Today the For the Love of Film (Noir) blogathon begins and I decided rather than burble about the genre, which can be as murky as the streets and lives its films tend to articulate, I’d post something about a specific noir, one that stars an actor who really hit his stride, as far as fame goes, with the genre and this particular movie, This Gun For Hire. The actor, of course, is Alan Ladd.

The blogathon runs thru to February 21st with the goal of raising money to restore a specific movie, The Sound of Fury (1950, aka Try and Get Me). I love the brief description on IMDb, “A man down on his luck falls in with a criminal. After a senseless murder, the two are lynched.” If you’re inclined to pitch in, please do. You can . And now, on with …

This Gun For Hire (1942)

Directed by Frank Tuttle

I came upon a review of This Gun For Hire that complained about it being viewed as film noir. The reviewer argued it was not; it was pulp. The first thing I thought was, “Aren’t all the best film noirs pulp?” My second thought was a sigh because film noir is so idiosyncratic in its definition. Everyone has their own idea of what it is.

For me, this movie is film noir. Regardless of whether it is or not, the important thing is it’s a wholly captivating movie, thanks largely to Alan Ladd’s portrayal of Raven.

Of course there is also some pretty brisk direction from Frank Tuttle and a good script.

Billing aside, this is Alan Ladd’s movie. He is the star. As good as they are, you could replace Robert Preston and Veronica Lake and not much would change. Replace Ladd and I suspect you would have a different movie and perhaps not as good.

Amid the murder and mayhem of the film, it is the story of Raven: what he does and why he does it. In other words, it’s about who he is. In the first few minutes, we see a man who uses a gun and, given the title, we infer it is for nothing good.

But we quickly see him with a cat and a moment of softening. He cares for the cat; there is tenderness. Raven then leaves the room and almost immediately we see a woman come in to tidy it. She shoos the cat away crossly and Raven steps back into the room.

Now we see what the gun is about. We see the Raven the world must deal with. He strikes the woman, tears her dress and forces her out of the room.

It is less what he does than it is how he does it: quick, brutal and unrepentant. The tenderness he has for cats is not extended to people. The opening, then, tells us what we need to know about the character. From here, the story’s engine kicks in. The opening is a great example of exposition. It provides essential information, and in a riveting way, so we can understand what is to follow.

What follows is standard pulp/film noir material. Raven is a hired killer. He does a job. Then he is shafted by the man who hired him. He’s paid with marked, stolen money. As soon as he spends some of it, the police are after him and he immediately recognizes what has happened. Now his goal is simple: kill the people who set him up. And he is nothing if not focused.

It is not that simple, however. There are complications. But this is the essential story: Raven on a mission to kill the people who set him up and how his character is revealed and alters in the process. Even the ostensible stars, Preston and Lake, are secondary to Ladd’s Raven. They are tools for revealing his character.

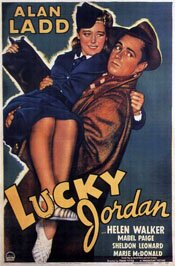

As with the similar (though not nearly as good) movie, Lucky Jordan, the complications involve the Second World War, selling vital material to the enemy, and patriotic pleas. Raven cares only for himself (as does Jordan) and it’s the role of Lake to persuade him to see the larger picture and care for the country which means other people.

What she is up against is a man whose background was as brutal as he has become and that has defined him and how he sees the world. The world he now inhabits confirms his view. Yet we know there is something human in him from how he relates to cats and we understand later in the film why he is as he is in a scene where he describes his childhood. Despite his callousness and violence, we care about him.

Although he was in countless movies prior to this one, This Gun For Hire was the first time Alan Ladd starred in a movie, although he was sitting in the back row as far as the billing went. I can understand why he hadn’t been noticed prior to this though. From the few movies I’ve seen him in, Ladd seems one of the quietest, most understated actors I’ve seen. Few actors express anger and melancholy as well as he does or as naturally.

Frank Tuttle, a kind of journeyman director who cranked out movies for the studio, excels here, perhaps because of the script, perhaps because of the work of cinematographer John F. Seitz, or maybe because he was a meat and potatoes director. The movie is simply and quickly directed and that is one of its virtues.

Call it a crime film, call it pulp, call it what you will, to me this is a great example of noir and regardless of genre a thoroughly compelling movie. As you may have guessed, I liked it a lot.

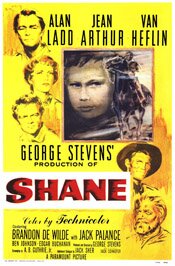

Shane (1953)

Shane (1953) Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time.

Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time. Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence.

Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence. Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained.

Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained. Lucky Jordan (1942)

Lucky Jordan (1942) He eventually finds himself in the Army where he is contemptuous of it. He goes AWOL and finally deserts. He comes upon secret military plans which another gangster (Sheldon Leonard as Slip Moran) has plans to sell to the Nazi’s. Slip also has plans to take over from Lucky.

He eventually finds himself in the Army where he is contemptuous of it. He goes AWOL and finally deserts. He comes upon secret military plans which another gangster (Sheldon Leonard as Slip Moran) has plans to sell to the Nazi’s. Slip also has plans to take over from Lucky. The movie ends with an inevitable patriotic finish, the final scene feeling like an obligatory add-on. But in the process of getting from start to end, it tells a good story about a particular character, Lucky Jordan. In the process, it doesn’t simply use a self-centred individual. The script gives some explanation for why he is as he is by giving some detail on his background.

The movie ends with an inevitable patriotic finish, the final scene feeling like an obligatory add-on. But in the process of getting from start to end, it tells a good story about a particular character, Lucky Jordan. In the process, it doesn’t simply use a self-centred individual. The script gives some explanation for why he is as he is by giving some detail on his background.