You might think focusing on the story when making a movie would be a no-brainer but, as quite a few movies seem to illustrate, it’s not. One of things I’ve always liked about Clint Eastwood is his insistence on the story first, foremost, almost exclusively.

American Rebel: Eastwood bio a disappointing read

While I remember the song from Rawhide I don’t recall ever having seen it. For me, Clint Eastwood’s career would have begun with A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

Sergio Leone and a good, odd western

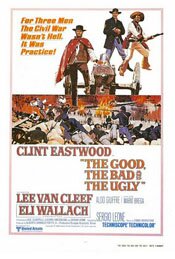

I’m currently reading Marc Eliot’s Clint Eastwood: American Rebel and it inevitably got me thinking about the earlier Eastwood movies, the spaghetti westerns, including The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Below is my lengthy rambling about it from quite a while ago (2000?). For what it is worth …

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Directed by Sergio Leone

One of the best, and oddest, westerns ever made is The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo). It’s hard to imagine anyone making a movie like this today. It’s too long (it would be argued). Some of the scenes, even shots, are too long. Gee, it takes 30 minutes to introduce the three primary characters. What’s that about?

Continue reading

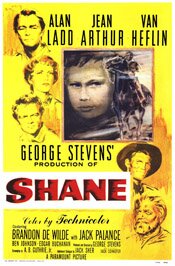

Is Shane too aware of itself as a western?

I wrote the bit below about 8 to 10 years ago after seeing Shane for the first time. It’s strictly a gut response and an attempt to figure out that gut response. But I think it may be time for me to re-watch this movie and see if I still have the same reaction or if I can finally see what many others see in the movie.

Shane (1953)

Shane (1953)

Directed by George Stevens

I’ve never seen Shane before. I haven’t discussed it in a film studies class. I haven’t spent hours in bars or cafes talking about it. I just like westerns, knew it was considered one of the best, and finally decided to watch it. So my reaction to it is, in many ways, fresh and not particularly tainted by what others think of it.

Gut response? I was a bit bored. But I’m not so sure it’s a fault of the movie so much as it’s a problem that the film’s sensibilities are of a time when they were not as frenetic as they are now. People were a bit more open to a more leisurely pace.

On the other hand, some of the problems were not just sensibility and the film’s tempo. Shane suffers, I think, from being a little too self-conscious. It’s a little too aware of the western genre, of its place in it, and of its purpose, which is too comment on the genre and film violence.

Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time.

Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time.

Shane arrives at a Wyoming homestead as a drifter. He stays for a while with people who are oppressed by cattlemen trying to take over their land. He is distant but suggests strength. Men and women admire and respect him, children hero-worship him. Eventually troubles with the cattlemen come to a head and it is Shane who faces them down.

Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence.

Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence.

The result is a lot of time spent on creating the non-violent world represented by Marion (Jean Arthur) and her husband-farmer played by Van Heflin. (He, by the way, is absolutely perfect in this role; his performance is nothing less than great.)

Unfortunately, the family life, the life of hard work, is not particularly interesting. To appreciate the value of this kind of life you have to live it. To watch it is to go to sleep.

We get to see Shane watching this life, and see his longing for it (an essential element in the film) but again, it’s a bit of a snooze. It’s one of the hardest tasks an artist can set him or herself: to make the lives of nice people interesting for an audience. It is seldom done successfully.

Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained.

Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained.

This is all just gut reaction but I really think Shane falls short primarily for one reason: it’s a movie for the intellect and not for the gonads. Westerns are meat-and-potatoes films. They are best when they’re simple. They’re best when they follow formulas. They are best when they tell you things that are true viscerally, not via the brain.

(Note: This review was written back around 2003. It was my initial response to my first viewing of the movie.)

20 movies: Tombstone (1993)

I can think of no better place to start my list of twenty movies than with one of my favourite kinds of movies, the western, and specifically one of my favourite westerns, Tombstone from 1993. If you want something to watch this summer, try this one.

While there are many aspects to the movie that are excellent, the one that truly stands out is Val Kilmer’s portrayal of Doc Holliday. If you have never seen the movie, or if you haven’t seen it in a few years, it’s time to watch one of the great performances. In some ways, Tombstone is a variation of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Kilmer’s Holliday is a new take on John Wayne’s Tom Doniphon.

Here’s my review of the movie that I wrote a few years ago:

Tombstone

directed by George P. Cosmatos

This movie frustrates me because I don’t know what to write. It’s one of the best westerns I’ve ever seen and, to be truthful, that’s really all I have to say about it.

Of course, I love westerns. But I’m not sure why. I think it’s because of the simplicity of the stories and the fact that they are, essentially, all mythical.

