Edward G. Robinson was one helluva a good actor. He even makes this exercise in the absurd and perfunctory a crime drama you can watch, even enjoy at moments. Often found in film noir collections, it isn’t noir. In a way, it’s screwball comedy without the humour.

Key Largo: truly an ensemble movie

After The Big Sleep, John Huston’s Key Largo is my favourite Bogie and Bacall movie. Another good one is To Have And Have Not and the fourth would be Dark Passage, the weakest of them all because it is so wrong-headed.

Key Largo is partly interesting because the famous Bogie-Bacall chemistry is pretty much irrelevant. It may be there, but so what? This movie is about the story, the drama and all the characters. I think we can thank John Huston for that.

Key Largo (1948)

Key Largo (1948)

Directed by John Huston

Of the four movies Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall made together, Key Largo is the last. What strikes me as interesting about it is how, despite the romance suggested between the characters, Bacall is almost a minor character in the movie. But then, in a sense, so are all the characters.

This is truly an ensemble movie, perhaps because it began as a play. You might expect it to focus on Bogart and Bacall, especially given their fame as a couple, but it doesn’t.

Director (and co-writer) John Huston is more interested in the story.

As the movie plays out, the film seems to hand the lead role off from Bogart, then to Robinson, then to Barrymore, then to Trevor, and then back to Bogart again. At the same time, Huston emphasizes place – in this case, the Florida Keys – as a major character, as he does with the hurricane.

Having left the Army, ex-Major Frank McCloud goes to Key Largo to pay respects to the family of one of the soldiers under his command who was killed in action. McCloud seems a bit aimless having left the army; this obligation he feels to visit the family is about the only purpose he has at this stage in his life.

Having left the Army, ex-Major Frank McCloud goes to Key Largo to pay respects to the family of one of the soldiers under his command who was killed in action. McCloud seems a bit aimless having left the army; this obligation he feels to visit the family is about the only purpose he has at this stage in his life.

The family owns a hotel in Key Largo and when McCloud gets there both he (and we, the audience) sense something is up. Some shady characters are hanging around the hotel and they seem eager for McCloud to leave.

As the movie unfolds, it turns out they are criminals. They take over the hotel as they await other criminals to meet up with them in order to conclude a deal concerning counterfeit money. It also turns out they are led by Johnny Rocco (Edward G. Robinson) who has returned to reclaim his life and position in the criminal world, from which he has been gone for eight years (likely in prison).

Unfortunately for the gang of thugs, this is Florida and it is hurricane season and one is blowing in.

What the movie does is to bring all these characters together in one place and confine them in close quarters. You feel the walls closing in, so to speak, as the winds get stronger and shutters are closed. They are all closed in; sunlight vanishes.

What the movie does is to bring all these characters together in one place and confine them in close quarters. You feel the walls closing in, so to speak, as the winds get stronger and shutters are closed. They are all closed in; sunlight vanishes.

The movie’s true is star is arguably Edward G. Robinson. He’s mean and menacing and dominates everything around him. Once he appears in the movie (which is not immediate), he seldom leaves the frame.

There is a curious contrast between Robinson’s Johnny Rocco and the other characters. In many ways, they are all frozen in the moment, unsure what to do (except Rocco). Because of the death of Bacall’s husband, who is also Barrymore’s son, those two are stuck. McCloud, discharged from the Army, is unsure what to do with his life. They would all like to go forward; they’re just not sure how.

But Johnny Rocco has no interest in going forward. He wants to go back. He wants to reclaim and relive his former glory. He lives in, and dreams of, the past. Claire Trevor’s character, Gaye Dawn, is also stuck in the past because she is still connected with Rocco and she is an alcoholic. The relationship is abusive but she is dependent on Rocco, or so she feels. She is stuck and, because of her association with Rocco, it is the past she is stuck in.

Just as they are all confined within the hotel, so they are confined within this moment of uncertainty about their lives. They aren’t living in the present; they are confined within it.

Tension builds in the movie partly because of the storm, partly because Johnny Rocco gets increasingly anxious about completing his deal, but also because of the forward and backward pull between the characters: Johnny’s will to go back to the past; McCloud and the others’ desire to break free and go forward into the future.

Tension builds in the movie partly because of the storm, partly because Johnny Rocco gets increasingly anxious about completing his deal, but also because of the forward and backward pull between the characters: Johnny’s will to go back to the past; McCloud and the others’ desire to break free and go forward into the future.

Dramatic and suspenseful, Key Largo is a tremendous example not just of good filmmaking but of good drama, period. It’s a good story well told. I loved it.

On Amazon:

- Key Largo (DVD) — Amazon.com (U.S.)

- Key Largo (DVD) — Amazon.ca (Canada)

The Orson Welles movie Orson Welles didn’t like

I was very pleasantly surprised last night when I watched The Stranger, a movie I hadn’t seen before and knew little about, and found it wonderful. Apparently the director didn’t feel the same way, however, or so I’ve read.

