Last week I went on a run of watching and writing about some Myrna Loy and William Powell movies I have in my collection. I went through four five of them, three four of which I’ve had here, unwatched, for about five years.

Garbo’s Mata Hari just looks peculiar

It seems like it should be a great story. First World War. Female spy using sex to steal secrets. Executed in the end. Amidst all that? The devious user of love for espionage falls in love herself (as the movies would have it). The result, however, is not so much great as peculiar.

The great and debatable Red River

I really go on a ramble here about this movie, though it is more a ramble about John Wayne’s acting and speech pattern than the film. This is considered one of the great westerns by many and I would be among them. However, while I like Wayne in it and think it’s one of his best roles, it is not my favourite John Wayne performance.

When style beats the pants off of story

Among the many fascinating and, in this case, amazing things about The Maltese Falcon is that it was the first film for Sydney Greenstreet who was 62 years old at the time. Can you imagine any actor today getting a role, much less starting a career at 62?

High Sierra: When the bad guy is the good guy

I recently finished reading Stefan Kanfer’s Tough Without a Gun: The Life and Extraordinary Afterlife of Humphrey Bogart. (The title is from something Raymond Chandler said of Bogart.) So of course, I’m back to watching Bogart movies, at least for the time being.

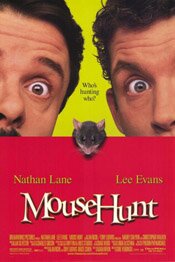

Loving and hating Mouse Hunt

Mousehunt (1997) is a funny movie in both senses of the word. It is funny “ha ha,” and it is funny peculiar.

Mousehunt (1997) is a funny movie in both senses of the word. It is funny “ha ha,” and it is funny peculiar.

For me, it is one of the funniest movies I’ve seen. Ever. I can’t think of many movies, if any, that have made me laugh out loud like this one does.

Other people, however, either like it as I do or absolutely hate it. There is no middle ground. I don’t think I’ve met anyone that felt it was “okay” or “not that good.”

They love it. Or, they hate it.

I suspect it is because the humour is so broad and slapstick. Though there is also some very funny dialogue, it is very visual humour. To an extent, it could be compared to the Three Stooges — at least as far as the visual jokes go.

Oddly, though I love Mousehunt I’ve never been a big fan of the Stooges.

Nathan Lane and Lee Evans are two brothers, Ernie and Lars Smuntz. They inherit a dilapidated house when their father dies along with a string factory that desperately needs modernization. The brothers don’t always agree. One reason is that Lars is simple and kind, for the most part, whereas Ernie is cynical and self-centred.

It’s decided (thanks to Ernie) that they will fix the house up, at least superficially, and then sell it quickly to get whatever they can for it. Then they find out it has historical significance — it’s “the missing Larue,” designed by a famous architect — and worth boatloads of money. They’re thrilled, however …

There is a mouse living in the house and it has other ideas.

As Ernie says later in the movie, after numerous painful attempts to get rid of the mouse, “He’s Hitler with a tail. He’s “The Omen” with whiskers. Even Nostradamus didn’t see him coming!”

The movie builds from one attempt to another, each more elaborate, each with a more disastrous result. There is one sequence when the brothers bring in ‘Caeser, the Exterminator’ (Christopher Walken) to rid the house of the mouse that is hilarious. Walken gives wonderfully oddball performance as Caesar.

But it’s Lee Evans as Lars that really stands out for me. Tall and gangly, he contorts his body amazingly as he delivers the slapstick humour in a brilliantly visual fashion. Onscreen, he and Nathan Lane make for a tremendous comedy team.

The movie also has a Tim Burton-like look to it; there is a distorted (as in alternately distended and extended), cartoon-ish feel to some of the sets, some camera angles and certain action sequences. The humour is not Tim Burton-like, however. It’s much more direct. It makes no effort at subtlety. That may be why it works so well.

Mousehunt was the first full length movie directed by Gore Verbinski, best known now for his Pirates of the Caribbean movies. He has also directed The Mexican (2001) and The Weather Man (2005). Though quite different movies (especially Weather Man) it strikes me that humour is a key element running through his films and of those he experiments with in the sense that Mousehunt is slapstick, Weather Man satire of a dark variety, and Pirates somewhere between.

Whatever the case, I think it’s safe to say you’ll either love or hate Mousehunt. You have to watch it first, however, to find out which.

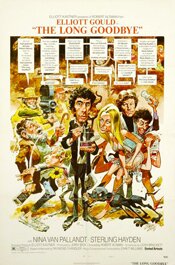

A curious Long Goodbye from Robert Altman

To be honest, I’ve never been a big Robert Altman fan, though increasingly I’m finding his movies more appealing. I think his approach creates the sense in me that I’m listening to a slow-talker and I want to interrupt and say, “Move it along; get to the point.” There’s an improvisational feel to character interaction and part of me want’s it more closely scripted and edited.

In The Long Goodbye this comes across partly because Altman gives his actors more responsibility to actually act, as he does with Elliott Gould here, and partly because the camera is constantly moving, as if you as a viewer are watching and trying to find a better vantage point. Some shots are through windows; some are even reflections in windows.

