Such a study in contrasts! On TCM the other night there were a few William Holden movies running. I tuned in as they were running the marvelous Sunset Boulevard, one of my favourite movies. It was followed by the movie below and … oh my!

Less fun than sobering: Spielberg’s Catch Me

I watched Steven Spielberg’s Catch Me If You Can yet again (third time) over the weekend and now I’m back to my original opinion (as opposed to the one expressed below). Despite being promoted as ‘fun,’ and despite the sixties style ‘fun’ animation of the title sequence, this is really a rather somber story of a young man desperate to save his father from a marriage and life that are disintegrating.

Who dunnit? What did they do? Who cares? – Anatomy of a Murder

It’s Day 4 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. And if you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down this page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

What I like about Anatomy of a Murder is that every so often a friend will say something like, “… This movie I saw on TV was so good …” As they describe it I realize what movie they mean and remark, “That’s Anatomy of a Murder.”

What I like about Anatomy of a Murder is that every so often a friend will say something like, “… This movie I saw on TV was so good …” As they describe it I realize what movie they mean and remark, “That’s Anatomy of a Murder.”

“Yeah! That’s what it was called!”

I mention this because many of these people usually have to make what I called cognitive adjustments in a post not long ago. They don’t like “old movies.” Black and white, pacing, sensibility … all kinds of things can impede us from entering a movie because we are used to one kind of film (contemporary) and something old, foreign or both requires some readjustment.

Some require less adjusting than others, however. Anatomy of a Murder is one of them. Despite being a movie from 1959, it feels very modern. Part of it is in the subject matter; part of it is in the way it handles and views that subject matter; it’s partly Duke Ellington’s music for the soundtrack.

Whenever I watch this movie I find myself wondering what is going on behind the eyes of the main characters. I never figure it out. Everyone is so cagey and ambivalent. It’s as if none of them have a moral compass. They exist in a world where that is just excess baggage and only gets in the way.

What follows are the ramblings I made about the movie about ten years ago as I tried get my take on …

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Directed by Otto Preminger

Although I was confused about where exactly Anatomy of a Murder was taking place (Michigan, it seems), it’s a great, enthralling courtroom drama of the noir variety.

It has a great late 50’s black and white look, somewhat similar to Kiss Me Deadly, though this is a far better film. (I wouldn’t take the similarity very far either. It’s just something in the period look they have in common.)

Jimmy Stewart is great in this movie. Some argue it’s his best performance, and there’s something to be said for that.

He has the laconic air and halting speech he’s famous for and it works well here as a kind of strategic approach to getting at the truth of things. It catches others off guard.

He’s a small town lawyer, formerly chief prosecutor (holding the post for ten years). Why he’s no longer in the position isn’t really explained but you get hints his leaving was under a shadow, or at least troubled somehow.

It seems all his character does now is fish, drink and take small, penny-ante cases to pay his bills (which he does badly). Then a big case falls in his lap.

After taking a long time asking questions, mulling things over, and in no apparent hurry to get involved, he finally takes the case and the film really gets underway. (In fact the first portion of the film is a bit slow.)

The case he has is this: a woman (Lee Remick) has been raped. Her soldier husband (Ben Gazzara) has gone out and shot the alleged rapist dead. The soldier is now on trial for murder. Stewart’s job is to defend the soldier. But as he points out to his client, there is really no defense for him … except, possibly, one. The murder being deliberate (an hour after hearing from his wife about the rape), he can’t argue passion. The time element makes it pre-meditated. Gazzara’s only hope is to argue for insanity – an “irrepressible urge.”

There are various complications along the way, including help for the prosecution via the Attorney General’s office in the person of George C. Scott who plays his role with relish, informing it with a kind of conniving smugness.

What really sets Anatomy of a Murder in the noir category is its overarching moral ambivalence. If you pay attention as you watch, you realize that there really are no “good guys” here – not even Stewart, though his performance and the direction align the audience’s sympathies with him.

But he’s defending a man who has committed murder. He is trying to get him off scott free.

You know by what Gazzara says and doesn’t say, and by his performance, that he is guilty. And you know Stewart knows this when he takes the case. The trial is really about playing fast and loose with the law. And both sides in the case do this.

