Among the many fascinating and, in this case, amazing things about The Maltese Falcon is that it was the first film for Sydney Greenstreet who was 62 years old at the time. Can you imagine any actor today getting a role, much less starting a career at 62?

High Sierra: When the bad guy is the good guy

I recently finished reading Stefan Kanfer’s Tough Without a Gun: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of Humphrey Bogart. (The title is from something Raymond Chandler said of Bogart.) So of course, I’m back to watching Bogart movies, at least for the time being.

Film noir doesn’t always mean good: Dark Passage

It’s Day 6 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. And if you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down this page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

As much as I like movies in the film noir category, particularly those from the forties and fifties, the term is not a synonym for good. As with any type of movie — screwball, romance, western, drama — it has its clunkers.

Of course, everything is subjective. As you’ll read below, I don’t have a high opinion of Dark Passage. Maybe the problem isn’t the movie but me. To be fair, there is this review over at Noir of the Week. As for mine …

Dark Passage (1947)

Dark Passage (1947)

Directed by Delmer Daves

Of the four movies Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall made together, Dark Passage is easily the weakest. (Their other movies together were To Have and Have Not, The Big Sleep, and Key Largo.) It’s a film noir that has what it thinks is a neat idea — the first third of the movie uses a “first-person” camera, meaning the central character is the camera viewpoint.

But it falls flat.

In fact, the gimmick pretty much ruins the film because we don’t get to see (and therefore connect with) Humphrey Bogart’s character. In the first third, we don’t see him period. He is the camera viewpoint. In the second third, his head is bandaged (due to plastic surgery to alter his identity).

We don’t actually see Bogie till a large chunk of the movie is over. By the time we do, we’re bored.

Bogart plays a character wrongly accused and convicted of murder. The movie opens with his escape. On the run, he is rescued by Lauren Bacall’s character. (Everyone Bogart runs into in the movie conveniently has some connection to the story.)

Bogart plays a character wrongly accused and convicted of murder. The movie opens with his escape. On the run, he is rescued by Lauren Bacall’s character. (Everyone Bogart runs into in the movie conveniently has some connection to the story.)

A helpful cab driver later recommends a shady plastic surgeon to Bogart’s character. Bogart gets his face changed then goes off in search of the criminals who framed him so he can prove his innocence.

Despite trying, the movie never gets very interesting. For one thing, there is very little to relieve the darkness of the noir approach. There is also little chemistry between Bogart and Bacall and this is largely because they play so few scenes together, at least in the first two thirds.

The characters do have scenes, but since Bogart isn’t physically in them (because of the camera viewpoint or because his head is wrapped in bandages and he can’t talk), the Bogie-Bacall magic is absent.

The other problem are the improbable conveniences mentioned above — the helpful cab driver, a guy who picks up Bogart when he is hitchhiking, Bacall’s appearance. It’s all a little too improbable.

The other problem are the improbable conveniences mentioned above — the helpful cab driver, a guy who picks up Bogart when he is hitchhiking, Bacall’s appearance. It’s all a little too improbable.

The only time we get a sense for an interesting story is at the very end when Bogart and Bacall have fled to South America. Suddenly the heavy handed noir atmosphere is relieved and we get something that has more of the atmosphere of Casablanca or To Have and Have Not.

It seems clear that the movie has misread what made Bogart and Bacall so interesting together. It certainly misreads Bogart.

Despite the success of movies like The Big Sleep and The Maltese Falcon, it wasn’t the noir genre that made Bogart popular. It was that he was playing a flawed romantic hero within them.

Despite the success of movies like The Big Sleep and The Maltese Falcon, it wasn’t the noir genre that made Bogart popular. It was that he was playing a flawed romantic hero within them.

In Dark Passage he simply plays a schmuck floundering around trying to prove his innocence. He doesn’t play a strong character. If anything, the character is rather weak.

And so we end up with a tedious movie, one that relies on a gimmick rather than the power Bogart and Bacall could bring to the screen.

They are wasted in this movie.

On Amazon:

- Dark Passage

- Bogie and Bacall – The Signature Collection (includes: The Big Sleep, Dark Passage, Key Largo and To Have and Have Not)

Key Largo: truly an ensemble movie

After The Big Sleep, John Huston’s Key Largo is my favourite Bogie and Bacall movie. Another good one is To Have And Have Not and the fourth would be Dark Passage, the weakest of them all because it is so wrong-headed.

Key Largo is partly interesting because the famous Bogie-Bacall chemistry is pretty much irrelevant. It may be there, but so what? This movie is about the story, the drama and all the characters. I think we can thank John Huston for that.

Key Largo (1948)

Key Largo (1948)

Directed by John Huston

Of the four movies Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall made together, Key Largo is the last. What strikes me as interesting about it is how, despite the romance suggested between the characters, Bacall is almost a minor character in the movie. But then, in a sense, so are all the characters.

