for the quieter tension of a movie like The Hunt for Red October (which I find more effective), it works for Crimson Tide as it delivers a compelling film that leaves an audience with something to question and discuss when is over.

On the whole, this is a very good movie and well worth seeing and more than once.

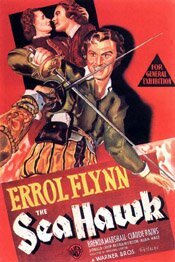

The impish Errol Flynn in a swashbuckler

A few years ago I bought a fistful of Errol Flynn movies that were in one of those many Warner Brothers collections. I had only vague memories of Flynn movies but was curious having seen The Adventures of Robin Hood and, a few years earlier, having read his autobiography, My Wicked, Wicked Ways (recommended, by the way — it is so much fun to read).

Among the movies in the collection was the one I scribbled about below, The Sea Hawk. Interestingly, just as Robin Hood was directed (in part) by Michael Curtiz, he also directs this movie. He seems to have been aware of what Flynn brought to these movies and was very good at getting it.

The Sea Hawk (1940)

The Sea Hawk (1940)

Directed by Michael Curtiz

I’m halfway through Errol Flynn: The Signature Collection and I think I’ve hit the real gem of the lot. (Not that the others aren’t good too.) It’s The Sea Hawk and it really does put the “swash” in swashbuckler.

It’s absolutely brilliant and in a number of respects. I can’t help comparing it to The Adventures of Robin Hood. It has much of the same feel while at the same time has a little something different.

For one thing, both films capture a sense of fun and exuberance. Both also manage to be rousing costume adventures without any sense of self-consciousness though The Sea Hawk differs slightly in that Errol Flynn plays the British pirate Captain Geoffrey Thorpe with a kind of very contained impishness.

His captain is apparently quite serious, patriotic and heroic, yet every now and then he seems to be restraining a smile or grin.

As someone in the special feature on the DVD says (The Sea Hawk: Flynn in Action), it’s almost as if Flynn is asking the audience, “Are you really buying this?”

But in these Flynn movies this kind of feeling is not one of mocking the audience but of having fun with them. Flynn seems to play his swashbuckling roles the way the early Springsteen played concerts – the more fun the audience had, the more fun he had and together they create a kind of synergistic relationship.

Another fascinating way in which The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Sea Hawk compare is in their look. Where Robin Hood is an incredibly exuberant display of colour, The Sea Hawk is nothing less than a magnificent example of black and white. (Although I could have done without the Panama scenes done in sepia.)

The sea battles between the ships are fabulous.

We know from recent films like Master and Commander that great sea battles can be done in colour but I’ll take The Sea Hawk’s scenes anytime. (It’s also incredible to think these were done on sets.)

There is also a great sword fight (as there must be to conclude an Errol Flynn swashbuckler) where, again, the black and white scenes with their use of light and shadow are exceptional. I loved the great shadows on the walls during the struggle.

The Sea Hawk is about as close to the quintessential swashbuckler as you can get. It has Errol Flynn, the man who pretty much defines the hero of such movies.

It has the great set pieces like the sea battles and the swordfights. And it has the music that has influenced the sound of almost all heroic adventures.

Credit for the music goes to Erich Wolfgang Korngold. His score (which is apparently not just rousing but quite clever as it uses, in part, themes from the earlier The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex but in a reworked form), is operatic which, if you think about it, is really what such romantic adventures require.

I really didn’t know a great deal about The Sea Hawk before watching it. And to be honest, I wasn’t expecting a great deal. I basically put it in the DVD player because I wanted to watch something and I hadn’t seen this one yet.

As often happens, when I was least expecting it, I encountered a wonderful movie. Highly recommended.

(The Sea Hawk also aired last night on TCM. I missed it but I may watch my copy again tonight. The above was written roughly about April 2005.)

Chess games and submarine movies

You might think that movies set on submarines are relatively rare. They are — relatively. But as a quick search online will show you (as it just showed me), there are actually quite a few of them. (Das Boot and Crimson Tide come to mind.) Relative to other movies, they may be rare. But there are quite a few of them nonetheless.

