Let’s go big; really big. Before the world of CGI, big spectacular stuff had to be done the hard way. (No, I’m not saying CGI is easy.) It had to be done on sets, on location and with real people in the scenes.

Watch Ben-Hur and try to imagine what was involved. Now try to imagine doing that and making a movie that was actually good, one with an interesting story and captivating characters, while you’re also trying to figure out how to manage all the extras, the technical end and all the other hoo-hah that must have gone into this.

It’s really quite remarkable. Ben-Hur is an example of Hollywood doing what Hollywood tends to do, big and bloated, and actually pulling it off.

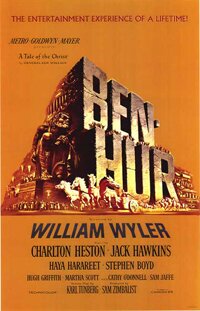

Ben-Hur (1959)

Ben-Hur (1959)

directed by William Wyler

If ever a movie deserved the term “Hollywood spectacle,” it’s 1959’s Ben-Hur from director William Wyler. More than a few dollars went into the making of this one and, to a large extent, you see those dollars on the screen.

Remarkably, it manages to be a pretty good movie too.

Ben-Hur was made in late 50s early 60s period when spectacle was the big thing in for studios. The movies arrived with an air of their own importance, a degree of pomposity that is a little hard to take today. (It may have been hard to handle back then too.)

But Ben-Hur, despite a few slip-ups, largely justifies its pretentious elements.

Like many of those “important” movies of the period, it is quite long. Part of the length is due to beginning the film with an “overture,” an image held on screen for a few minutes while loud and stirring music plays. When finished, they finally start the opening credits.

Later, after a normal film would have concluded, it pauses again a few minutes for the “entre acte,” then proceeds for another hour or so to its finish.

Today, particularly on the home editions of the film, these are historical curiosities that do little else than clog the film.

At the time, they had some purpose but for the most part were elements of the period’s pretentiousness – they served to signal the artistic importance of the movie by suggesting they were to be viewed on the artistic level of opera and symphonies.

The movie itself (subtitled A Tale of the Christ) is drawn from an earlier film (1926’s Ben-Hur) and the original 1880 novel by Lew Wallace.

The movie itself (subtitled A Tale of the Christ) is drawn from an earlier film (1926’s Ben-Hur) and the original 1880 novel by Lew Wallace.

The Christ reference is due to the presence of the life of Christ as part of the story’s background – it occurs at the time of Jesus, who appears as a character a few times in the film and has an influence on Charlton Heston as Judah Ben-Hur.

If you’ve seen Ridley Scott’s Gladiator then you have a good sense for what the story is about. Ben-Hur is a kind of well-off, aristocratic Jew at time they are living under the rule of Rome (the time of Christ). His best friend as a child was a young Roman, Messala (Stephen Boyd). The movie opens with the two boys as men, Messala returning as a Roman legionnaire to rule for Caesar over the Jews.

While still friends who love one another, the division between them of Jew and Roman quickly sets them against each other. Ben-Hur feels compelled to stand up for his people while Messala, somewhat drunk with the power Rome represents, is determined to impose his will on the Jews.

While still friends who love one another, the division between them of Jew and Roman quickly sets them against each other. Ben-Hur feels compelled to stand up for his people while Messala, somewhat drunk with the power Rome represents, is determined to impose his will on the Jews.

The acrimony between them leads Messala to use Ben-Hur as an example. Charges are brought against Ben-Hur and his family which Messala knows to be false. But he sees an opportunity to impose his will be using his friend.

Ben-Hur soon finds himself a prisoner of Rome, banished to the galleys of the Roman fleet.

He spends years as a galley slave until he saves the life of a Roman general, Quintus Arrius (Jack Hawkins), who in gratitude takes him under his wing. Ben-Hur goes to Rome where he races in the arena as a charioteer.

He spends years as a galley slave until he saves the life of a Roman general, Quintus Arrius (Jack Hawkins), who in gratitude takes him under his wing. Ben-Hur goes to Rome where he races in the arena as a charioteer.

He excels and wins honours. Arrius even adopts Ben-Hur as a son.

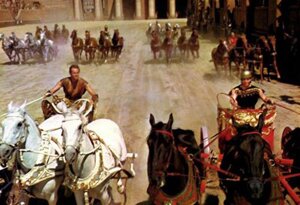

His freedom won, his position secured again, Ben-Hur returns home. He is focused on finding his mother and sister, and getting revenge on Messala. This leads to the great chariot race the movie is famous for, but the movie does not end there.

The final portion of the film is about Ben-Hur finding his family and struggling with his hatred of Messala and Rome within the context of the influence of Christ, particularly Christ’s final days (leading to the crucifixion).

It’s a sprawling story with numerous characters and threads. But by and large it hold together. Wyler manages an enormous task. If nothing else, Ben-Hur is a testimony and tribute to project management (as opposed to the later fiasco, Cleopatra).

It’s a sprawling story with numerous characters and threads. But by and large it hold together. Wyler manages an enormous task. If nothing else, Ben-Hur is a testimony and tribute to project management (as opposed to the later fiasco, Cleopatra).

Being large, it’s many movies at once: an historical costume drama, an action adventure, and a religious film. And each succeeds. Heston is perfect as Ben-Hur. With his granite face, he manages to communicate his character’s simmering rage at the injustice he has suffered.

In fact, the only real flaw in the film is the pretentiousness mentioned earlier. The movie probably could also us some editing to cut down its length but like a novel by Doestoyevsky, in some ways its charm is its lengthy, meandering narrative.

When people speak of movies and say such things as, “…That’s not how they use to make ’em,” Ben-Hur is an example of how Hollywood use to make them: big and large and visually riveting by virtue of its scope.

When people speak of movies and say such things as, “…That’s not how they use to make ’em,” Ben-Hur is an example of how Hollywood use to make them: big and large and visually riveting by virtue of its scope.

It’s worth bearing in mind when seeing Ben-Hur that there are no computers used here. What is on screen is what was on the set, including the great chariot race.