In the case of the woman who was raped, the incident seems to have meant little more to her than stubbing a toe. It’s as if somewhat had given her a quick kiss, not violently raped her.

Of course, her character is a victim in other ways. She’s slatternly and flirtatious and you know from certain scenes, and by the way Remick plays her, she is a woman trapped by abusive men. She’s lonely and seems to gravitate toward men who treat her badly. Her relationship with her husband, Gazzara, suggests domestic violence, though it’s implied and not overtly stated.

At the end of the movie, while there is a resolution (the trial ends) there is no moral resolution. Nothing has changed. Justice has been thrown out the window. The victim will continue to be victimized. While the man who raped her may be dead, she continues on with the one who abuses her.

(It’s interesting to see how her character changes in the film, allows us to see more of who she is, such as her lonliness, then at the film’s end, as she meets Stewart’s character going up the stairs to hear the verdict, she’s back to her previous clothing and flirtatious manner. Again, nothing has changed.)

Despite a few Hollywood elements to lighten the tone at the end, this is a dark film. The hero, Stewart, at the end is little better than those he has been up against.

The movie concludes with a wry look from Jimmy Stewart and a tone of bemused hopelessness as if the director, Otto Preminger, is saying, “That’s people for you. What can you do?”

One last note … The movie’s music was composed by Duke Ellington and it really gives it a unique quality, particularly for the period it was made, and adds to the movie’s overall atmosphere. Ellington also has an uncredited appearance in the movie as Pie Eye, owner of a roadhouse where Jimmy Stewart’s character sometimes goes to play piano.

For the Love of Film (Noir): This Gun For Hire

Today the For the Love of Film (Noir) blogathon begins and I decided rather than burble about the genre, which can be as murky as the streets and lives its films tend to articulate, I’d post something about a specific noir, one that stars an actor who really hit his stride, as far as fame goes, with the genre and this particular movie, This Gun For Hire. The actor, of course, is Alan Ladd.

The blogathon runs thru to February 21st with the goal of raising money to restore a specific movie, The Sound of Fury (1950, aka Try and Get Me). I love the brief description on IMDb, “A man down on his luck falls in with a criminal. After a senseless murder, the two are lynched.” If you’re inclined to pitch in, please do. You can . And now, on with …

This Gun For Hire (1942)

Directed by Frank Tuttle

I came upon a review of This Gun For Hire that complained about it being viewed as film noir. The reviewer argued it was not; it was pulp. The first thing I thought was, “Aren’t all the best film noirs pulp?” My second thought was a sigh because film noir is so idiosyncratic in its definition. Everyone has their own idea of what it is.

For me, this movie is film noir. Regardless of whether it is or not, the important thing is it’s a wholly captivating movie, thanks largely to Alan Ladd’s portrayal of Raven.

Of course there is also some pretty brisk direction from Frank Tuttle and a good script.

Billing aside, this is Alan Ladd’s movie. He is the star. As good as they are, you could replace Robert Preston and Veronica Lake and not much would change. Replace Ladd and I suspect you would have a different movie and perhaps not as good.

Amid the murder and mayhem of the film, it is the story of Raven: what he does and why he does it. In other words, it’s about who he is. In the first few minutes, we see a man who uses a gun and, given the title, we infer it is for nothing good.

But we quickly see him with a cat and a moment of softening. He cares for the cat; there is tenderness. Raven then leaves the room and almost immediately we see a woman come in to tidy it. She shoos the cat away crossly and Raven steps back into the room.

Now we see what the gun is about. We see the Raven the world must deal with. He strikes the woman, tears her dress and forces her out of the room.

It is less what he does than it is how he does it: quick, brutal and unrepentant. The tenderness he has for cats is not extended to people. The opening, then, tells us what we need to know about the character. From here, the story’s engine kicks in. The opening is a great example of exposition. It provides essential information, and in a riveting way, so we can understand what is to follow.

What follows is standard pulp/film noir material. Raven is a hired killer. He does a job. Then he is shafted by the man who hired him. He’s paid with marked, stolen money. As soon as he spends some of it, the police are after him and he immediately recognizes what has happened. Now his goal is simple: kill the people who set him up. And he is nothing if not focused.

