I watched Sullivan’s Travels (1941) yet again last night because, as the main character John L. Lloyd ‘Sully’ Sullivan (Joel McCrea) says:

“There’s a lot to be said for making people laugh. Did you know that’s all some people have? It isn’t much, but it’s better than nothing in this cockeyed caravan.”

The words, of course, are from Preston Sturges, writer and director of the movie. This movie is, for me, the best of Sturges — though it’s really hard to say one is better than another when you consider movies like The Lady Eve, The Miracle at Morgan’s Creek and others.

If you’ve ever seen the Coen Brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou? you may be interested in knowing Sullivan’s Travels is where that title came from. It’s the movie Sullivan, a Hollywood director of light, comedic fluff, a man with a well-to-do, somewhat privileged background, wants to make. It’s to be a serious movie about how tough and awful this life is with, “…Bodies piling up in the street.” It’s to be, “A true canvas of the suffering of humanity!”

As his producers point out, what would he know about it? Realizing the truth in what they say, he sets off to find out, decked out like a tramp (from the wardrobe department) and with only ten cents in his pocket.

Unfortunately for Sullivan, despite his best efforts he keeps ending up in Hollywood.

In the third act, however, when he has finally given up his quest, that’s when he actually stumbles into the “trouble” he’s been trying to discover.

A plot summary does little to communicate why this movie is so good.

To begin with, it’s incredibly funny with the humour finding two sources: visual (slapstick) and verbal (witty dialogue). For slapstick, see the chase scene with the kid driving the rigged up “go-cart.” For dialogue, see the scene near the beginning where Sullivan argues for his idea with the producers (“But with a little sex!”).

While very funny (and a romance to boot, with Veronica Lake), it’s a satire of movie makers, particularly of the Hollywood variety. Some even argue that Sullivan’s Travels is the best movie ever about making movies. I think, however, Sturges’ satire goes beyond movies to culture overall.

His complaint is that comedy, and fluff generally, gets dismissed because, being light and agreeable when well done, it isn’t serious, or what we consider to be serious. A history of comedy at the Oscars gives credence to his complaint. It’s ignored when it comes to the “serious” categories like Best Picture.

I think his argument is two-fold: 1) audiences, on the whole, prefer lighter films — comedy, action, etc., and 2) the people who make the serious ones about such topics as homelessness, have no idea, no experience, no real understanding of what they are making a movie about. For one thing, the very people those films are sympathetic to, and that they stand morally side by side with, are the very people they show disrespect to by dismissing the kinds of films they like.

There’s a fabulous speech prior to Sullivan heading out to “learn something about trouble,” meaning homelessness. It’s made by Robert Greig as Sullivan’s butler Burroughs. He says he doesn’t think the plan is a good one because Sullivan has no clue about what poverty is: it’s not some romantic condition to be discovered but something virulent to be avoided. I think this is Sturges saying there is often a patronizing, even parasitic element to serious films and the subjects they treat. That’s probably far too extreme a view, but I think there is an element of truth in it. It makes for an interesting question though: can something not truly lived, something only experienced in a kind of vacation mode, meaning briefly, truly be understood? How often do we bring our assumptions about what something is, assumptions that come from a very different perspective, into our assessments and treatments, such as a in a film?

Of course, the movie doesn’t come across as pontificating, as the above makes it sound. It’s great fun, incredibly funny and with a beautiful Veronica Lake, romantic too. And even if the overall sentiment and the closing lines sound a bit cornball to us, I think it’s a legitimate view and never more passionately expressed as in Sullivan’s Travels.

I’ll have to watch the Coen’s O Brother, Where Art Thou? again because I’m now wondering if they were not only agreeing with Sturges and his argument in comedy’s favour but doing so by making Sullivan’s intended movie, one about a serious subject as done by a patronizing, uninformed fool? My guess is yes.

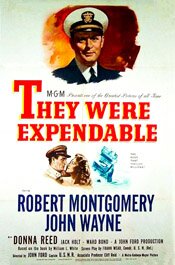

They Were Expendable (1945)

They Were Expendable (1945)