This leads me to the two movies I wanted to bring up: Run Silent, Run Deep (1958) and The Hunt for Red October (1990). I don’t know what the correct term for describing them would be — suspense, thriller, action? I lean toward suspense but what makes them compelling is a phrase Sean Connery’s character, Marko Ramius, uses in Red October: chess game.

This leads me to the two movies I wanted to bring up: Run Silent, Run Deep (1958) and The Hunt for Red October (1990). I don’t know what the correct term for describing them would be — suspense, thriller, action? I lean toward suspense but what makes them compelling is a phrase Sean Connery’s character, Marko Ramius, uses in Red October: chess game.

There is more actual “action,” as in torpedoes and so on, in Run Silent, Run Deep, but neither film has a great deal of it. It’s the drama of the situations and, again in both films, the mystery surrounding a lead character’s motives, Clark Gable’s in Run Silent and Sean Connery’s in Red October.

Both movies get more physically and visually dramatic with action in their final acts but for the most part these chess games are mysteries rather suspense thrillers, though both are suspenseful and, I suppose, thrilling.

However they are described, I like both movies quite a lot and have watched both many times. They are well worth seeing more than once ….

Run Silent, Run Deep (1958)

I saw an interview with the actor Laurence Fishburne the other day in which he was speaking of various influences when he was young. At one point, he brought up the movie Run Silent, Run Deep and Clark Gable. What struck him in the movie was Gable’s gravitas. I immediately thought, “Yes, that is the perfect word for it.” (Read more)

The Hunt for Red October (1990)

In the class of movies known as action-adventure, The Hunt for Red October stands out as one of the best and as one of the strangest because the action is relatively minimal and doesn’t play a huge role in generating the film’s suspense and tension. (Read more)

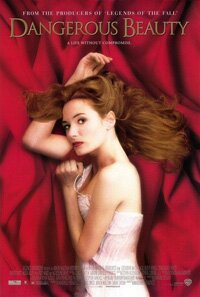

An unapologetic and satisfying romance

A friend kept telling me how much she loved this movie. I knew nothing about it but a few years ago I saw it and picked it up. I took it home, put it in the DVD player and was very happy I did.

This is a good, fun movie.

Dangerous Beauty (1998)

Dangerous Beauty (1998)

Directed by Marshall Herskovitz

What’s a girl to do? It’s 16th century Venice, wealth and politics determine the marriage bed and, with a father having squandered the family fortune away on drink, a sad match with a old man is the best a woman of few means can do.

Unless, of course, she becomes a courtesan, which is what Veronica Franco, played exquisitely by Catherine McCormack, decides to do in Dangerous Beauty.

By turns sexy, romantic and even bawdy, and generously flavoured with an almost melodramatic quality at times, Dangerous Beauty is a marvelously entertaining film that, when all is done, is ultimately an unapologetic and satisfying romance.

But unlike many costume romances, the movie does not choose to make the lead female character a damsel in distress awaiting a dark rugged hero to sweep her off her feet and carry her off to some ill-defined happily-ever-after. No, Veronica is the architect of her fate.

And Rufus Sewell as Marco Venier, the handsome if somewhat wishy-washy object of her affections, gets to go along.

And Rufus Sewell as Marco Venier, the handsome if somewhat wishy-washy object of her affections, gets to go along.

The movie works so well for several reasons. First of all, it is what it is, meaning it knows it is a romance and follows those conventions faithfully. However, it manages to go beyond them by toying with them, such as making Veronica a much stronger character than the form normally possesses.

And the Veronica character, as played by Catherine McCormack, is the ultimate key to the film’s success.

McCormack manages a nuanced performance that captures a cornucopia of emotional shadings that enunciate the character perfectly — strength, uncertainty, sauciness, love, sensuality and the steady-eyed determination of youth, among others.

I just love the mischievous grin she gets, particularly in her earlier scenes with Rufus Sewell. There is a completely disarming combination of youth and playfulness in it.