It is not that simple, however. There are complications. But this is the essential story: Raven on a mission to kill the people who set him up and how his character is revealed and alters in the process. Even the ostensible stars, Preston and Lake, are secondary to Ladd’s Raven. They are tools for revealing his character.

As with the similar (though not nearly as good) movie, Lucky Jordan, the complications involve the Second World War, selling vital material to the enemy, and patriotic pleas. Raven cares only for himself (as does Jordan) and it’s the role of Lake to persuade him to see the larger picture and care for the country which means other people.

What she is up against is a man whose background was as brutal as he has become and that has defined him and how he sees the world. The world he now inhabits confirms his view. Yet we know there is something human in him from how he relates to cats and we understand later in the film why he is as he is in a scene where he describes his childhood. Despite his callousness and violence, we care about him.

Although he was in countless movies prior to this one, This Gun For Hire was the first time Alan Ladd starred in a movie, although he was sitting in the back row as far as the billing went. I can understand why he hadn’t been noticed prior to this though. From the few movies I’ve seen him in, Ladd seems one of the quietest, most understated actors I’ve seen. Few actors express anger and melancholy as well as he does or as naturally.

Frank Tuttle, a kind of journeyman director who cranked out movies for the studio, excels here, perhaps because of the script, perhaps because of the work of cinematographer John F. Seitz, or maybe because he was a meat and potatoes director. The movie is simply and quickly directed and that is one of its virtues.

Call it a crime film, call it pulp, call it what you will, to me this is a great example of noir and regardless of genre a thoroughly compelling movie. As you may have guessed, I liked it a lot.

Guy movie with Gable and gravitas

I’m always astonished when I notice the movies Robert Wise has been involved with, particularly as director. I tend to think of him as a “meat and potatoes” kind of director because I don’t notice him. His movies never draw attention to themselves as movies; they’re simply stories told well.

As an editor, he worked with Orson Welles on Citizen Kane. As director, he’s done movies like The Sound of Music, The Haunting, West Side Story (as co-director) and the movie below, Run Silent, Run Deep.

Run Silent, Run Deep (1958)

Run Silent, Run Deep (1958)

Directed by Robert Wise

I saw an interview with the actor Laurence Fishburne the other day in which he was speaking of various influences when he was young. At one point, he brought up the movie Run Silent, Run Deep and Clark Gable. What struck him in the movie was Gable’s gravitas. I immediately thought, “Yes, that is the perfect word for it.”

Fishburne brought this up because Gable would have been in his late 50s when he made the film.

He was not playing the young, dashing, romantic figure of movies like Gone With the Wind. And he wasn’t playing the great white hunter of Mogambo, made only five years earlier.

He does, however, play a “manly man,” which would have had great appeal for him, from the little I know of Gable.

Run Silent, Run Deep is a guy movie. There are really only two female roles in the movie: a very small part as Gable’s wife (Mary LaRoche) and a pin-up poster. It’s all guys and for the most part they are confined in a submarine. Despite that, it’s a good movie. Actually, it is because of that it is a good movie. It knows what it is about and its focus doesn’t waver.

Run Silent, Run Deep is a guy movie. There are really only two female roles in the movie: a very small part as Gable’s wife (Mary LaRoche) and a pin-up poster. It’s all guys and for the most part they are confined in a submarine. Despite that, it’s a good movie. Actually, it is because of that it is a good movie. It knows what it is about and its focus doesn’t waver.

Gable is submarine Commander Richardson, a man who, as we see in the opening scenes, loses the sub he commands when it is sunk by a Japanese destroyer, one that acquires a kind of legendary status because it is so successful in sinking U.S. subs. (The movie is set during World War II.)

After a long wait, Richardson gets another command (one he has specifically gone after). Unfortunately, that sub’s crew thinks their first officer, Lieutenant Jim Bledsoe (Burt Lancaster) is getting the command, as does Bledsoe. When Richardson comes aboard to take over, it is to a resentful crew and first officer.

Things don’t improve when he makes the crew go through the same drill repeatedly, obsessed with shaving seconds off the time it takes to dive and launch torpedoes. It further degrades when this new commander appears to avoid going after Japanese ships. It strikes the crew as cowardly.

