Such a study in contrasts! On TCM the other night there were a few William Holden movies running. I tuned in as they were running the marvelous Sunset Boulevard, one of my favourite movies. It was followed by the movie below and … oh my!

The great and debatable Red River

I really go on a ramble here about this movie, though it is more a ramble about John Wayne’s acting and speech pattern than the film. This is considered one of the great westerns by many and I would be among them. However, while I like Wayne in it and think it’s one of his best roles, it is not my favourite John Wayne performance.

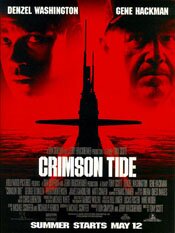

Characters in close quarters – Crimson Tide

You wouldn’t immediately associate submarine movies with a film like Key Largo but they have something in common. The dramatic tension comes about by having characters constrained within close quarters. In Key Largo, it’s within a hotel because of a hurricane; in submarine movies it’s due to the nature of submarines.

I don’t like a phrase like “submarine movies” but there is no getting around the fact there is a kind of sub-category of action-adventure films characterized by where they are set — on submarines. They’re often among the best of the action-adventure variety of films because of the close quarters that seem to force filmmakers to concentrate on characters.

Crimson Tide (1995)

Crimson Tide (1995)

Directed by Tony Scott

In the tradition of movies like Run Silent, Run Deep, The Hunt for Red October and Das Boot, the Tony Scott directed Crimson Tide is submarine drama with strong lead characters. If it distinguishes itself from those previous movies it is by being faster moving and much noisier.

That may not sound overly appealing but it be would wrong to think that way. This is a very good, very engaging action-adventure with a strong foundation: the performances of Denzel Washington and Gene Hackman.

It’s also supported by strong performances by its supporting cast – Matt Craven, George Dzundza, Viggo Mortensen and James Gandolfini, to name a few.

Without its strong cast, I think this would likely be just an average film but with them it is firmly anchored.

There is a state civil war in Russia. Rebel generals have taken over a base with nuclear weapons and it appears as if they may use them. The U.S. naval sub Alabama, nuclear-armed, is sent to Asian waters to await instructions. They get them: prepare your missiles. A further message, only partially received, may be orders to fire them or to stand down. It is unclear.

The movie’s conflict is between the sub’s captain (Gene Hackman) and its new executive officer (Denzel Washington). For the missiles to be fired, the two must be in agreement. They aren’t. The captain wants to fire; his second in command does not.

What makes movies like this dramatic and appealing (and you see this in films like Run Silent and Red October) is that the “bad guy” is external – off set. The leads, in this case Hackman and Washington, are both good guys but they are at opposing ends about what to do and thus in conflict.

This increases the film’s conflict by removing the easy, black and white choice and while an audiences’ sympathy may align with one, they can’t easily dismiss the other.

This is also reflected in the unfolding of the film’s drama where the sub’s crew must choose sides, many of whom are conflicted (like Mortensen’s Lt. Ince). We end up with struggles in the submarine, including mutiny, because of the lack of clarity. It’s all due to the ambiguity of the last orders received.

The movie doesn’t ease its audience into the story; it throws them in head first. Music and editing thrum as it begins with a journalist describing events in Russia. There is no slow unfolding of exposition. Director Scott and producer Jerry Bruckheimer take the approach of throwing the audience in at full speed. Details fly by like rapid fire flash cards.

In some movies, this is noise and fury approach can be a gimmick to mask an uninspired story but in Crimson Tide it’s a quick and effective way to get quickly to what is an intelligent, well told story. Perhaps its due to the close quarters of submarines, but movies like this seem to lend themselves to dramatic, character-driven films.

While my own preference is for the quieter tension of a movie like The Hunt for Red October (which I find more effective), it works for Crimson Tide as it delivers a compelling film that leaves an audience with something to question and discuss when is over.

On the whole, this is a very good movie and well worth seeing and more than once.