I suppose you could say this about all movies but westerns, in particular, access mythic elements and use them to engage us. They really are the same damn story played over and over again.

The best westerns do this; the least successful ones try to play with the genre.

Having said that, I think director George P. Cosmatos and writer Kevin Jarre do play with the genre just a tad … but they rigidly adhere to the essential elements. For example, one of the staples of westerns is the opening when the bad guys come in and do something really, really bad. I can’t think of a single Clint Eastwood western that doesn’t do this. What this does is immediately set the context of the movie – a wild and lawless landscape that is crying out for order.

The next step is to introduce us to the good guy (or guys) who are reluctantly drawn in and eventually save the day.

Simple stuff, and exactly what Tombstone does.

But within this simple framework, Cosmatos and Jarre do much more. Chiefly, they give us characters with much greater delineation and far more contradictions that the average B western.

In particular, we get the incredible performance of Val Kilmer as Doc Holliday. It’s not the usual Doc Holliday; this one is true to history and, within that, Kilmer gives us perfect and unexpected nuances.

And while the Doc Holliday character may be the one we walk away remembering best, Kurt Russell’s Wyatt Earp is equally masterful. He’s less interesting only because his character is the good guy. But he has his own contradictions and, more importantly, it’s the apparent paradox of his relationship with Doc Holliday around which the movie revolves and succeeds.

There are, of course, a few minor problems with the film, as with all movies. For example, there is the scene when Bill Paxton as the youngest Earp, Morgan, is shot and Kurt Russell is with him. Russell’s hands and arms are covered in blood. He runs his hands over Paxton’s forehead – he seems to touch just about everyone in the place, including himself – yet no blood rubs off on anyone. Huh? How’d that happen?

But it’s a quibble. The movie is pure western, from setting to music to story. It also avoids that sepia nonsense so many westerns have. Rather, they have shot this movie to show the colour of the mythic west and it’s a tremendous relief to see a western with this much confidence in itself as a western.

Tombstone (the trailer)

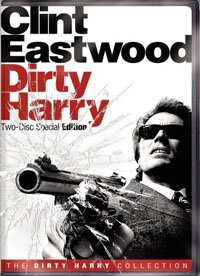

Dirty Harry: should I like it as much as I do?

I’ve always found Dirty Harry a troubling movie. Well, almost all of the earlier, image making movies of Clint Eastwood have been troubling to me, but Dirty Harry tops my list. The reason is simple: from the first time I saw it, I’ve loved the movie but I felt that I shouldn’t.

I’ve always found Dirty Harry a troubling movie. Well, almost all of the earlier, image making movies of Clint Eastwood have been troubling to me, but Dirty Harry tops my list. The reason is simple: from the first time I saw it, I’ve loved the movie but I felt that I shouldn’t.

The conflict is easy to explain. The movie is manipulated to have you cheering for Harry so when, as in a western, the final showdown happens, there’s a cathartic moment, like scoring the winning touchdown on the last play of the game. But then you do a kind of mental double take: this guy with the big gun is actually ignoring the law, being as bad as the bad guys, and feeling justified about it because, well, they’re bad guys and he’s fighting for the good guys.

Harry is essentially a vigilante and in the movie, by creating a perverted, killing bad guy (“Scorpio”), you inevitably root for him because the emotion carries you along and your thinking side is turned off, in a manner of speaking. In his review, Roger Ebert argues that it’s essentially a fascist film, and this may be true, although I think the final scene with Harry tossing his badge in the water could be construed as meaning he’s outside the law now, no different than the criminals he’s been hunting down. It may be the movie wants you to cheer for Harry so it can then say, “Now think seriously about what you’re really cheering for.”

There are lots of people who write about Harry’s appeal to the conservative right, at least of the time (1971), and a frustration with liberal approaches to crime – respecting individual rights, in this case the criminal’s, and abandoning victims. And this may be true, too, though it should be pointed out that operating beyond the law, ignoring victims, is not something to be found on the far right of things. Some, at the far left, have had no qualms about victims when they’ve initiated a violent act for their cause. It’s an attitude that occurs at the far end of things, at extremes, be they left or right.

But what about the movie? Dirty Harry always initiates discussion about the politics of the film and often the movie itself gets overlooked.

First off, I see it as an urban western, and loving westerns that may explain why I like it so much. Harry’s a loner, operating on his own (often to the exasperation of his superiors). He gets little help – some, but not a lot – and he’s after a really bad guy. So it’s framed like a moral tale, the way westerns are … but this leads us into the politics again. It is a moral tale but one a lot more subtle and ambiguous than the usual western because the good guy, well, there’s a reason they call Harry “Dirty.” (This comes up several times in the film, the question of why he’s “Dirty” Harry, with a number of possible reasons thrown out. I think that final scene with the badge is the film’s only suggestion of the real answer.)