This is truly an ensemble movie, perhaps because it began as a play. You might expect it to focus on Bogart and Bacall, especially given their fame as a couple, but it doesn’t.

Director (and co-writer) John Huston is more interested in the story.

As the movie plays out, the film seems to hand the lead role off from Bogart, then to Robinson, then to Barrymore, then to Trevor, and then back to Bogart again. At the same time, Huston emphasizes place – in this case, the Florida Keys – as a major character, as he does with the hurricane.

Having left the Army, ex-Major Frank McCloud goes to Key Largo to pay respects to the family of one of the soldiers under his command who was killed in action. McCloud seems a bit aimless having left the army; this obligation he feels to visit the family is about the only purpose he has at this stage in his life.

Having left the Army, ex-Major Frank McCloud goes to Key Largo to pay respects to the family of one of the soldiers under his command who was killed in action. McCloud seems a bit aimless having left the army; this obligation he feels to visit the family is about the only purpose he has at this stage in his life.

The family owns a hotel in Key Largo and when McCloud gets there both he (and we, the audience) sense something is up. Some shady characters are hanging around the hotel and they seem eager for McCloud to leave.

As the movie unfolds, it turns out they are criminals. They take over the hotel as they await other criminals to meet up with them in order to conclude a deal concerning counterfeit money. It also turns out they are led by Johnny Rocco (Edward G. Robinson) who has returned to reclaim his life and position in the criminal world, from which he has been gone for eight years (likely in prison).

Unfortunately for the gang of thugs, this is Florida and it is hurricane season and one is blowing in.

What the movie does is to bring all these characters together in one place and confine them in close quarters. You feel the walls closing in, so to speak, as the winds get stronger and shutters are closed. They are all closed in; sunlight vanishes.

What the movie does is to bring all these characters together in one place and confine them in close quarters. You feel the walls closing in, so to speak, as the winds get stronger and shutters are closed. They are all closed in; sunlight vanishes.

The movie’s true is star is arguably Edward G. Robinson. He’s mean and menacing and dominates everything around him. Once he appears in the movie (which is not immediate), he seldom leaves the frame.

There is a curious contrast between Robinson’s Johnny Rocco and the other characters. In many ways, they are all frozen in the moment, unsure what to do (except Rocco). Because of the death of Bacall’s husband, who is also Barrymore’s son, those two are stuck. McCloud, discharged from the Army, is unsure what to do with his life. They would all like to go forward; they’re just not sure how.

But Johnny Rocco has no interest in going forward. He wants to go back. He wants to reclaim and relive his former glory. He lives in, and dreams of, the past. Claire Trevor’s character, Gaye Dawn, is also stuck in the past because she is still connected with Rocco and she is an alcoholic. The relationship is abusive but she is dependent on Rocco, or so she feels. She is stuck and, because of her association with Rocco, it is the past she is stuck in.

Just as they are all confined within the hotel, so they are confined within this moment of uncertainty about their lives. They aren’t living in the present; they are confined within it.

Tension builds in the movie partly because of the storm, partly because Johnny Rocco gets increasingly anxious about completing his deal, but also because of the forward and backward pull between the characters: Johnny’s will to go back to the past; McCloud and the others’ desire to break free and go forward into the future.

Tension builds in the movie partly because of the storm, partly because Johnny Rocco gets increasingly anxious about completing his deal, but also because of the forward and backward pull between the characters: Johnny’s will to go back to the past; McCloud and the others’ desire to break free and go forward into the future.

Dramatic and suspenseful, Key Largo is a tremendous example not just of good filmmaking but of good drama, period. It’s a good story well told. I loved it.

On Amazon:

- Key Largo (DVD) — Amazon.com (U.S.)

- Key Largo (DVD) — Amazon.ca (Canada)

How Chandler’s Marlowe is like Hamlet

Inexplicably, after what seems a kind of cinematic hiatus, I’m watching a bevy of older films and, to the dismay of some, rambling on paper (or screen, to be more accurate) my dimly lit opinions of what I’m seeing. I seem to be bouncing back and forth between noir and romantic comedies. The only thing I can venture as at least an explanation in part is this: I find watching movies relaxing, even meditative in some way. I don’t get this watching TV; only movies.

The other day, it was yet another noir …

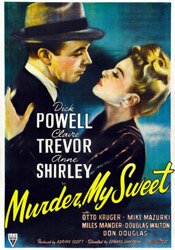

Murder, My Sweet (1944)

Murder, My Sweet (1944)

Directed by Edward Dmytryk

This murder mystery is, for me, itself a mystery in that I cannot fathom why they would change the title of Raymond Chandler’s book, Farewell, My Lovely to the far less subtle, Murder, My Sweet. I know it had something to do with not wanting to confuse the public with lead actor Dick Powell’s previous roles as a kind of song and dance man, but that doesn’t seem a very credible reason to me.