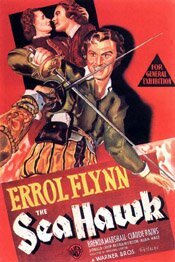

The impish Errol Flynn in a swashbuckler

A few years ago I bought a fistful of Errol Flynn movies that were in one of those many Warner Brothers collections. I had only vague memories of Flynn movies but was curious having seen The Adventures of Robin Hood and, a few years earlier, having read his autobiography, My Wicked, Wicked Ways (recommended, by the way — it is so much fun to read).

Among the movies in the collection was the one I scribbled about below, The Sea Hawk. Interestingly, just as Robin Hood was directed (in part) by Michael Curtiz, he also directs this movie. He seems to have been aware of what Flynn brought to these movies and was very good at getting it.

The Sea Hawk (1940)

The Sea Hawk (1940)

Directed by Michael Curtiz

I’m halfway through Errol Flynn: The Signature Collection and I think I’ve hit the real gem of the lot. (Not that the others aren’t good too.) It’s The Sea Hawk and it really does put the “swash” in swashbuckler.

It’s absolutely brilliant and in a number of respects. I can’t help comparing it to The Adventures of Robin Hood. It has much of the same feel while at the same time has a little something different.

For one thing, both films capture a sense of fun and exuberance. Both also manage to be rousing costume adventures without any sense of self-consciousness though The Sea Hawk differs slightly in that Errol Flynn plays the British pirate Captain Geoffrey Thorpe with a kind of very contained impishness.

His captain is apparently quite serious, patriotic and heroic, yet every now and then he seems to be restraining a smile or grin.

As someone in the special feature on the DVD says (The Sea Hawk: Flynn in Action), it’s almost as if Flynn is asking the audience, “Are you really buying this?”

But in these Flynn movies this kind of feeling is not one of mocking the audience but of having fun with them. Flynn seems to play his swashbuckling roles the way the early Springsteen played concerts – the more fun the audience had, the more fun he had and together they create a kind of synergistic relationship.

Another fascinating way in which The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Sea Hawk compare is in their look. Where Robin Hood is an incredibly exuberant display of colour, The Sea Hawk is nothing less than a magnificent example of black and white. (Although I could have done without the Panama scenes done in sepia.)

The sea battles between the ships are fabulous.

We know from recent films like Master and Commander that great sea battles can be done in colour but I’ll take The Sea Hawk’s scenes anytime. (It’s also incredible to think these were done on sets.)

There is also a great sword fight (as there must be to conclude an Errol Flynn swashbuckler) where, again, the black and white scenes with their use of light and shadow are exceptional. I loved the great shadows on the walls during the struggle.

The Sea Hawk is about as close to the quintessential swashbuckler as you can get. It has Errol Flynn, the man who pretty much defines the hero of such movies.

It has the great set pieces like the sea battles and the swordfights. And it has the music that has influenced the sound of almost all heroic adventures.

Credit for the music goes to Erich Wolfgang Korngold. His score (which is apparently not just rousing but quite clever as it uses, in part, themes from the earlier The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex but in a reworked form), is operatic which, if you think about it, is really what such romantic adventures require.

I really didn’t know a great deal about The Sea Hawk before watching it. And to be honest, I wasn’t expecting a great deal. I basically put it in the DVD player because I wanted to watch something and I hadn’t seen this one yet.

As often happens, when I was least expecting it, I encountered a wonderful movie. Highly recommended.

(The Sea Hawk also aired last night on TCM. I missed it but I may watch my copy again tonight. The above was written roughly about April 2005.)

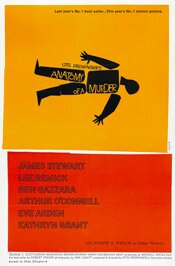

Who dunnit? What did they do? Who cares? – Anatomy of a Murder

It’s Day 4 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. And if you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down this page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

What I like about Anatomy of a Murder is that every so often a friend will say something like, “… This movie I saw on TV was so good …” As they describe it I realize what movie they mean and remark, “That’s Anatomy of a Murder.”

What I like about Anatomy of a Murder is that every so often a friend will say something like, “… This movie I saw on TV was so good …” As they describe it I realize what movie they mean and remark, “That’s Anatomy of a Murder.”

