I recently finished reading Stefan Kanfer’s Tough Without a Gun: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of Humphrey Bogart. (The title is from something Raymond Chandler said of Bogart.) So of course, I’m back to watching Bogart movies, at least for the time being.

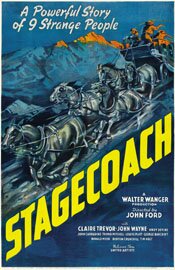

An imposing little Stagecoach from John Ford

When you think of how long it takes to make a movie today, at least a Hollywood movie, it’s quite astonishing to find John Ford cranked out three pretty extraordinary movies in 1939. His “go to” guys in that period were Henry Fonda and John Wayne. (In 1939-1940, he made five films — three with Fonda, two with Wayne.)

The number of movies isn’t the amazing part, though it is notable; what is remarkable is the quality of those films. (The movies are Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home.) For many, that creative glut would be a career. With Ford, some of his best films were still ahead of him.

Stagecoach (1939)

Stagecoach (1939)

Directed by John Ford

For what is essentially a simple western, Stagecoach is a pretty imposing little film. It’s daunting for all the film history associated with it, beginning with the introduction of John Wayne as movie star. (His first starring role was in Raoul Walsh’s 1930 movie The Big Trail. But it was John Ford and Stagecoach that made him a star.)

Interestingly, Wayne wasn’t the big star of Stagecoach. Claire Trevor was. She gets top billing and the movie is an ensemble piece, so no one character really dominates as they do in a “star vehicle.”

The movie also gave us Monument Valley, in Utah, which would afterward be forever associated with John Ford and be the quintessential “old West” landscape with its plateaus, mesas and buttes. And for many, this is the movie where Ford’s cinematic eye for people and landscapes — often low-angled shots; often sky dominated — is first seen.

There is one shot in particular that I loved. The upper two thirds of the frame is cloud fluffed sky. The lower third is plateau with a mesa off to the right; nothing but dessert otherwise, but for a trail with the lonely stagecoach winding along it from right to left, small and vulnerable.

The story is simple enough and one that is standard fare now: a group of people on their way from here to there, in this case on a stagecoach, encountering and overcoming various threats along the way.

In this movie, the threat comes from Geronimo as the stagecoach is passing through hostile Apache territory.

Riding the stage with the marshal (George Bancroft) are the “proper” lady, Lucy (Louise Platt) and the banker (Berton Churchill) … and a number of social outsiders. The hooker, the drunk, the outlaw … all with stronger moral codes than those who make up the proper society from which they’re excluded.

Both Dallas (the hooker) and the constantly inebriated Doc Boone (Thomas Mitchell) have been run out of town by self-appointed guardians of social mores.

Along the way, they meet up with the Ringo Kid (John Wayne), the outlaw. Though a disparate group and one at odds with itself, it is in working together that they make it to their destination.

As far as the story goes, the movie is nothing exceptional, at least not today. It’s significance is in what it means historically, as far as cinema goes, and John Ford’s directorial work.

Even though many of the things Ford did have since been copied and have become fairly common, the look of Stagecoach is still striking; more so when seen in its historical context.

For any serious lover of westerns, this movie is a must.

Apart from being at the start of an extraordinary string of westerns from John Ford that cover decades, it also gives us that moment when the camera moves in on John Wayne’s face announcing, in no uncertain terms, “Meet your favourite star for the next forty years.”

Yes, John Wayne was around for a long time after this movie came out. It should also be mentioned that simply as a movie, this is one very good film.

(In this same year, 1939, Ford would also direct Young Mr. Lincoln and Drums Along the Mohawk.)