I’ve twice seen the 1953 movie Dream Wife recently and have twice had the same the same response. It just isn’t a very good movie. Even stars like Cary Grant and Deborah Kerr can’t save it, though they do make it more palatable.

Playing it straight: The Lady Eve

I foolishly put a poll on Facebook asking people what movie they felt was Preston Sturges’ best. It was foolish because I used the word “best” when I should have used “favourite” or some other word. How can you pick a “best” Sturges when there are a fistful of movies that could vie for the top with legitimacy? However … as it turns out, though a very small sampling, tied at the top of the results were Sullivan’s Travels and …

Continue reading

Easy Living (1937): Everybody fall down

When a an expensive fur coat falls on her head, Mary Smith’s life of scraping together enough for food and rent turns upside down. She suddenly finds herself in a world of wealth, as she’s mistakenly perceived of as the mistress of Wall Street banker and tycoon, J.B. Ball.

Easy living was never so hard — or muddled and funny.

Lily Damita, Roland Young and This is the Night

Without intending to, I caught This is the Night on TCM last night and I was delightfully surprised. It was funny, curious and also interesting historically in that it was the first full feature movie Cary Grant ever appeared in. It was directed by Frank Tuttle, a man I know best for having directed This Gun For Hire that starred Veronica Lake.

This is the Night (1932)

This is the Night (1932)

Directed by Frank Tuttle

To get the Cary Grant aspect out of the way, you can tell it’s an initial effort. His performance is good sporadically. Often he overplays it, though in one way it works because the film is a farce. You can see, however, the beginnings of what he would later become, especially his comedic skills.

But this movie is really Lily Damita’s and Roland Young’s. (The movie also stars Charles Ruggles and Thelma Todd.)

An athlete (Grant) returns from the Olympics. While he was away, his wife (Todd) has been involved with another man. As that other man, Roland Young must try to cover up the affair. With the help of a friend, Ruggles, he hires a heavily accented actress (Damita) to pretend she’s his wife.

It’s a relationship comedy – quite a funny one – and it is filled with sexual jokes. (The movie was made pre-Code.) For example, a recurring joke in the movie involves Todd whose dress keeps getting removed accidently by the chauffeur/butler. There are verbal jokes as well, such as Damita’s character who doesn’t understand English well, and ends up interpreting hints as, “I live in sin. I am naughty,” when Young tries to tell her to say she’s from Cincinnati.

It’s silly, yes, but lots of fun. It’s not exactly a screwball comedy; it’s a bit too farcical for that. But you can see the beginnings of screwball (just as you can see lingering hints of the silent era in the visual humour, as mentioned in this review).

What I found curious, and a little off-putting, was what I initially thought was a technical mistake in the broadcast but later saw was deliberate. It was this: much of the film occurs in Venice and much of that is at night. Every time the action occurs outside, at night, the screen goes blue.

Yes, it’s a colour that suggests night but in a movie that is otherwise black and white it’s a jarring and unnecessary effect. A quick online look revealed no reference to this so I don’t know if this was something the original movie tried or was added later. But I do know I would remove the effect.

Apart from that, This is the Night is a very fun and funny movie; it even has some nice romantic elements, not to mention Cary Grant’s movie debut. I was glad I found it.

As an aside, Cary Grant would work with Roland Young again a few years later in the movie Topper (1937).

As another aside, Lily Damita was married to Errol Flynn for a number of years and later married to Michael Curtiz. Her Hollywood career was relatively brief. She essentially got out of acting in movies when she married Flynn.

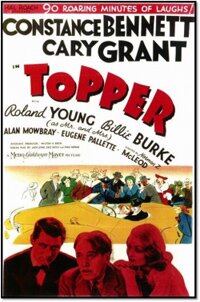

20 Movies: Topper (1937)

This was a movie I knew absolutely nothing about when I picked it up. I watched it and found it was one of the funniest movies I had seen in ages. This surprised me because of its age. There are a lot of movies that amuse me but not many that actually make me laugh.