“Yeah! That’s what it was called!”

I mention this because many of these people usually have to make what I called cognitive adjustments in a post not long ago. They don’t like “old movies.” Black and white, pacing, sensibility … all kinds of things can impede us from entering a movie because we are used to one kind of film (contemporary) and something old, foreign or both requires some readjustment.

Some require less adjusting than others, however. Anatomy of a Murder is one of them. Despite being a movie from 1959, it feels very modern. Part of it is in the subject matter; part of it is in the way it handles and views that subject matter; it’s partly Duke Ellington’s music for the soundtrack.

Whenever I watch this movie I find myself wondering what is going on behind the eyes of the main characters. I never figure it out. Everyone is so cagey and ambivalent. It’s as if none of them have a moral compass. They exist in a world where that is just excess baggage and only gets in the way.

What follows are the ramblings I made about the movie about ten years ago as I tried get my take on …

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Directed by Otto Preminger

Although I was confused about where exactly Anatomy of a Murder was taking place (Michigan, it seems), it’s a great, enthralling courtroom drama of the noir variety.

It has a great late 50’s black and white look, somewhat similar to Kiss Me Deadly, though this is a far better film. (I wouldn’t take the similarity very far either. It’s just something in the period look they have in common.)

Jimmy Stewart is great in this movie. Some argue it’s his best performance, and there’s something to be said for that.

He has the laconic air and halting speech he’s famous for and it works well here as a kind of strategic approach to getting at the truth of things. It catches others off guard.

He’s a small town lawyer, formerly chief prosecutor (holding the post for ten years). Why he’s no longer in the position isn’t really explained but you get hints his leaving was under a shadow, or at least troubled somehow.

It seems all his character does now is fish, drink and take small, penny-ante cases to pay his bills (which he does badly). Then a big case falls in his lap.

After taking a long time asking questions, mulling things over, and in no apparent hurry to get involved, he finally takes the case and the film really gets underway. (In fact the first portion of the film is a bit slow.)

The case he has is this: a woman (Lee Remick) has been raped. Her soldier husband (Ben Gazzara) has gone out and shot the alleged rapist dead. The soldier is now on trial for murder. Stewart’s job is to defend the soldier. But as he points out to his client, there is really no defense for him … except, possibly, one. The murder being deliberate (an hour after hearing from his wife about the rape), he can’t argue passion. The time element makes it pre-meditated. Gazzara’s only hope is to argue for insanity – an “irrepressible urge.”

There are various complications along the way, including help for the prosecution via the Attorney General’s office in the person of George C. Scott who plays his role with relish, informing it with a kind of conniving smugness.

What really sets Anatomy of a Murder in the noir category is its overarching moral ambivalence. If you pay attention as you watch, you realize that there really are no “good guys” here – not even Stewart, though his performance and the direction align the audience’s sympathies with him.

But he’s defending a man who has committed murder. He is trying to get him off scott free.

You know by what Gazzara says and doesn’t say, and by his performance, that he is guilty. And you know Stewart knows this when he takes the case. The trial is really about playing fast and loose with the law. And both sides in the case do this.

In the case of the woman who was raped, the incident seems to have meant little more to her than stubbing a toe. It’s as if somewhat had given her a quick kiss, not violently raped her.

Of course, her character is a victim in other ways. She’s slatternly and flirtatious and you know from certain scenes, and by the way Remick plays her, she is a woman trapped by abusive men. She’s lonely and seems to gravitate toward men who treat her badly. Her relationship with her husband, Gazzara, suggests domestic violence, though it’s implied and not overtly stated.

At the end of the movie, while there is a resolution (the trial ends) there is no moral resolution. Nothing has changed. Justice has been thrown out the window. The victim will continue to be victimized. While the man who raped her may be dead, she continues on with the one who abuses her.

(It’s interesting to see how her character changes in the film, allows us to see more of who she is, such as her lonliness, then at the film’s end, as she meets Stewart’s character going up the stairs to hear the verdict, she’s back to her previous clothing and flirtatious manner. Again, nothing has changed.)

