I actually wrote the ‘review’ below about ten years ago. But I watched The Shop Around the Corner a few days ago and wanted to make a few changes, though I also forced myself to leave in some of the howlers, like the “wow” business.

It still doesn’t say what I’d like to say about Lubitsch (not that it’s anything life changing). But my last post and this one are part of me getting to what it is I’d like to write. Have I mentioned how much I love his movies?

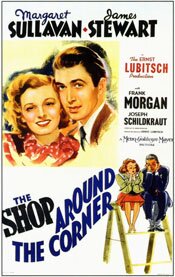

The Shop Around the Corner (1940)

The Shop Around the Corner (1940)

Directed by Ernst Lubitsch

Wow. What a great movie! I suppose that’s why so many remakes have followed it, including You’ve Got Mail. But while the attempts may have been well-meaning, there’s nothing like the original, The Shop Around the Corner.

One of the interesting things I find about this film is the fact that the setting, even the story, are so unlikely, so lacking in credibility, yet the film is unquestioningly true. How does that happen? The movie could care less about whether or not it is realistic. It’s pure romantic fantasy. (Think about it: Jimmy Stewart as a sales clerk in a gift-shop in Budapest?)

Yet reality informs the story and its characters. But it’s not the objective reality of science and journalism; it’s the reality of behavior and relationships. It’s the reality of people.

The conceit of the film is pretty simple, which may be why it is such a template for other movies: Alfred (Jimmy Stewart) and Klara (Margaret Sullavan) have begun corresponding by letter as the result of Alfred stumbling across a classified ad Klara has put in the paper for a pen-pal. Both become enamoured of the person they think they are corresponding with.

The conceit of the film is pretty simple, which may be why it is such a template for other movies: Alfred (Jimmy Stewart) and Klara (Margaret Sullavan) have begun corresponding by letter as the result of Alfred stumbling across a classified ad Klara has put in the paper for a pen-pal. Both become enamoured of the person they think they are corresponding with.

A romance develops between them though they have never met. Within the fantasy that is the movie, we have two characters living fantasy lives.

In the meantime, Klara has become a clerk in the same shop where Alfred is the longest serving employee. The two find they can’t stand one another; they continually bicker.

There are various complications along the way, but you can guess where the film is going. Eventually the truth must come out, and it does.

The film works well for a number of reasons. One of these is the directing of Ernst Lubitsch. Everything flows, and there is total acceptance of the fantasy world. The performances he gets from his cast are also flawless. They’re wonderfully nuanced performances.

Jimmy Stewart portrays Alfred so naturally it’s hard to imagine it’s acting. (It’s very similar to the easiness of the performance he gives in a film like Harvey.)

Margaret Sullavan is a terrific companion for him and the supporting cast, especially Frank Morgan (the Oz from The Wizard of Oz), are also brilliant.

Margaret Sullavan is a terrific companion for him and the supporting cast, especially Frank Morgan (the Oz from The Wizard of Oz), are also brilliant.

The Shop Around the Corner is an almost perfect romantic comedy. It does everything a romantic comedy should do. It feels real while being so obviously fantastic. It’s one of the most delightful and charming films ever made.

I also highly recommend reading Self-Styled Siren’s piece on Jimmy Stewart and The Shop Around the Corner. It’s called .

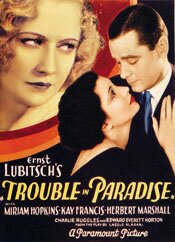

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

Trouble in Paradise (1932) Much is made of the “

Much is made of the “ But this is what Hitchcock would call the

But this is what Hitchcock would call the  As Peter Bogdanovich mentions in his introduction to the Criterion DVD of the film, it’s a wonder this was ever made in Hollywood, particularly when we see where we are today.

As Peter Bogdanovich mentions in his introduction to the Criterion DVD of the film, it’s a wonder this was ever made in Hollywood, particularly when we see where we are today.