It turns out the commander has plans: against orders, he intends to take the sub into dangerous waters and sink the unsinkable ship that is taking out all the U.S. subs, including Commander Richardson’s previous submarine.

It’s a simple, direct story and won’t ever be accused of being overly sophisticated. But it’s virtue is its simplicity and directness. Director Robert Wise has left nothing necessary out and has put nothing unnecessary in.

Gravitas, like the word gravity, comes from the Latin word “gravis” which means seriousness or weightiness. Gable communicates it wonderfully. Lancaster does to a degree too, though in a different way. Between the two actors, you get a nicely dramatic contrast.

Gravitas, like the word gravity, comes from the Latin word “gravis” which means seriousness or weightiness. Gable communicates it wonderfully. Lancaster does to a degree too, though in a different way. Between the two actors, you get a nicely dramatic contrast.

Gable, outside moments of command, speaks in a drawling, friendly manner. In moments of command, he’s brusque and direct. Lancaster, on the other hand, with his character’s resentment, speaks in a clipped fashion. He also communicates a sense of simmering anger that only his naval discipline keeps in control.

It’s the dynamic between the two characters that really propels this movie, though a straightforward, determined plot nicely aids it.

I’ve seen this movie several times over the years and have liked it every time. Initially, I was a young boy and thought it was cool because it had submarines and torpedoes. Grown up, I like it because it is just a good, well told story.

Ernst Lubitsch and his lustfully troubled Paradise

Without really planning too, I’ve found myself watching the movies of Ernst Lubitsch. A few nights ago it was The Shop Around the Corner. Last night it was Trouble in Paradise. I had seen both before, at least once each. What I find interesting is that the more I see them, the more I like them. The first time around you miss how well constructed they are because they evolve so seamlessly. So I definitely recommend seeing them at least twice.

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

One of the finest romantic comedies ever made, and one that in many ways created a template and set standards for later romantic comedies (while also looking ahead to the screwball comedies to come), is Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise, made in 1932.

With a single film, American cinema suddenly grew up. In many ways, it’s the most adult film Hollywood has ever made. (Not long after, production codes were put in place and much of what is in Trouble in Paradise would not have been allowed.)

Prior to Lubitsch’s first nonmusical American film, the sophisticated manner and style of this movie hadn’t been seen, not on this side of the Atlantic. Nor had this degree of elevated wit or sexual play.

Much is made of the “Lubitsch touch,” and there certainly is such a thing. While a bit hard to define precisely, it has a great deal to do with a European sensibility, one not informed by a Puritan cultural background. It has to do with wit and sophistication and adult romance.

Much is made of the “Lubitsch touch,” and there certainly is such a thing. While a bit hard to define precisely, it has a great deal to do with a European sensibility, one not informed by a Puritan cultural background. It has to do with wit and sophistication and adult romance.

Here, adult means playful, well-mannered and tinged by a degree of melancholy. Trouble in Paradise is a perfect example of this.

The movie is about two charming thieves, their love for one another, as well as their enjoyment of their craft. It’s about the playfulness between them, and the woman whom they choose as their mark.

Herbert Marshall is the thief Gaston Monescu. He charms his way into the life of Mariette Colet (Kay Francis) in order to steal her money. His love, the pickpocket Lily (Miriam Hopkins), is his accomplice.

But this is what Hitchcock would call the McGuffin. The movie is really about the triangle that develops as Gaston becomes romantically enchanted by Mariette just as she falls in love with him. All the while, Lily is still there and still loves Gaston, just as he still loves her.

But this is what Hitchcock would call the McGuffin. The movie is really about the triangle that develops as Gaston becomes romantically enchanted by Mariette just as she falls in love with him. All the while, Lily is still there and still loves Gaston, just as he still loves her.

Lubitsch’s direction is nothing less than wonderful here. One of the qualities that characterize his films, especially in Trouble in Paradise, is his refusal to be obvious about anything. He tells his story through indirection and implication, rarely being overt.

This is particularly true with the way he implies sexuality and its encounters without ever stating, much less showing, anything. It is part of the film’s playful wit and charm and adult quality. Equally adult is the absence of any salacious sense. There is no sense of “nudge-nudge, wink-wink” here.