Despite a few Hollywood elements to lighten the tone at the end, this is a dark film. The hero, Stewart, at the end is little better than those he has been up against.

The movie concludes with a wry look from Jimmy Stewart and a tone of bemused hopelessness as if the director, Otto Preminger, is saying, “That’s people for you. What can you do?”

One last note … The movie’s music was composed by Duke Ellington and it really gives it a unique quality, particularly for the period it was made, and adds to the movie’s overall atmosphere. Ellington also has an uncredited appearance in the movie as Pie Eye, owner of a roadhouse where Jimmy Stewart’s character sometimes goes to play piano.

Lily Damita, Roland Young and This is the Night

Without intending to, I caught This is the Night on TCM last night and I was delightfully surprised. It was funny, curious and also interesting historically in that it was the first full feature movie Cary Grant ever appeared in. It was directed by Frank Tuttle, a man I know best for having directed This Gun For Hire that starred Veronica Lake.

This is the Night (1932)

This is the Night (1932)

Directed by Frank Tuttle

To get the Cary Grant aspect out of the way, you can tell it’s an initial effort. His performance is good sporadically. Often he overplays it, though in one way it works because the film is a farce. You can see, however, the beginnings of what he would later become, especially his comedic skills.

But this movie is really Lily Damita’s and Roland Young’s. (The movie also stars Charles Ruggles and Thelma Todd.)

An athlete (Grant) returns from the Olympics. While he was away, his wife (Todd) has been involved with another man. As that other man, Roland Young must try to cover up the affair. With the help of a friend, Ruggles, he hires a heavily accented actress (Damita) to pretend she’s his wife.

It’s a relationship comedy – quite a funny one – and it is filled with sexual jokes. (The movie was made pre-Code.) For example, a recurring joke in the movie involves Todd whose dress keeps getting removed accidently by the chauffeur/butler. There are verbal jokes as well, such as Damita’s character who doesn’t understand English well, and ends up interpreting hints as, “I live in sin. I am naughty,” when Young tries to tell her to say she’s from Cincinnati.

It’s silly, yes, but lots of fun. It’s not exactly a screwball comedy; it’s a bit too farcical for that. But you can see the beginnings of screwball (just as you can see lingering hints of the silent era in the visual humour, as mentioned in this review).

What I found curious, and a little off-putting, was what I initially thought was a technical mistake in the broadcast but later saw was deliberate. It was this: much of the film occurs in Venice and much of that is at night. Every time the action occurs outside, at night, the screen goes blue.

Yes, it’s a colour that suggests night but in a movie that is otherwise black and white it’s a jarring and unnecessary effect. A quick online look revealed no reference to this so I don’t know if this was something the original movie tried or was added later. But I do know I would remove the effect.

Apart from that, This is the Night is a very fun and funny movie; it even has some nice romantic elements, not to mention Cary Grant’s movie debut. I was glad I found it.

As an aside, Cary Grant would work with Roland Young again a few years later in the movie Topper (1937).

As another aside, Lily Damita was married to Errol Flynn for a number of years and later married to Michael Curtiz. Her Hollywood career was relatively brief. She essentially got out of acting in movies when she married Flynn.

Four movies and a post

Over this holiday period, while I haven’t been posting on any of my sites, neither have I been sitting still.

Over this holiday period, while I haven’t been posting on any of my sites, neither have I been sitting still.

Here on Piddleville, I actually have been adding reviews, though not highlighting them on the home page here.

I hope to rectify that today. So, recently seen …

Holiday Inn (1942)

The movie Holiday Inn is memorable for a number of things, some good, some not so good. To begin with, it brings together a trio made up of Irving Berlin, Bing Crosby and Fred Astaire. Not a bad place to start. The movie itself is a Hollywood soufflé, very light, very unlikely, and quite delightful…

Read more

Unbreakable (2002)

Movies with surprise endings don’t often work well and, even when they do, it’s easy to tire of them quickly. In a sense, they are gimmicky. Done rarely, they’re riveting; done often, they’re tedious. I think M. Night Shyamalan knows this and feels the same way … You get the sense as you watch Unbreakable that he was trying to avoid the surprise ending. On the other hand, you also get the sense that stories of that kind are his natural inclination…

