No snide comment is implied by “Errol Flynn … gains some gravity,” though by the time this movie was made the older Flynn had put on a few pounds. Rather, his performance has a bit of weight that wasn’t there in the younger Flynn’s roles. You can see it in this movie, The Master of Ballantrae, though I don’t think anyone would rate the movie itself terribly high.

20 Movies: The Saragossa Manuscript (1965)

I love stories like this. By “this” I mean stories within stories within stories. It’s really quite an accomplishment to achieve something like this on film. But The Saragossa Manuscript manages it.

I don’t recall when I first heard of this movie but it would have been about ten years ago, more or less. When I did, I tracked down a DVD copy. Believe me, I was glad I did.

In a number of ways, this is the perfect movie to wrap up my list of 20 movies.

The Saragossa Manuscript (1965)

directed by Wojciech Has

I won’t even attempt to summarize the plot of The Saragossa Manuscript (Rekpois Znaleziony w Saragossie). (See IMDB for a brief summary.) Rather, I’ll simply say I loved this movie and here’s why: narrative style.

The Saragossa Manuscript, set during the Napoleonic Wars, is told in the manner of and, to a lesser extent, The Canterbury Tales.

It is a story about stories that themselves contain stories (which also contain stories). In some ways, it’s a celebration of storytelling. In the world of written literature, this kind of narrative has a long history. Cinema, however, is a bit different.

Movies are less like novels than they are like short stories and novellas. In other words, a movie story needs to be told all at once (rather than over several days like a TV series or a book you set aside between chapters). Audiences simply can’t (and won’t) sit through 6 or 7 hours (or longer) of film. Nor would budgets allow for the creation of such a monster (Lord of the Rings aside). So films are more compressed (at least when they try to replicate a novel cinematically). Or, with an original script, less wide-ranging and more tightly focused.

Director Wojciech Has achieves a remarkable accomplishment, then, by giving us an engaging film that is wide-ranging and broad. Based on the novel of the same name, and definitely abridged (for the reasons mentioned above), his movie layers story upon story, each somehow touching upon the others, sometimes echoing them, sometimes growing out of and into them.

The result is a delight and, at a running time of 3 hours, one that never flags and loses our attention. Sometimes dark, sometimes bawdy, sometimes funny and sometimes dramatic, in a single film we’re taken into the strange and wonderful world of storytelling.

If there is a theme to it all (beyond the joy of telling stories), it may be the liberating power of fantasy and imagination.

The main character, very focused, disciplined and rigid (on the surface at least), and in denial of anything that doesn’t conform to empirical reality, goes on a journey that transforms him if only by opening him up to possibilities.

Admired by such names as Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese and (oddly) Jerry Garcia, The Saragossa Manuscript DVD is a clean, crisp version (taken in the context of its age and the fact it had to be restored).

Filled with stunning images and moving from the strange to the lascivious to the dramatic, this is a fabulous film and a definite must for anyone who loves stories and wishes to see how film is simply another branch of literature (albiet one with its own rules and traditions).

(Originally posted in 2003.)

See: 20 Movies – The List

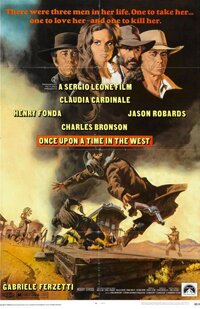

20 Movies: Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Look out. I’m back to westerns. I love them.

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

directed by Sergio Leone

From it’s incredible opening to the closing credits, Once Upon a Time in the West is a mesmerizing movie about westerns. In a way, it isn’t even about westerns. It simply evokes them with a stream of iconic images.

The movie takes a simple, almost cookie cutter story, and uses it as a basis (and excuse) for a film that is essentially concerned with western myths and iconography. (Sergio Leone had done this before, as in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.)

It’s a post-modern film; it takes a kind of deconstructionist approach to movie-making (which may seem a tiresome idea today but was unusual in 1969).

At the centre of the film’s narrative is Claudia Cardinale as Jill. Around her three other characters revolve: Henry Fonda as Frank, Jason Robards as Cheyenne and Charles Bronson as the man with no name (often referred to as Harmonica).

The owner of a railroad company, Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), hires a psychotic gunfighter, Frank (Henry Fonda) to get rid of anyone in the way of the completion of his railroad.