It’s intriguing, yet for me a bit irksome — but that’s just a personal, subjective thing. And what is odd about it is that I like this movie nonetheless.

The Long Goodbye (1973)

The Long Goodbye (1973)

Directed by Robert Altman

Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye is a bit like a fast food hamburger. It has beef in it but also has so many other things, and it has been altered to such a degree, that while it resembles a hamburger, it ain’t no hamburger.

In the same way, Altman’s movie is Raymond Chandler’s book, and resembles a film version of that book, but it ain’t Chandler’s book.

But then, you wouldn’t expect Altman to make a movie utterly faithful to its source.

Altman’s movie begins with the question, “What would happen if Marlowe, a character of the 40s and 50s, were to wake up and find himself in the early 70s?” In an interview, he says they referred to it as “Rip Van Marlowe” during the making of the movie. This idea dictates how the movie plays out.

Chandler’s Marlowe began in 1939 with The Big Sleep. His book The Long Goodbye was published in 1953. That is exactly twenty years before Altman’s The Long Goodbye.

Chandler’s Marlowe had been in about six books prior to the 1953 book. In The Long Goodbye, his Marlowe is older and mellower. The novel is a bit more reflective and, in my opinion, weighty. There is less emphasis on the tough guy posturing of the early books; he comes across as a more mature character. In some ways, there is a sense of alternating melancholy and apathy in him.

This may be what suggests the “Rip Van Marlowe” possibility to screenwriter Leigh Brackett and director Altman, or at least what makes this book a possible vehicle for working out that theme. However, there is more to the theme than just the “what if” aspect of a man from 1953 waking up in 1973. One thing that has changed for Marlowe is how people view friendship. The world has a different sense of ethics and morality and it isn’t in sync with his.

The movie opens with Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) literally waking up. The first half of the movie, particularly the first twenty minutes or so, give us such a slovenly, disconnected and half-asleep Marlowe that, the portrayal being so effective, he is incredibly annoying. He speaks under his breath, muttering to himself more than anyone else, even when responding to others around him. He’s almost completely unengaged with his world.

He shows no animation at all until his friend, Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) shows up at his door. This is where the story’s engine turns over and it gets underway as Terry asks Marlowe to take him to Mexico.

The story makes some major turns from the Chandler book, some for the purposes of condensation and some … Perhaps because they didn’t want to make a movie faithful to its source but one that stood on its own legs as unique.

Having re-read the book recently (which is probably why I keep referring back to it), and it being my favourite of the Chandler novels, I can’t say I like the deviations. I found the book had more meaning for me than the movie largely because of those things that have been changed, though I do like the movie on its own merits.

But the book’s ending is much more effective and moving, I think. The movie is very direct – you can’t miss its point. In a way, it’s like Altman believes he has to be direct because people in 1973 are as much asleep as Marlowe was. His conclusion is like a bucket of cold water in the face.

The “asleep” idea recurs through the movie. It’s not just Marlowe who is somnambulant. His neighbours, the young women with their yoga and exercise, appear to be lost in their own world of new age exercise and spirituality. Roger Wade (Sterling Haydon) is lost in his alcohol and self-pity. Everyone is self-absorbed and inward looking and Marlowe is the one person who “wakened” to this contagion of social sleepwalking.

Marlowe “wakes up” because something has wakened him: the death of his friend Terry Lennox. He remains true to his friend, though for all intents and purposes it’s meaningless, isn’t it? (Terry is dead, after all.) Yet Marlowe won’t believe the murder and suicide that are being attributed to his friend.

No one else in the movie is true to anyone or anything. Even Marlowe’s cat abandons him when its favourite food is no longer there. Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell) speaks of how much he loves his girlfriend then strike her horribly for no reason. Roger Wade hits his wife when he is drunk.

Throughout the movie, as Marlowe makes his way, he sees a world of self-interest and no loyalty, making him an anachronism. When asked why he would try to clear the name of Terry Lennox, he hears variations of, “What’s it matter? He’s dead.”

The ending aside, this is probably the greatest deviation from the novel. In the book, respect and loyalty keep appearing – Marlowe is hired for his; the gangsters in the book (unlike the Marty Augustine character) respect Marlowe for his loyalty. Even some of the cops do. He is sought out and hired because it’s reported in the newspapers that he was picked up by the police for questioning and wouldn’t talk.

So the difference in the endings becomes a bit curious. Is it simply a more overt, can’t-miss-that meaning concerning betrayal of a friendship or is it also suggesting that Marlowe, too, is becoming part of that amoral culture of self-centeredness?

I’m not really sure. But I do know this is a curious movie Robert Altman has given us.

Chess games and submarine movies

You might think that movies set on submarines are relatively rare. They are — relatively. But as a quick search online will show you (as it just showed me), there are actually quite a few of them. (Das Boot and Crimson Tide come to mind.) Relative to other movies, they may be rare. But there are quite a few of them nonetheless.