Yet, essentially, the film is about lust, Gaston’s and Mariette’s.

As Peter Bogdanovich mentions in his introduction to the Criterion DVD of the film, it’s a wonder this was ever made in Hollywood, particularly when we see where we are today.

As Peter Bogdanovich mentions in his introduction to the Criterion DVD of the film, it’s a wonder this was ever made in Hollywood, particularly when we see where we are today.

While the troubled triangle of Gaston, Mariette and Lily plays out, the movie also gives us the ineffectual efforts of the Major (Charlie Ruggles) and Francois (Edward Everett Horton), two of Mariette’s luckless suitors. Their ineptness and pretensions provide a nice comedic counterpoint to the sophistication of Gaston.

Much of what Lubitsch does isn’t noticed on first viewing the movie. It is too seamless and fluid. The plot unfolds too effortlessly. It’s only on seeing a second or third or fourth time you see the small details he attends to and just how cleverly the movie is constructed.

In cinema terms, Ernst Lubitsch was a magician. Much of what he does is a kind of sleight of hand — verbal and visual. His movies, like Trouble in Paradise, are mature, charming and absolutely wonderful.

See:

Lily Damita, Roland Young and This is the Night

Without intending to, I caught This is the Night on TCM last night and I was delightfully surprised. It was funny, curious and also interesting historically in that it was the first full feature movie Cary Grant ever appeared in. It was directed by Frank Tuttle, a man I know best for having directed This Gun For Hire that starred Veronica Lake.

This is the Night (1932)

This is the Night (1932)

Directed by Frank Tuttle

To get the Cary Grant aspect out of the way, you can tell it’s an initial effort. His performance is good sporadically. Often he overplays it, though in one way it works because the film is a farce. You can see, however, the beginnings of what he would later become, especially his comedic skills.

But this movie is really Lily Damita’s and Roland Young’s. (The movie also stars Charles Ruggles and Thelma Todd.)

An athlete (Grant) returns from the Olympics. While he was away, his wife (Todd) has been involved with another man. As that other man, Roland Young must try to cover up the affair. With the help of a friend, Ruggles, he hires a heavily accented actress (Damita) to pretend she’s his wife.

It’s a relationship comedy – quite a funny one – and it is filled with sexual jokes. (The movie was made pre-Code.) For example, a recurring joke in the movie involves Todd whose dress keeps getting removed accidently by the chauffeur/butler. There are verbal jokes as well, such as Damita’s character who doesn’t understand English well, and ends up interpreting hints as, “I live in sin. I am naughty,” when Young tries to tell her to say she’s from Cincinnati.

It’s silly, yes, but lots of fun. It’s not exactly a screwball comedy; it’s a bit too farcical for that. But you can see the beginnings of screwball (just as you can see lingering hints of the silent era in the visual humour, as mentioned in this review).

What I found curious, and a little off-putting, was what I initially thought was a technical mistake in the broadcast but later saw was deliberate. It was this: much of the film occurs in Venice and much of that is at night. Every time the action occurs outside, at night, the screen goes blue.

Yes, it’s a colour that suggests night but in a movie that is otherwise black and white it’s a jarring and unnecessary effect. A quick online look revealed no reference to this so I don’t know if this was something the original movie tried or was added later. But I do know I would remove the effect.

Apart from that, This is the Night is a very fun and funny movie; it even has some nice romantic elements, not to mention Cary Grant’s movie debut. I was glad I found it.

As an aside, Cary Grant would work with Roland Young again a few years later in the movie Topper (1937).

As another aside, Lily Damita was married to Errol Flynn for a number of years and later married to Michael Curtiz. Her Hollywood career was relatively brief. She essentially got out of acting in movies when she married Flynn.