Read more

The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945)

The Bells of St. Mary’s is movie that is very representative of a type of movie Hollywood made in its heyday, very much the way it’s predecessor was, Going My Way. On one hand, it is a type of film that Hollywood has continued to make (like certain Disney films) with varying degrees of success – family oriented and sentimental. On the other hand, it is anachronistic and, for some, nostalgic…

Read more

Now, Voyager (1942)

Here’s a movie that caught me by surprise. It’s another one of those films I went into with little or no expectations. In fact, if anything, I expected it to be a dud. (I had seen a number of older, black and white turkeys recently.) Now, Voyager was wonderful. It’s also an unapologetic soap opera, the kind Hollywood once did so well…

Read more

And now you are up to date. Sort of. More or less. My memory isn’t great; I may have have forgotten something …

Black and white and foreign: cognitive adjustments

When I posted Ikiru as part of 20 Movies a few months ago I made reference to the difficulty many people have with movies that are in black and white and movies that are called foreign (and movies that are both, like Ikiru). I mentioned I understood the difficulty, so I’m going to try to explain myself.

When we say we don’t like a movie that is in black and white we don’t really mean we have a problem with it being a monochromatic movie. What we mean is that generally black and white means an older movie and, with an older movie, most of us have to make cognitive adjustments. As a movie begins, that means an impediment to “getting into” the film.

When we say we don’t like a movie that is in black and white we don’t really mean we have a problem with it being a monochromatic movie. What we mean is that generally black and white means an older movie and, with an older movie, most of us have to make cognitive adjustments. As a movie begins, that means an impediment to “getting into” the film.

(People make black and white movies today but when we see those we understand immediately that it is an aesthetic choice. We accept it as part of the film’s craft. With older movies, black and white means colour wasn’t available as an option or that it was an economic decision. So when we say we don’t like black and white we are saying we’re resistant to the movie’s age.)

What does cognitive adjustment mean?

By cognitive adjustments I simply mean we can’t just watch a movie unfold, as we can with most new release movies. We are use to them being in colour; we are use to certain styles (directing, editing, acting). We are use to a certain cultural sensibility. If a movie doesn’t fit with what we’re use to, we have to adjust to accommodate it.

When we see an older movie we usually see different styles; different sensibilities. For myself, having grown up watching a lot of old movies at home on TV with my mother, I am use to these movies. I don’t need to make any adjustment other than to note it is an older movie.

Were I not the age I am and were I not to have had that experience, I would have to make a big adjustment. Those movies would strike me as odd.

The history of film and of acting can be seen in older movies, more so the older they get. We can see how theatre informed films initially and it was only over time that an awareness of film’s intimacy came about. It took time to realize there was no back row to be played to.

As an example of a cognitive adjustment I had to make, I can look at 2005’s Pride and Prejudice. As I first started watching that movie, I resisted it. The style and pace were not what I associated with Jane Austen. In my head, Jane Austen was associated with her novels and, treated visually, BBC productions (seen on the CBC or PBS). Seeing those kinds of TV treatments from decades like the 1980s and 1990s, I anticipated a slower paced, almost literal approach. The movie I saw in 2005 didn’t line up with that. I had to make an adjustment before being able to appreciate the movie I saw.

I think it is a human trait to resist such adjusting. Our first response is to abandon what we’re encountering and simply move on to a different story, a newer movie.

Reading foreign films — subtitles

It is the same thing with a “foreign” movie. For most of us in North America, foreign means non-English. Those foreign movies come from different cultures and societies, so we need to make a cognitive adjustment. Those movies aren’t in English; many therefore come with sub-titles. So there is a linguistic barrier. The sub-titles present yet another barrier – we have to read to understand the dialogue. When we see the words at the bottom of the screen, our eyes drift down to read the words thus taking our attention from the image that is being presented.

The thing is that with most movies, certainly the good ones, you don’t really need the words. The image tells it all; it’s in the acting. Still, our eyes go to those words and we try to read.

Cognitive adjustments are needed to watch a foreign movie.