The Stranger (1946)

Orson Welles’, The Stranger is an enthralling noir that has received some pretty shabby treatment over the years, not the least of which is by Welles himself. (Of his movies, it is the one he liked least.)

For most, it seems the movie’s biggest detraction is that it is not Citizen Kane or The Magnificent Ambersons.

For Welles, it seems the movie’s largest problem is that it is his most commercial, the movie he was forced to make to prove he could make a successful movie.

In other words, it tends to be evaluated in a debilitating context. For me, this is a great, if lesser Welles film, one I loved, and perhaps the reason I like it is that is commercial. It is constrained as far as what he could do (as if someone said, “Forget art; make something that sells!”). Maybe it works as well as it does because Welles can’t overly indulge himself.

I don’t know; I can only guess. But I do know it works better than most noirs; better than most movies, period.

Made not long after the end of World War II, The Stranger uses a scenario that is similar to Shadow of a Doubt (1943). It is about evil living – hiding, actually – in the heart of America.

Edward G. Robinson is Wilson, a man hunting down former Nazis and bringing them to justice. Orson Welles is Professor Charles Rankin – the Nazi Franz Kindler, disguised and hiding in small town Connecticut. Loretta Young is Mary, the young woman Rankin is about to marry, someone like everyone else in the town, completely unaware of her fiancé’s past.

Of course, being an Orson Welles movie it isn’t enough that Kindler be a Nazi. He’s portrayed as the Nazi, after Hitler. He wasn’t just part of running a concentration camp; he conceived and designed them.

In order to find Kindler, a man no one can identify visually, Robinson’s Wilson arranges for another Nazi to escape prison – Meinike, a former commandant of a concentration camp – in the hope that he will lead Wilson to Kindler.

I think what most struck me about The Stranger was the degree to which the constraints placed upon Welles appear to help the movie.

It has all the expected Welles’ elements from the off-kilter camera angles, the shadows, and elongated perspectives – even imagery with meaning (such as the clock). Yet it is such a taut movie. It doesn’t flag for a moment.

It may be that the noir style helped Welles as far as achieving coherence. Or perhaps it was the imposition of those constraints and the need to show he could make something that would sell. (Theatrically, The Stranger was Welles’ most successful movie.)

Whatever the reasons, this may be Welles’ best movie from a purely entertainment perspective.

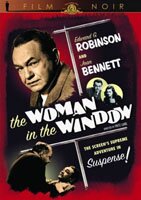

The Woman in the Window – review

Yes, I finally reviewed a movie. And it goes like this:

I’ve had The Woman in the Window (1944) in my “to be watched” pile for a very long time. And this is odd given that I was anxious to watch it. With Fritz Lang directing and the script coming from Nunnally Johnson, I had some fairly high expectations.

I’ve had The Woman in the Window (1944) in my “to be watched” pile for a very long time. And this is odd given that I was anxious to watch it. With Fritz Lang directing and the script coming from Nunnally Johnson, I had some fairly high expectations.

Well, I finally watched it last night and I regret to say it was a disappointment. While it had some good moments and a pretty impressive cast that included Edward G. Robinson, Joan Bennett and Raymond Massey, overall I found it kind of trudged along from scene to scene and, more significantly, suffered from two pretty major story flaws. (Also, for Fritz Lang, who sets a pretty high standard, the directing seemed pretty pedestrian, though it had some moments.)

The first story flaw is Edward G. Robinson’s character who is, depending on the scene, a rather boring, homebody professor, a frightened introvert, a man single-minded, focused and in control, and then a frightened little man. Who in the world was he supposed to be? And who was responsible for this muddled characterization? I find it hard to blame Robinson as I assume this was written into the script. However, shouldn’t the director and actor have voiced some misgivings?

The second flaw for me was the ending. I won’t give it away, though I’m not sure it would matter, but I found it hugely disappointing because it is such a cheap, easy-out trick. It reduces the film to a rather poor installment of, say, The Twilight Zone or Night Gallery, the kind of show that relies on some twist at the end.

I suspect the ending had something to do with the studios. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to find that Lang’s movie ended about two or three minutes before this final version ends, the ending here being something the studio likely insisted on, finding the other too bleak. That’s just a guess but I find it hard to believe Fritz Lang would have wanted this ending.

I suspect the ending had something to do with the studios. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to find that Lang’s movie ended about two or three minutes before this final version ends, the ending here being something the studio likely insisted on, finding the other too bleak. That’s just a guess but I find it hard to believe Fritz Lang would have wanted this ending.

I suppose ultimately the blame falls on Nunnally Johnson for the script. While no one excels in the movie (director, actors etc.), everyone more or less does a competent job. The elements that hurt the movie, and perhaps deflated everyone so they simply did their job and no more, are all in the script.

1 ½ stars out of 4.