Comedy, of course, is a pretty subjective thing and what I find funny may not be shared by someone else. Still, it’s hard for me to imagine someone not laughing when they see Roland Young comes down those hotel stairs with ghostly assistance.

Topper (1937)

Topper (1937)

directed by Norman Z. McLeod

Fun, light and funny, the movie Topper is a delightful screwball comedy. It shares the style of, and comes a year or two after, the classic My Man Godfrey. Though not as good as that film, it excels in many ways, not the least of which is a very good cast.

While Cary Grant is in it (and playing an earlier version of a comedic type he would use later in His Girl Friday -– a self-involved man with the proverbial “heart of gold”), the real star is Constance Bennett.

The female lead in screwball comedies, like Carole Lombard in My Man Godfrey, is usually wealthy and ditzy (though not unintelligent). She’s generally completely unconcerned with everything around her except for whatever her wandering imagination has focused on. In the case of Topper, Bennett plays this role though it’s complemented by Grant, as her husband, who is equally wealthy and ditzy.

In contrast to this, there is always the serious role – in this case Corso Topper, played by Roland Young. He’s a banker – dull, pining for a more exciting life, and under his wife’s thumb (played by Billie Burke – Glinda, the Good Witch of the North in The Wizard of Oz).

It’s a traditional contrast – trickster characters (Bennett, Grant) and the dull oaf that needs to lighten up (a bit like Malvolio in Twelfth Night).

It’s a traditional contrast – trickster characters (Bennett, Grant) and the dull oaf that needs to lighten up (a bit like Malvolio in Twelfth Night).

The conceit behind Topper is that the wealthy couple George and Marion Kirby are killed in a car accident (caused by Grant’s fun-loving foolishness). They become ghosts. As such, they determine they are stuck on earth, unable to move on to Heaven, until they have done a good deed. They decide Topper will be their good deed. They will take him out of his formal, proper shell and introduce him to life.

And so the fun begins.

There are a lot of wonderful moments in the film, including numerous sexually suggestive jokes that would likely not be allowed in later years. They are not overt, brazen moments (as you would likely get today), but deliciously suggestive – making them funnier and more sexy. Bennett plays her role with delightful coyness and flirtatiousness. The interaction with Roland Young as the hide-bound banker is great fun to watch.

(It’s a bit surprising some of this got past the Hays Code.)

In Topper, you get to see Corso Topper come out of his shell and develop into the man he wants to be. (One of the best scenes, howlingly funny, is a drunk Topper being helped down stairs through a hotel lobby by invisible ghosts.)

In Topper, you get to see Corso Topper come out of his shell and develop into the man he wants to be. (One of the best scenes, howlingly funny, is a drunk Topper being helped down stairs through a hotel lobby by invisible ghosts.)

You also see his wife develop from icy social climber to a more loving woman.

Screwball comedies are one of my favourite kinds of movies and Topper is a wonderful example of the genre. Recommended.

See: 20 Movies — The List

20 Movies: His Girl Friday (1940)

I’ve always liked Howard Hawks and this movie, His Girl Friday, is one of my favourites from his long list of films. Apart from being a famously funny movie, it’s known for the incredibly rapid fire dialogue between Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell.

His Girl Friday (1940)

directed by Howard Hawks

It occurs to me that the best movies are one of two types. They are visually compelling, like the recent Hero, where there almost seems to be no need for dialogue. The images communicate almost everything.

Or, the movie relies heavily on great dialogue, the kind that is fun to hear and is engaging, and reveals everything about the characters.

A movie like 1995’s Get Shorty is a good example.

An older and better example, from 1940, is His Girl Friday, directed by Howard Hawks and starring Cary Grant and Rosalind Russell. It’s correctly considered a classic with its rapid fire dialogue and frenetic pace.