This leads me to the two movies I wanted to bring up: Run Silent, Run Deep (1958) and The Hunt for Red October (1990). I don’t know what the correct term for describing them would be — suspense, thriller, action? I lean toward suspense but what makes them compelling is a phrase Sean Connery’s character, Marko Ramius, uses in Red October: chess game.

This leads me to the two movies I wanted to bring up: Run Silent, Run Deep (1958) and The Hunt for Red October (1990). I don’t know what the correct term for describing them would be — suspense, thriller, action? I lean toward suspense but what makes them compelling is a phrase Sean Connery’s character, Marko Ramius, uses in Red October: chess game.

There is more actual “action,” as in torpedoes and so on, in Run Silent, Run Deep, but neither film has a great deal of it. It’s the drama of the situations and, again in both films, the mystery surrounding a lead character’s motives, Clark Gable’s in Run Silent and Sean Connery’s in Red October.

Both movies get more physically and visually dramatic with action in their final acts but for the most part these chess games are mysteries rather suspense thrillers, though both are suspenseful and, I suppose, thrilling.

However they are described, I like both movies quite a lot and have watched both many times. They are well worth seeing more than once ….

Run Silent, Run Deep (1958)

I saw an interview with the actor Laurence Fishburne the other day in which he was speaking of various influences when he was young. At one point, he brought up the movie Run Silent, Run Deep and Clark Gable. What struck him in the movie was Gable’s gravitas. I immediately thought, “Yes, that is the perfect word for it.” (Read more)

The Hunt for Red October (1990)

In the class of movies known as action-adventure, The Hunt for Red October stands out as one of the best and as one of the strangest because the action is relatively minimal and doesn’t play a huge role in generating the film’s suspense and tension. (Read more)

The accidental film noir: I Wake Up Screaming

It’s Day 2 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to (or use the button on the right). Today I have a quickly scribbled, un-proofed, un-thought through look at the movie I watched last night. The studio considered calling it Hot Spot but, according to the DVD I have, the actors insisted on them using the original name, which is …

I Wake Up Screaming (1941)

Directed by H. Bruce Humberstone

As I watched I Wake Up Screaming last night I had two thoughts running concurrently. First, this should not be a good movie. Second, somehow it manages to be a good movie. How does that happen?

I’m not sure. I think it lies partly in Betty Grable, whose performance is a level above the other main actors in the movie.

It’s also in the characterization of Ed Cornell, played by Laird Cregar, who seems a cross between Vincent Price (in the slightly effeminate voice and its cadence) and possibly a low rent version of George Sand. (I mean vocally, nothing else, and not much there either. But there seems to be something vaguely Sand-ish in the voice.)

Cregar’s Cornell is creepy, to say the least, and that makes the movie compelling. Though the film’s mystery may be obvious, it doesn’t matter. The creepiness keeps us fascinated in a “slowing down to view the accident” kind of way. Cregar’s character isn’t the only one that gives us the willies.

Elisha Cook Jr.’s Harry is equally troubling. Soft-spoken and gentle, his focus and attentiveness to Grable’s Jill Lynn leaves us feeling something isn’t right about him. He’s stalker material.

Much of what makes the movie watchable is in the script. The bad guys in this movie – and there are a lot of them – are not villains so much in the commitment of crimes regard, as in their psychology. In fact, most of them have stalker-like personalities or variants of it.

They are all focused in some way on Vicky Lynn, played by Carole Landis. They want to either possess her, use her, or both. And she, being ambitious, is happy to permit it as she uses them. Thus, in a sense, she invites what follows from it.

Into this morass of twisted personalities come Victor Mature as Frankie, a kind of nice if goofy sports promoter (who find himself accused of murder) and Vicky’s sister, Grable’s Jill Lynn.

Frankie and Jill are the normal ones (for lack of a better word) and also the ones who suffer the consequences of a world populated by twisted personalities.

Visually, the movie delivers the noir goods but that may be less an aesthetic decision as a kneejerk response to making a crime movie in the forties. Crime equals scenes of darkness and shadow, ergo scenes of darkness and shadow. I get the sense director H. Bruce Humberstone was a paint-by-numbers kind of director, though that may be unfair to him. But that is how it strikes me.

Still, by accident or design, the movie looks good as a noir. It has a low budget feel and some very nice shots, especially near the end where we see Mature looking down at Harry snoozing at the front desk.

Overall, then, I Wake Up Screaming strikes me as an accidental noir. It discovers a noir world in the script it brings to the screen and in the kind of kneejerk response of how it visually portrays that script.

Much of what happens on screen is highly melodramatic and it would be too much were it not for the material driving it, Laird’s unsettling Cornell, and Grable’s much better anchored performance as Jill. Victor Mature looks great as a noir character, especially in the interrogation scenes, but he is often well over-the-top. Also, for about two thirds of the movie, once outside the interrogation room (and often within it) he plays a goofy kind of guy without a care in the world. It’s deliberate, in part, as it’s an aspect of the character. But it just seems too much.

And having gone on with all these negative comments about the movie, I still have to say I liked it quite a bit. However, it feels to me it’s a good movie through dumb luck; a film noir by accident.