This why so many people resist such movies whether they’re black and white, foreign, or both. Interestingly, if you see enough of them you do make those adjustments, unconsciously, and it is relatively easy to watch and appreciate the movies. But it is difficult to initially get past those barriers.

There is a fascinating irony or conundrum in all of this. The best movies always demand cognitive adjustments because they ask us to see things in a new way. They make us change the way we think. The difference with black and white and foreign movies is that they are unintended adjustments. They are not a part of the art of the movie we see. They are adjustments required by time and culture.

A different kind of ghost story

Ghost stories are appropriate for the season, I suppose, but one of my favourites is one of the least ghostly, at least in the “Boo!” sense. It’s The Ghost and Mrs. Muir from 1947.

I remember as a kid watching the TV show that starred Hope Lange. Back then, I had no idea it was based (loosely) on a movie. Then a few years ago I came across the movie. For the record, I’ll take the movie. Just saying.

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir

Directed by Joseph L Mankiewicz

Directed by Joseph L Mankiewicz

If you’re looking to be frightened by a ghost movie, this is not the movie for you. While to some extent it is dressed up in the look of one, it’s a romance, and a melancholy one at that.

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir is a beautiful example of black and white filmmaking. There are some great shots and it’s interesting to see how the movie uses camera technique and other tools to create mood etc. as opposed to using special effects. (For example, Harrison as the ghost appears out of shadows rather than “materializing.”)

The movie is about a recent widow (Gene Tierney) who leaves the oppressive environment of her mother-in-law and sister’s home to take her daughter and live by the sea. She rents a home on the coast, one the real estate man urges her not to take. He reluctantly confesses it is haunted and, because of this, a problem house.

But Tierney’s Lucy Muir falls in love with Gull Cottage and takes it. After a few introductory “haunting” type scenes (less scarey than moody), she meets the ghost, a sea captain played by Rex Harrison. The relationship begins, and so does the real story.

While never explicitly stated (until the end), as an audience we know a romantic relationship is developing – each is falling in love with the other. I think this is because they recognize they share the same independent, uncompromising spirit. One is more overt (the ghost) and the other more restrained (Lucy), but both are informed by individuality.

While never explicitly stated (until the end), as an audience we know a romantic relationship is developing – each is falling in love with the other. I think this is because they recognize they share the same independent, uncompromising spirit. One is more overt (the ghost) and the other more restrained (Lucy), but both are informed by individuality.

Of course, the relationship is doomed since she is a living woman and he is a ghost.

Eventually the captain leaves Mrs. Muir because of this. He wants her to live as a flesh and blood woman and to find love with a living man, though he warns, “… there may be breakers ahead.”

There are and Lucy hits them.

The movie shows us an unusually independent woman. She asserts herself again and again though always with a contradictory sense of apology.

The movie shows us an unusually independent woman. She asserts herself again and again though always with a contradictory sense of apology.

Tierney plays Lucy in a playful way (as the DVD notes say, almost screwball). This quality she gives the character allows the film to show us the passage and transformations of time.

The playfulness gives her a youthful quality in the first half of the film. As the movie progresses, and time passes, this becomes less and less, replaced by an introverted quietness. This interpretation, along with the wonderful score by Bernard Hermann, creates the melancholy feeling the movie’s opening scenes announced.

As time passes and the ghost of the sea captain is no longer in her life, Gene Tierney’s character becomes a lonely woman, almost eccentric.

The film gives us the inevitable Hollywood happy ending but it’s not enough to take away the essential sadness at the heart of the film. Tierney’s Lucy is a wonderful woman but out of step with her environment.

The only person she truly connects with, and who appreciates her independent spirit, is a ghost. The price for her independence is loneliness.

Tierney plays her part perfectly. Harrison, on the other hand, is a little over the top.

The Ghost and Mrs. Muir is a marvellous film. While it contains a lot of humour, it’s primarily a romance, a sweetly melancholic one.

On Amazon:

- The Ghost and Mrs. Muir – Amazon U.S.

- The Ghost and Mrs. Muir – Amazon Canada