I suppose it’s not very important in the larger scheme of things, but it makes me shake my head. As for the movie …

When you go over reviews of this movie, as well as other movies based on Chandler’s books, you see one topic continually pop up: who was the best Philip Marlowe? It is probably not surprising to find there is not a great deal of consensus.

It strikes me that Marlowe is a kind of variation on Hamlet in that everyone has to play him, or a variation on him, and we decide who does it well, who doesn’t, and who’s Marlowe we buy into. On the DVD case cover, it tells us Dick Powell, who plays Marlowe in Murder, My Sweet, was author Raymond Chandler’s favourite. Of course, others have different opinions. Bogie comes to mind.

For many people Humphrey Bogart (The Big Sleep) is the Philip Marlowe. But just today I came across a review where the writer was claiming the best Marlowe was Robert Mitchum in 1975’s Farewell, My Lovely.

For many people Humphrey Bogart (The Big Sleep) is the Philip Marlowe. But just today I came across a review where the writer was claiming the best Marlowe was Robert Mitchum in 1975’s Farewell, My Lovely.

I admit that when I first saw Murder, My Sweet a few years ago Powell bothered me, but that had less to do with his performance than the fact I had Bogie so drilled into my head, from The Big Sleep but also similar characters, like Sam Spade from the The Maltese Falcon.

But I watched Murder, My Sweet again last night and I liked Powell much more. His gestures and speech fit the character nicely and he seems very natural as Marlowe. And the more I think about it, the more I think, “Yes, I like Powell’s Marlowe.” (That’s sort of like saying, “I like Plummer’s Hamlet.”)

As for the movie as a movie … It has a lot of what you would expect from a film of this kind: a lot of uncertainty as characters appear to be good, then bad, then good again, and then bad once more. Marlowe seems to think one thing then it’s shown he was only pretending, although a later scene shows he actually does think and feel that way.

In other words, the movie twists quite a bit and in many cases the twists are arbitrary for the sake of being a twist and to sustain the mood. But they don’t make a lot of sense. Yet in a film noir, you can often get away with that because the movie is less about plot and more about atmosphere, characters, character relationships … and lighting and camera focus.

In other words, the movie twists quite a bit and in many cases the twists are arbitrary for the sake of being a twist and to sustain the mood. But they don’t make a lot of sense. Yet in a film noir, you can often get away with that because the movie is less about plot and more about atmosphere, characters, character relationships … and lighting and camera focus.

I’ve read the book this movie is based on but don’t recall it, so I can only assume the movie stays roughly true to it and, if that’s he case, the filmmakers can thank Chandler for writing them an opening that is a nicely baited hook.

Told almost entirely in flashback by Marlowe, it begins with him in a police station being questioned and telling his story. That wouldn’t be much except we’re shown that he can’t see; his eyes are completely bandaged up. So as he’s is grilled and finally starts telling his story, we’re already hooked on the mystery of what happened to his eyes even before we’ve had an inkling of the real mystery.

Being film noir, we also get a femme fatale. Claire Trevor is Mrs. Helen Grayle, aka Velma. Director Edward Dmytryk introduces her to us legs first, underlining the character’s sexual nature and involvement with the story. But the there is also Anne Shirley as Ann Grayle, step-daughter and enemy of the second Mrs. Grayle (Velma). It’s easy to see why.

Being film noir, we also get a femme fatale. Claire Trevor is Mrs. Helen Grayle, aka Velma. Director Edward Dmytryk introduces her to us legs first, underlining the character’s sexual nature and involvement with the story. But the there is also Anne Shirley as Ann Grayle, step-daughter and enemy of the second Mrs. Grayle (Velma). It’s easy to see why.

Ann Grayle loves her father (Miles Mander), who is much older than his new wife. He also seems frail by comparison to everyone else in the film, even impotent. And he’s married to a woman who doesn’t appear to cover up what she’s interested in:

Helen Grayle: I find men very attractive.

Philip Marlowe: I imagine they meet you halfway.

But the movie isn’t just about this. It begins with a man named Moose (Mike Mazurki), who is just out of jail and looking for his Velma.

But the movie isn’t just about this. It begins with a man named Moose (Mike Mazurki), who is just out of jail and looking for his Velma.

Chandler books, and movies of this variety, are peppered with characters, most of whom are types, and give the storyline places to go and people to engage with as well as scenes to play out before getting to an end.

I liked how this one plays out. I like Dick Powell as Philip Marlowe and Claire Trevor as a femme fatale. And I’m pretty sure I’ll be watching this one again.

Dark Passage: a waste of Bogie and Bacall?