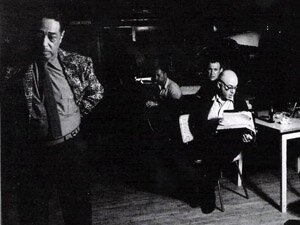

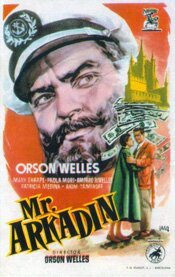

Mr. Arkadin – another fine mess

I’ve noticed Orson Welles had a thing for looking with slightly bowed head up from under his eyebrows. He uses it a lot in Mr. Arkadin, though I suspect it’s deliberate with an intention of parody, perhaps of himself. It’s hard to know with any certainty what his intentions were with that movie since it is an incomplete and irresistible mess.

Mr. Arkadin (1955), aka Confidential Report

Mr. Arkadin (1955), aka Confidential Report

Sometimes too much is too much and with Orson Welles’ Mr. Arkadin we have an good example of this. It’s too much of so many things (which in some ways is the film’s point, if it has one at all). To begin with, I have the Criterion 3-disc set, which means I don’t just have the movie; I have three versions of it.

The result has been that it has been sitting on my shelf for ages because I couldn’t decide which version to watch. I finally have arbitrarily choosen the second (or Confidential Report) version for no reason other than that I read somewhere that it was the one with the best picture quality.

If you know anything about Mr. Arkadin then you know it is a movie Welles never finished, so there is no definitive version. The movie was taken from him and others have completed it, in one fashion or another, over the years. The most recent version is the Criterion “comprehensive” version, a scholarly approach to restoring the movie in order to get a version as close to what we dimly know Welles was attempting, though no one really knows. (This last version is also the longest coming in at roughly 110 minutes.)

Not only do the various versions include and/or exclude various scenes, the sequence of the scenes also varies depending on the version. It was always intended to use flashbacks and a degree of disorientation for the audience, but the degree changes. The Confidential Report version may be the one that comes closest to being comprehensible, but that is open to debate.

Not only do the various versions include and/or exclude various scenes, the sequence of the scenes also varies depending on the version. It was always intended to use flashbacks and a degree of disorientation for the audience, but the degree changes. The Confidential Report version may be the one that comes closest to being comprehensible, but that is open to debate.

All of that aside, we’re still left with a movie to watch – one of its versions, at least. What’s the word on that? Is it any good?

Not really. It’s a mess, actually. I had thought I had never seen the movie previously but almost as soon as it started a voice in my head said, “Oh, that movie …” I had seen it before; it didn’t have much impact, largely because it isn’t a good movie.

It is, however, a fascinating movie, at least if Orson Welles intrigues you. It’s hard to know just how serious Welles was in making this work. There is a high level of playfulness in the movie. Is it because he’s just having fun, mocking himself even, but not too serious about the production? Or is it an aspect of a serious film?

It is, however, a fascinating movie, at least if Orson Welles intrigues you. It’s hard to know just how serious Welles was in making this work. There is a high level of playfulness in the movie. Is it because he’s just having fun, mocking himself even, but not too serious about the production? Or is it an aspect of a serious film?

Mr. Arkadin is, in some ways, almost a parody of Citizen Kane with its story of a mysterious, powerful man and the puzzle the movie creates around his identity.

Amongst other things, Welles distorts himself physically, at least in a sense, with his wig and fake beard and the obviousness of them, as well as his clothes in the movie. It’s as if he is deliberately focusing in on himself for the purpose of self-mockery. Was that the intent?

As for the puzzle the movie creates, that is largely responsible for the mess that the movie is as it tries to both resolve itself and remain oblique at the same time. Compounding this problem is fact that a puzzle, to be a real puzzle, must have a way to resolve. I suspect neither Welles nor anyone else ever truly figured that one out. As a result, the movie flounders in confusion because there really isn’t anywhere for it to go other than down another blind alley.

Yet the movie is dazzling in its confusion. And bizarre. Odd camera angles, over-dubbed dialogue (that changes from version to version), mix and match scenes … Yes, very odd.

I hadn’t planned to, but I watched Mr. Arkadin a day or two after having watched another of Welles’ movies, The Stranger. They make for an interesting contrast. The latter film is one Welles thought least highly of. It was an exercise in proving he could make a commercial film and, as a result, may be his most coherent. Mr. Arkadin is the exact opposite. It’s famously incoherent.

But for something that is a mess, it sure has style and humour and some fabulous scenes.