Sewell is also good, as he always is, despite a role that is quite difficult to play — the hero is not quite a hero, the man who disrupts his life due to his conflict between his love of Veronica and his sense of duty.

There is also a wonderful performance by Jacqueline Bisset as Paolo, Veronica’s somewhat stern and determined mother.

There is also a wonderful performance by Jacqueline Bisset as Paolo, Veronica’s somewhat stern and determined mother.

It is she who introduces Veronica to the life of the courtesan (and from whom, in the back story, we can probably assume Veronica gets her own strength of will).

In the end, Dangerous Beauty is a great romance and adventure. It’s sexy too. While it may have a bit of a costumed soap opera quality to it, that’s fine because it works, engaging us in its story from the very start.

The DVD

As far as I know, there is just the one version of Dangerous Beauty on DVD and, while passable, it’s a bit of a disappointment. The image is soft and I found the lack of a crisp image frustrating.

The story, however, is strong enough that you can convince yourself you can live with it. But I would certainly like to see a better presentation of the movie at some time in the future.

If they ever do, they might also want to think about including some special features. Other than some text “Production Notes” that are pretty scant, there are no special features here.

On Amazon

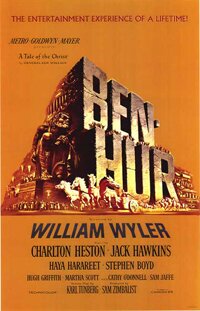

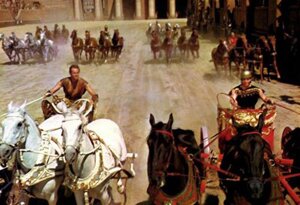

20 Movies: Ben-Hur (1959)

Let’s go big; really big. Before the world of CGI, big spectacular stuff had to be done the hard way. (No, I’m not saying CGI is easy.) It had to be done on sets, on location and with real people in the scenes.

Watch Ben-Hur and try to imagine what was involved. Now try to imagine doing that and making a movie that was actually good, one with an interesting story and captivating characters, while you’re also trying to figure out how to manage all the extras, the technical end and all the other hoo-hah that must have gone into this.

It’s really quite remarkable. Ben-Hur is an example of Hollywood doing what Hollywood tends to do, big and bloated, and actually pulling it off.

Ben-Hur (1959)

Ben-Hur (1959)

directed by William Wyler

If ever a movie deserved the term “Hollywood spectacle,” it’s 1959’s Ben-Hur from director William Wyler. More than a few dollars went into the making of this one and, to a large extent, you see those dollars on the screen.

Remarkably, it manages to be a pretty good movie too.

Ben-Hur was made in late 50s early 60s period when spectacle was the big thing in for studios. The movies arrived with an air of their own importance, a degree of pomposity that is a little hard to take today. (It may have been hard to handle back then too.)

But Ben-Hur, despite a few slip-ups, largely justifies its pretentious elements.

Like many of those “important” movies of the period, it is quite long. Part of the length is due to beginning the film with an “overture,” an image held on screen for a few minutes while loud and stirring music plays. When finished, they finally start the opening credits.

Later, after a normal film would have concluded, it pauses again a few minutes for the “entre acte,” then proceeds for another hour or so to its finish.

Today, particularly on the home editions of the film, these are historical curiosities that do little else than clog the film.

At the time, they had some purpose but for the most part were elements of the period’s pretentiousness – they served to signal the artistic importance of the movie by suggesting they were to be viewed on the artistic level of opera and symphonies.

The movie itself (subtitled A Tale of the Christ) is drawn from an earlier film (1926’s Ben-Hur) and the original 1880 novel by Lew Wallace.

The movie itself (subtitled A Tale of the Christ) is drawn from an earlier film (1926’s Ben-Hur) and the original 1880 novel by Lew Wallace.

The Christ reference is due to the presence of the life of Christ as part of the story’s background – it occurs at the time of Jesus, who appears as a character a few times in the film and has an influence on Charlton Heston as Judah Ben-Hur.