I just did some housecleaning on Piddleville. I more or less cleaned up some code and design on a few reviews that were in a very old Piddleville format.

While doing so, I came across a few Bogie and Bacall movies, including 1947’s Dark Passage which, as it turns out, I apparently didn’t care for. Here’s the review:

Dark Passage

Directed by Delmer Daves

Of the four movies Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall made together, Dark Passage is easily the weakest. (Their other movies together were To Have and Have Not, The Big Sleep, and Key Largo.) It’s a film noir that has what it thinks is a neat idea — the first third of the movie uses a “first-person” camera, meaning the central character is the camera viewpoint. But it falls flat.

Of the four movies Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall made together, Dark Passage is easily the weakest. (Their other movies together were To Have and Have Not, The Big Sleep, and Key Largo.) It’s a film noir that has what it thinks is a neat idea — the first third of the movie uses a “first-person” camera, meaning the central character is the camera viewpoint. But it falls flat.

In fact, the gimmick pretty much ruins the film because we don’t get to see (and therefore connect with) Humphrey Bogart’s character. In the first third, we don’t see him period. He is the camera viewpoint. In the second third, his head is bandaged (due to plastic surgery to alter his identity).

We don’t actually see Bogie till a large chunk of the movie is over. By the time we do, we’re bored.

Bogart plays a character wrongly accused and convicted of murder. The movie opens with his escape. On the run, he is rescued by Lauren Bacall’s character. (Everyone Bogart runs into in the movie conveniently has some connection to the story.)

Bogart plays a character wrongly accused and convicted of murder. The movie opens with his escape. On the run, he is rescued by Lauren Bacall’s character. (Everyone Bogart runs into in the movie conveniently has some connection to the story.)

A helpful cab driver later recommends a shady plastic surgeon to Bogart’s character. Bogart gets his face changed then goes off in search of the criminals who framed him so he can prove his innocence.

Despite trying, the movie never gets very interesting. For one thing, there is very little to relieve the darkness of the noir approach. There is also little chemistry between Bogart and Bacall and this is largely because they play so few scenes together, at least in the first two thirds.

The characters do have scenes, but since Bogart isn’t physically in them (because of the camera viewpoint or because his head is wrapped in bandages and he can’t talk), the Bogie-Bacall magic is absent.

The other problem are the improbable conveniences mentioned above — the helpful cab driver, a guy who picks up Bogart when he is hitchhiking, Bacall’s appearance. It’s all a little too improbable.

The only time we get a sense for an interesting story is at the very end when Bogart and Bacall have fled to South America. Suddenly the heavy handed noir atmosphere is relieved and we get something that has more of the atmosphere of Casablanca or To Have and Have Not.

It seems clear that the movie has misread what made Bogart and Bacall so interesting together. It certainly misreads Bogart.

Despite the success of movies like The Big Sleep and The Maltese Falcon, it wasn’t the noir genre that made Bogart popular. It was that he was playing a flawed romantic hero within them.

In Dark Passage he simply plays a schmuck floundering around trying to prove his innocence. He doesn’t play a strong character. If anything, the character is rather weak.

And so we end up with a tedious movie, one that relies on a gimmick rather than the power Bogart and Bacall could bring to the screen.

They are wasted in this movie.

On Amazon:

- Dark Passage

- Bogie and Bacall – The Signature Collection (includes: The Big Sleep, Dark Passage, Key Largo and To Have and Have Not)

Finally, The African Queen

I saw on the TCM home page something that caught my eye: (1951) being released on March 23, 2010 in a “Commemorative Box Set.” I care less about the box set business than I do about this note (found in the information on Amazon): “Fully Restored using state-of-the-art restoration process.”

I have been waiting forever to get a decent copy of this movie on DVD. You would think this would have been one of the movies that had been released as a DVD long ago — and released several times over. But that has not been the case. I believe rights problems may have made a mess of things (if I recall correctly). Maybe it was public domain? I no longer remember.

The point, however, is that it is finally coming, if a little pricey because it’s a box set. On the other hand, I find what is included intriguing. Amazon lists the special features as:

– Fully Restored using state-of-the-art restoration process

– Includes all-new hour long “making of” feature with never-before-seen images and commentary

– Collectible packaging highlighting Humphrey Bogart and Katharine Hepburn

– Second disc with the original Lux radio broadcast of The African Queen starring Humphrey Bogart and Greer Garson (Audio CD)

– Reproduction of Katharine Hepburn’s out-of-print published memoir: The Making of The African Queen or How I Went to Africa with Bogart, Bacall and Huston and Almost Lost My Mind

– Collectible Senitype®: a four film frame card illustrating the Technicolor® process

– 8 images inspired by original theatrical lobby cards

The release date is March 23. And apparently there will be a Blu-Ray version too. I am waiting.