First off, I see it as an urban western, and loving westerns that may explain why I like it so much. Harry’s a loner, operating on his own (often to the exasperation of his superiors). He gets little help – some, but not a lot – and he’s after a really bad guy. So it’s framed like a moral tale, the way westerns are … but this leads us into the politics again. It is a moral tale but one a lot more subtle and ambiguous than the usual western because the good guy, well, there’s a reason they call Harry “Dirty.” (This comes up several times in the film, the question of why he’s “Dirty” Harry, with a number of possible reasons thrown out. I think that final scene with the badge is the film’s only suggestion of the real answer.)

Another aspect I like about the movie is how very, very seventies it looks. Of course there are the clothes, the hair, the cars … but I think even more so it’s the overall look of the film. With that look, today it would be called an indie film. Despite some restoration, it still feels gritty and grainy, even when it isn’t. Not only does the movie not look slick, it almost looks anti-slick, as if it’s trying to disassociate itself from Hollywood – a characteristic of a number of movies from that period, like Taxi Driver, for instance.

I was also struck by a nice difference between Dirty Harry and its progeny, more contemporary movies with heroes and really bad villains. Today, a character like Harry would be up against an almost superhuman bad guy. But in this movie, the character of Scorpio, while very bad, is almost something of a screw up. I’m thinking of one scene where he’s out to shoot another victim but gets spotted by the police in their helicopter. Scorpio is bad, he’s dangerous, he’s sick, but he’s not a brilliant criminal mind. He’s not nearly as clever as he would like to imagine himself, and nowhere near as clever as a character such as him would be in a contemporary movie. In other words, there’s a bit more realism to Harry and his bad guy. (And realism is one of the things movies of that period aspired to.)

Finally, I believe one of the reasons this movie is so satisfying is because it understands so well set up and payoff. Like the way good jokes work, with their structure and their rhythm, there are a number of scenes in Dirty Harry that deliver the same way (for example, the “Do you feel lucky, punk?” scenes).

An interesting comparison between Dirty Harry an one of its progeny is the recent revenge film, Man on Fire, with Denzel Washington in the lead role. Whereas in Harry, directing and cinematography are almost self-effacing, with most of the emphasis on story and performance, Man on Fire is very self-consciously directed and very obvious in its cinematography, almost the exact opposite of the Don Seigal film. And whereas Harry is consumed with his hatred for bad guys and indifferent to what he does to nail them (with the possible exception of the end with the badge), Denzel’s character in Man on Fire is almost morose with awareness of being lost to the dark side and, when he goes after the bad guys, is almost like a suicide bomber, willing to do whatever needs to be done and sacrificing himself willingly as a kind of redemption. (And Denzel’s bad guy is much more clever than the Scorpio killer.)

Despite being a film from 1971 and looking very much so, Dirty Harry still works and works brilliantly. It’s just a troubling with its ambiguous politics, and just as thrilling with its cop chasing a killer suspense. I loved it.

(Note: For some of Clint Eastwood’s views on Dirty Harry, have a look at the 1974 Playboy interview, Eastwood Talks Dirty Harry. Amongst other things, when the badge scene from the movie comes up and the reference to a similar scene in High Noon, Eastwood disagees with the comparison saying High Plains Drifter is much more along the lines of the Gary Cooper film.)

Movies seen (and not)

It’s felicitous, and perhaps there’s something in the way the planets are aligned, that the top ten list Raymond Benson is presenting on Britannica Blog is focused on 1968 since I seem to be taken up with movies from the late sixties/early seventies these days. Today he gave us his number ten, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, and I’m chagrined by the fact that I haven’t seen it. Of course, I was twelve when it came out and it’s entirely possible I saw it in later years on TV but, if so, I don’t recall it. However, the upside is that there is a reportedly fabulous movie waiting for me to see. So it’s high on my list of “to be viewed.”

Currently, I seem to be taken up with the Dirty Harry movies (the 1970’s). I’ve recently watched the first three (Dirty Harry, Magnum Force and The Enforcer) and soon will see the last two (Sudden Impact and The Dead Pool). On Saturday I watched Dirty Harry (1971) again and wrote a review about it, which I haven’t really highlighted because I’ve found I don’t entirely agree with what I wrote and plan to do a revision of it.

Currently, I seem to be taken up with the Dirty Harry movies (the 1970’s). I’ve recently watched the first three (Dirty Harry, Magnum Force and The Enforcer) and soon will see the last two (Sudden Impact and The Dead Pool). On Saturday I watched Dirty Harry (1971) again and wrote a review about it, which I haven’t really highlighted because I’ve found I don’t entirely agree with what I wrote and plan to do a revision of it.