The owner of a railroad company, Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), hires a psychotic gunfighter, Frank (Henry Fonda) to get rid of anyone in the way of the completion of his railroad.

Frank does, by massacring the family of new bride, ex-whore, Jill.

With her new family dead, Jill must decide what to do with the land she has inherited. It seems worthless but proves to be very valuable, so valuable it is the reason her family has been killed. It’s a basic western formula: bad guys after the good guy’s land. He must defend it and himself, except in this case “he” is “she.”

At the same time, bad-guy Frank starts being stalked by a mysterious stranger (Charles Bronson). Frank doesn’t recognize him, he has no idea what the stranger wants. As for Jason Robards’ Cheyenne, he gets involved in all of this because Frank has framed him for the killing of Jill’s family.

At the same time, bad-guy Frank starts being stalked by a mysterious stranger (Charles Bronson). Frank doesn’t recognize him, he has no idea what the stranger wants. As for Jason Robards’ Cheyenne, he gets involved in all of this because Frank has framed him for the killing of Jill’s family.

For a film almost three hours long, it doesn’t seem much to work with. But Leone is interested in the storyline only to the extent that it provides him something to improvise on western themes and imagery. He plays with these and it is what he does with them that makes this such a great movie.

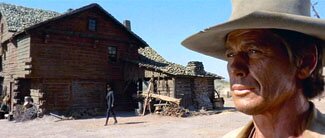

I can’t imagine how this would look in pan-and-scan form. Leone makes incredible use of the screen’s width, visually stretching it out with foregrounds oriented to one side and breathtaking backgrounds to the other.

He also contrasts the breadth and spaciousness of his wide shots with the most extreme of close-ups. He shoots human faces almost as if they, too, were landscapes. The opening sequence is a spectacular example of this as he lingers on the bored killers’ faces. He shows us every detail from lines to whiskers. You almost get the sense he uses only two shots – very close or very long.

He also contrasts the breadth and spaciousness of his wide shots with the most extreme of close-ups. He shoots human faces almost as if they, too, were landscapes. The opening sequence is a spectacular example of this as he lingers on the bored killers’ faces. He shows us every detail from lines to whiskers. You almost get the sense he uses only two shots – very close or very long.

He also uses his trademark technique of drawing scenes out to their absolute limit. The opening goes something like eight minutes before anyone says anything and it is a scene simply about three guys waiting at a train station. You get an almost visceral sense of their tedium.

With scenes like gunfights, they are choregraphed to evoke iconic imagery and are paced, again, incredibly slowly to draw them out to their limits. When violence does erupt, it is explosive and very brief. Leone has little interest in violence itself but is obsessed with its rituals.

Whether the movie is about anything is debateable. Leone seems interested primarily in style and evoking the western. (Once Upon a Time in the West is littered with references to earlier Hollywood westerns like High Noon, The Searchers and numerous John Ford films. It’s even partly shot in Monument Valley where Ford shot so many of his westerns.)

Whether the movie is about anything is debateable. Leone seems interested primarily in style and evoking the western. (Once Upon a Time in the West is littered with references to earlier Hollywood westerns like High Noon, The Searchers and numerous John Ford films. It’s even partly shot in Monument Valley where Ford shot so many of his westerns.)

If there is a comment in the film, perhaps it is a critique of myths of America. In the film, everyone is dissatisfied. Everyone wants something more, from the railroad baron and his hired killer Frank, to the woman Jill and Jason Robards. In the land of the free, no one seems to be content with their lot (except, perhaps, for the murdered McBain.)

There may be something to the use of the railroad, too. Its arrival signals the end of the mythological West and the beginning of the modern age in the last American frontier. The train represents encroaching European civilization and the end of the mythical West, just as the film Once Upon a Time in America is a eulogistic end of the western.

There may be something to the use of the railroad, too. Its arrival signals the end of the mythological West and the beginning of the modern age in the last American frontier. The train represents encroaching European civilization and the end of the mythical West, just as the film Once Upon a Time in America is a eulogistic end of the western.

But in the end, the film is simply a great homage to westerns, as well as a kind of eulogy to them. It’s a stream of riveting images; an almost symphonic evocation of filmmaking style.