If you’ve seen Ridley Scott’s Gladiator then you have a good sense for what the story is about. Ben-Hur is a kind of well-off, aristocratic Jew at time they are living under the rule of Rome (the time of Christ). His best friend as a child was a young Roman, Messala (Stephen Boyd). The movie opens with the two boys as men, Messala returning as a Roman legionnaire to rule for Caesar over the Jews.

While still friends who love one another, the division between them of Jew and Roman quickly sets them against each other. Ben-Hur feels compelled to stand up for his people while Messala, somewhat drunk with the power Rome represents, is determined to impose his will on the Jews.

While still friends who love one another, the division between them of Jew and Roman quickly sets them against each other. Ben-Hur feels compelled to stand up for his people while Messala, somewhat drunk with the power Rome represents, is determined to impose his will on the Jews.

The acrimony between them leads Messala to use Ben-Hur as an example. Charges are brought against Ben-Hur and his family which Messala knows to be false. But he sees an opportunity to impose his will be using his friend.

Ben-Hur soon finds himself a prisoner of Rome, banished to the galleys of the Roman fleet.

He spends years as a galley slave until he saves the life of a Roman general, Quintus Arrius (Jack Hawkins), who in gratitude takes him under his wing. Ben-Hur goes to Rome where he races in the arena as a charioteer.

He spends years as a galley slave until he saves the life of a Roman general, Quintus Arrius (Jack Hawkins), who in gratitude takes him under his wing. Ben-Hur goes to Rome where he races in the arena as a charioteer.

He excels and wins honours. Arrius even adopts Ben-Hur as a son.

His freedom won, his position secured again, Ben-Hur returns home. He is focused on finding his mother and sister, and getting revenge on Messala. This leads to the great chariot race the movie is famous for, but the movie does not end there.

The final portion of the film is about Ben-Hur finding his family and struggling with his hatred of Messala and Rome within the context of the influence of Christ, particularly Christ’s final days (leading to the crucifixion).

It’s a sprawling story with numerous characters and threads. But by and large it hold together. Wyler manages an enormous task. If nothing else, Ben-Hur is a testimony and tribute to project management (as opposed to the later fiasco, Cleopatra).

It’s a sprawling story with numerous characters and threads. But by and large it hold together. Wyler manages an enormous task. If nothing else, Ben-Hur is a testimony and tribute to project management (as opposed to the later fiasco, Cleopatra).

Being large, it’s many movies at once: an historical costume drama, an action adventure, and a religious film. And each succeeds. Heston is perfect as Ben-Hur. With his granite face, he manages to communicate his character’s simmering rage at the injustice he has suffered.

In fact, the only real flaw in the film is the pretentiousness mentioned earlier. The movie probably could also us some editing to cut down its length but like a novel by Doestoyevsky, in some ways its charm is its lengthy, meandering narrative.

When people speak of movies and say such things as, “…That’s not how they use to make ’em,” Ben-Hur is an example of how Hollywood use to make them: big and large and visually riveting by virtue of its scope.

When people speak of movies and say such things as, “…That’s not how they use to make ’em,” Ben-Hur is an example of how Hollywood use to make them: big and large and visually riveting by virtue of its scope.

It’s worth bearing in mind when seeing Ben-Hur that there are no computers used here. What is on screen is what was on the set, including the great chariot race.

20 Movies: Hero (Ying xiong) (2002)

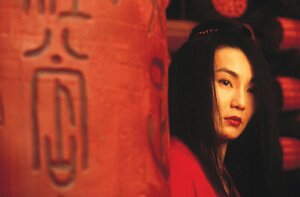

It seems appropriate that a movie that is mythic and fantastic should also be fantastic, not in the fantasy sense but in the Wow! sense. To a degree, the story is irrelevant here because the movie is so visually stunning, partly due to the acrobatic swordplay scenes but primarily through the use of colour and staging of scenes.

But there is more to Hero than its look. At its heart, it is romantic. It’s romantic in its view of China’s history and it’s romantic in the relationships between characters. As story ingredients go, there are few things as engaging as romance.