Essentially, I consider it an urban western. After watching a number of the DVD features, I find I’m not alone in this opinion. Oddly, for what seems, on the surface, a pretty simple movie, Dirty Harry is a difficult film to get a handle on, and to a lesser extent so is the Dirty Harry series, because of the perceived politics of the film and the violence.

It should be mentioned that the first movie, Dirty Harry, is a classic (to use an over-used term). The other films in the series, while to varying degrees entertaining, are not in the same league at all. I think this is at least partly due to the fact that those movies, and the character of Harry, are somewhat muted in comparison. In the original, Harry is pretty darned focused and is motivated, simply, by hatred for bad guys and “the system.”

But I’ll leave all that to my revised review, when I get around to that revision.

(I wonder what Benson’s number 9 movie from 1968 will be?)

Another Clint Eastwood film – Blood Work

Last night I watched Clint Eastwood’s movie, Blood Work. I saw it, and wrote about it, back in 2002. I liked it then. Perhaps I liked it a little more this time. It really is a good movie. Here’s what I wrote back in 2002, with it’s asinine opening paragraph and some opinions I don’t necessarily agree with anymore. But, on the whole, in it’s essence, this is pretty bang on. And it goes like this:

Blood Work (2002)

I think Hollywood must be puzzled over what to make of Clint Eastwood. You almost get the feeling they allow him to make movies out of a sense of obligation – he represents an older style within a Hollywood dominated and obsessed by youth. It would be in just too much bad taste for even Hollywood to shut the door on him because he’s, well, old.

But what must be a real head-scratcher for them is the fact that he keeps making good movies. They’re just not today’s Hollywood movies. This, by the way, is one of the reasons they are so good, and come as such a relief.

Blood Work is another good Eastwood movie, though it’s not his best as it has some flaws.

The strength of the movie comes from its script. This is usually the case with Eastwood films of the last few years. He somehow finds strong stories then allows them to play out with little directorial interference. In other words, his direction is understated. It’s almost a hands-off approach. Thus, we get clean, well-framed shots edited in an unobtrusive way that still maintains the film’s pace.

The pace, by the way, is less frantic than the majority of current films. This is partly due to the style Eastwood has developed over the years, the fact that his influences are older (as he is), but also because he has focused so much on ensuring he has a strong story to tell. There is no sense that many films now have that the director lacks confidence in his story and feels the need to throw some razzle dazzle in to keep an audience’s attention.

This is not to say there aren’t some problems with Blood Work, the chief of which lies in the script I’ve been praising. The script has two key relationships within it – that of Eastwood and the character played by Wanda De Jesus, and Eastwood and the character played by of Jeff Daniels. It is in the latter relationship that the weakness lies, but it’s weakness is also because thematically the film’s focus is the former relationship (with de Jesus).

Warning: Spoiler

Broadly, the story is about a man who loses something of himself following a heart transplant operation. An FBI profiler, he receives the heart of a murder victim, the sister of Wanda de Jesus character. This character, de Jesus, has also suffered a loss – her sister. The movie is about how together they find and rebuild themselves, each helping the other.

The McGuffin for this comes from the serial killer who is the cause of both losses. The framework of the movie requires some mystery as to who this person is – Eastwood has to find and stop the killer. But it’s pretty clear who this person is fairly early in the film. This is partly due to the way the situation is set up, but also partly due to the casting. Given the casting, it’s hard to image that one of the film’s actors is playing such a seemingly inconsequential role. You can’t help thinking there must be more to it, and of course there is. You know, therefore, roughly how the plot will resolve.

This isn’t such a big problem, though. The only real problem is the suspicion you have that it is suppose to be a mystery. A better approach would have been to acknowledge how the film actually plays – that we know who the killer is and the film’s hook is seeing how Eastwood handles the mystery.

The reason this problem isn’t so large is because the heart of the movie (no pun intended) is not the mystery but the characters and how they find themselves again, individually and together.

Blood Work is thoroughly enjoyable on a number of levels, not the least of which is the relaxed, unrushed way it unfolds. It is a huge relief, especially during a season of blockbuster DVD releases like Minority Report, Lord of the Rings and Star Wars. It doesn’t rely on CGI, overwhelming landscapes, over-the-top camera work and so on. It relies on a story and strong acting performances, as well as unobstrusive camera work and direction. (It’s nice to see scenes that seem natural as opposed to tinted and with high contrast levels.)

Some years from now when the romance with technology and frenetic editing has passed and filmmakers turn again to a more naturalistic look, and a more minimalist approach, it will be to films like Eastwood’s that they will turn to for inspiration.

3 stars out of 4.