Based on the play The Front Page, director Hawks had his screenwriter Charles Lederer make some changes. The biggest change was to make one of the two main characters, Hildy Johnson, a woman (played by Russell) – the ex-wife of editor Walter Burns (Grant).

This created an added dimension to the dynamic of two newspaper people – one wanting to leave the business (Johnson) and the other trying to get her to stay.

It was no longer just a struggle between editor and reporter; it was a battle of the sexes, which Hawks loved putting on film.

Hildy is not only leaving the newspaper business; she’s engaged to be married the next day to her new beau, Bruce Baldwin (Ralph Bellamy), a rather dull insurance guy. He’s the complete opposite of Grant’s flamboyant (and not to be trusted) Walter.

And Walter is determined to get Hildy back – both as his wife and as his reporter. He determines to do this by appealing to the journalist in her. Through guile and deceit, he’s going to try to hook her like a fish and reel her in. Fortunately for him, there is an execution scheduled at the prison of convicted murderer Earl Williams (John Qualen) who, Walter casually mentions to Hildy, may be innocent.

Being based on a play, His Girl Friday only has about three sets and, with the exception of the opening which uses a moving camera, most shots are static, the scenes occurring in sets where characters enter and leave like a train station platform.

But given the simplicity of the sets and the static nature of the cameras, it’s really quite amazing how fast everything is and how much energy is generated.

What’s marvellous about watching the give and take between Grant and Russell, apart from the speed, the quick witted lines and great, comic takes (particularly by Grant) is how, as we see them battle, we also see how clearly they are suited for each other and meant to be together.

Ralph Bellamy’s Bruce never has a chance.

65 years later, His Girl Friday still stands up. It’s as fast and funny today as it was then.

And with the world of recent comedies, it’s something of a relief to see characters who are smart and a film that can make us laugh without dropping its pants.

(This review was written around 2002-2003.)

See: 20 Movies – The List

Leopards and actors and Cary Grant

I rewatched for the nth time (I’ve lost track) Howard Hawk’s Bringing Up Baby (1938). Apart from being great fun each time I watch it, this time was a bit different having read Marc Eliot’s book, Cary Grant: A Biography, and having previously watched Cary Grant: A Class Apart (a documentary on the second disc of the two-disc special edition DVD).

Here’s why this is interesting: Seeing Bringing Up Baby, at least as I do, you would think Cary Grant is in full command of what he’s doing — the ever skillful and brilliant, Cary. However, what you find out is that that is anything but the case.

Grant had had huge success with the previous year’s The Awful Truth (1937). However, he never took credit for its success because he had no idea how he had done it. He felt it was a fluke. He had been extremely anxious over his character, not sure how to play him, copying many mannerisms and stances of his then director, Leo McCarey.

Following closely on The Awful Truth, he was worried again about how to play his character in Bringing Up Baby and, compounding this, “… he was afraid to make a movie that was too stylistically similar in which his performance would not be as good.” (From Eliot’s biography of Cary Grant, p. 178.)

“Hawks then suggested to Grant that he look at some of the films of Harold Lloyd. Grant did and was so taken with the comedian’s style of acting that he actually copied it, almost gesture for gesture, in putting together his interpretation of David Huxley, down to the thick horn-rimmed glasses, one of Lloyd’s cinematic trademarks.” (Eliot’s biography of Cary Grant, p. 178.)

Still, while his template may have been Harold Lloyd what ends up on screen is pure Cary Grant, albeit with a Lloyd influence and the Cary Grant of a certain period of his career (younger, pre-Hitchcock etc.).

Of course, background isn’t necessary to enjoying this comedy classic. It may even get in the way until you’ve seen it a few times. It’s one of the great screwball comedies, peppered with absurdities and the better for it.

For what it’s worth, here’s the assessment I wrote a while back of Bring Up Baby (the two-disc special DVD edition).