Hero (Ying xiong) (2002)

Hero (Ying xiong) (2002)

directed by Yimou Zhang

With a movie as good as Hero, where do you begin? There are so many elements, so many perspectives, so many levels that warrant lengthy discussion it’s almost impossible to start.

So I’ll begin by first saying my knowledge of China, it’s history and culture and everything else, could be put on the head of pin and still leave room. My ignorance is boundless so anything I have to say comes from a totally western perspective.

But that’s okay because, like any worthwhile art, Hero is a movie for everyone and likely becomes more interesting as more perspectives and interpretations are brought to it.

Set roughly 2,000 years ago in China, Hero is about the beginning of China’s unification as a single nation under the harsh leadership of the King of Qin (played by Daoming Chen).

As mentioned, I know nothing of China but my guess is that Hero is a little bit of history, a little bit of legend and a fairly loose interpretation of both.

As mentioned, I know nothing of China but my guess is that Hero is a little bit of history, a little bit of legend and a fairly loose interpretation of both.

The king has his enemies and the movie begins with a man called Nameless (Jet Li) coming to the emperor to say he has destroyed his three greatest enemies: Sky (Donnie Yen), Broken Sword (Tony Leung Chiu Wai) and Flying Snow (Maggie Cheung). Nameless, in the emperor’s court, tells the king of how he killed these three.

While comparisons have been made between Hero and Akira Kurosawa’s Rashoman, this is a bit misleading. They are similar, however, to the extent that Hero tells the story of the three enemies and their ruin from different perspectives (including the king’s) and not necessarily truthfully. (As Yunda Eddie Feng at suggests, a better comparison might be to The Usual Suspects.)

The film, then, moves inexorably toward its truth and this is where the film’s title, Hero, becomes interesting. Who is the hero? There appear to be several.

The film, then, moves inexorably toward its truth and this is where the film’s title, Hero, becomes interesting. Who is the hero? There appear to be several.

I understand that ying xiong doesn’t distinguish between singular and plural (as we do with the English hero and heroes). I don’t know, but it is certainly one of the interesting aspects of the film – what is a hero and what makes him or her heroic?

In the movie, despite it’s Hong Kong martial arts and swordplay, the implicit violence of swords is downplayed.

One of the film’s keys is the idea of swordsmanship and calligraphy being connected. Calligraphy is a hugely important element of the film.

One of the film’s keys is the idea of swordsmanship and calligraphy being connected. Calligraphy is a hugely important element of the film.

The movie overall is lyrical, even poetic. Similar to Ang Lee’s approach in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, the film is more interested in the romance of its story than in any other element. It’s from this romance the lyricism is drawn and it is what unifies the entire film.

And while there is romance of the love variety, the greater romance is in the view of heroism – sacrifice and honour.

For me, the best martial arts films are like the best westerns. In fact, I think they are essentially the same genres but from different (though dovetailing) cultures.

Both are at their best when informed by morality and romance. I would argue (and have argued) that these two genres (martial arts and westerns) are the same, and are essentially romantic, moral tales given a deceptive high adventure gloss.

Both are at their best when informed by morality and romance. I would argue (and have argued) that these two genres (martial arts and westerns) are the same, and are essentially romantic, moral tales given a deceptive high adventure gloss.

From my admittedly limited perspective, what Hero most reminds me of are the great films of Sergio Leone like The Good, The Bad and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West. It’s not just in the type of story but also the way it is told.

Like Leone’s films, I can’t image Hero in anything but widescreen. The cinematography of Christopher Doyle is breathtaking.

The way scenes are framed, spread across the screen, elements juxtaposed, gives the movie its epic and legendary look.

And while I see many movies use colour (usually in an annoying way), in Hero colour literally tells the story.

And while I see many movies use colour (usually in an annoying way), in Hero colour literally tells the story.

Working in tandem with the wonderful music of Tan Dun, the story gets told almost without the necessity of words.

Hero isn’t just a good movie, it’s a great movie. It’s epic and rich and a veritable visual feast … even if, like me, you know next to nothing about China.

See: 20 Movies – The List

Hero (the trailer):