Two men, one Hitchcock

I recently finished reading Marc Eliot’s Jimmy Stewart: A Biography. Because I was reading it, I also watched a lot of Jimmy Stewart movies, which I’ve posted about before. Now I’m reading (or, rather, re-reading) Eliot’s Cary Grant: A Biography.

In many ways, you couldn’t find two actors more different. For example, one was a pretty straight-laced American, almost a poster child for the 1940s, 1950s middle-America image of what a man should be.

That would be Jimmy Stewart.

The other was bisexual (despite his famous romantic image), had a long term relationship with another well-known male actor, and was British.

That would be Cary Grant.

They had one thing in common though: Alfred Hitchcock. Both actors did some of their best work, if not the best work of their careers, with Hitchcock.

Their differences, however, are likely why Hitchcock used them and in many ways those differences defined how he used them (and why).

Last night I watched North by Northwest and remembered that Jimmy Stewart had wanted to be in the movie (having recently done Rear Window, The Man Who Knew Too Much and Vertigo with Hitchcock) but didn’t get the part – Hitchcock didn’t want him. He wanted Grant. (The director waited to pick his lead until Stewart was involved, and obligated to, Bell, Book and Candle, so he could use that as an excuse for not choosing Stewart, so as to soften the blow – they were friends.)

So in the Hitchcock movies, what is the difference between Stewart and Grant? Why did it make a difference to him? Just a whim?

Nope. Each represents something different, a way Hitchcock wants the audience to relate and think about his lead actor. Put succinctly: Stewart is everyman, Grant is fantasy. Stewart is the guy you relate to as yourself, Grant is the guy you relate to as the man you would like to be. In a way, it’s reality on one hand, image on the other.

Each actor did four movies with Alfred Hitchcock. In both cases, Hitchcock made at least one masterpiece (in my opinion). With Stewart, it was Vertigo. With Grant, it was North by Northwest. The former is a kind of study of men, image and reality, and how the unconscious buggers us up. The latter is a kind of study too except it’s more like a master class in filmmaking, in how to get an audience, hold an audience and make one of the most entertaining movies ever through a masterful plot perfectly executed.

You could say Cary Grant’s character is an everyman in North by Northwest, and on the surface that is true. He certainly is in terms of the story on the page. However, when you cast Cary Grant (which you have to believe was a very deliberate, thought-through choice), you don’t have an everyman. You have Cary Grant, an image even Cary Grant said he couldn’t be. On the other hand, when you cast Jimmy Stewart you’re casting an average guy, a run-of-the-mill schmo, an everyman.

(As a not particularly related aside, Cary Grant and Jimmy Stewart appeared in at least one movie together, 1940’s The Philadelphia Story.)

What Topper meant to Cary Grant

Although the movie Topper, despite it’s summer success in 1937, could hardly be considered a big movie, not in the Hollywood terms we usually speak of, it was a key movie in the career of Cary Grant (and for those people who came to love the movies of Cary Grant) because of what it did.

It was one of the first movies Grant made after he chose to break free of the feudal studio system of Hollywood, which basically dictated what he would appear in and what roles he would have, and became an independent actor.

It was also his first chance to do what he desperately wanted to do: comedy. It was the first chance he had to be something other than a pretty boy in a tuxedo and actually showcase his broader talents. It may also have been one of the first times, if not the first, he worked with a director (Norman McLeod) who used something akin to storyboards. McLeod would show Grant and co-star Constance Bennett sketches to illustrate body position, movements and facial expressions in order to better get across what he was after.

A few years ago I wrote a review of Topper but at that time was unaware of its place in Cary Grant’s personal career history. If I were writing it now, I’m sure it would read considerably differently. But I think the overall assessment would be the same. It goes:

Fun, light and funny, the movie Topper is a delightful screwball comedy. It shares the style of, and comes a year or two after, the classic My Man Godfrey. Though not as good as that film, it excels in many ways, not the least of which is a very good cast … (read more)