These days my movie viewing is restricted to what limited cable offers me. The selection is not great and that may be why the recent writings have been about relatively recent romantic comedies. It’s either those or movies about sweaty guys and things blowing up. So today, another rom-com … Continue reading

How one romantic comedy could have been fixed

It doesn’t seem right to call this a romantic comedy but that is how most would refer to it. Probably the most frustrating thing about it is that it could have been a good romantic comedy. It had the ingredients. It had the actors. So what went wrong? Continue reading

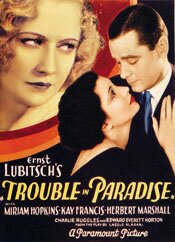

Ernst Lubitsch and his lustfully troubled Paradise

Without really planning too, I’ve found myself watching the movies of Ernst Lubitsch. A few nights ago it was The Shop Around the Corner. Last night it was Trouble in Paradise. I had seen both before, at least once each. What I find interesting is that the more I see them, the more I like them. The first time around you miss how well constructed they are because they evolve so seamlessly. So I definitely recommend seeing them at least twice.

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

Trouble in Paradise (1932)

One of the finest romantic comedies ever made, and one that in many ways created a template and set standards for later romantic comedies (while also looking ahead to the screwball comedies to come), is Ernst Lubitsch’s Trouble in Paradise, made in 1932.

With a single film, American cinema suddenly grew up. In many ways, it’s the most adult film Hollywood has ever made. (Not long after, production codes were put in place and much of what is in Trouble in Paradise would not have been allowed.)

Prior to Lubitsch’s first nonmusical American film, the sophisticated manner and style of this movie hadn’t been seen, not on this side of the Atlantic. Nor had this degree of elevated wit or sexual play.

Much is made of the “Lubitsch touch,” and there certainly is such a thing. While a bit hard to define precisely, it has a great deal to do with a European sensibility, one not informed by a Puritan cultural background. It has to do with wit and sophistication and adult romance.

Much is made of the “Lubitsch touch,” and there certainly is such a thing. While a bit hard to define precisely, it has a great deal to do with a European sensibility, one not informed by a Puritan cultural background. It has to do with wit and sophistication and adult romance.

Here, adult means playful, well-mannered and tinged by a degree of melancholy. Trouble in Paradise is a perfect example of this.

The movie is about two charming thieves, their love for one another, as well as their enjoyment of their craft. It’s about the playfulness between them, and the woman whom they choose as their mark.

Herbert Marshall is the thief Gaston Monescu. He charms his way into the life of Mariette Colet (Kay Francis) in order to steal her money. His love, the pickpocket Lily (Miriam Hopkins), is his accomplice.

But this is what Hitchcock would call the McGuffin. The movie is really about the triangle that develops as Gaston becomes romantically enchanted by Mariette just as she falls in love with him. All the while, Lily is still there and still loves Gaston, just as he still loves her.

But this is what Hitchcock would call the McGuffin. The movie is really about the triangle that develops as Gaston becomes romantically enchanted by Mariette just as she falls in love with him. All the while, Lily is still there and still loves Gaston, just as he still loves her.

Lubitsch’s direction is nothing less than wonderful here. One of the qualities that characterize his films, especially in Trouble in Paradise, is his refusal to be obvious about anything. He tells his story through indirection and implication, rarely being overt.

This is particularly true with the way he implies sexuality and its encounters without ever stating, much less showing, anything. It is part of the film’s playful wit and charm and adult quality. Equally adult is the absence of any salacious sense. There is no sense of “nudge-nudge, wink-wink” here.

Yet, essentially, the film is about lust, Gaston’s and Mariette’s.

As Peter Bogdanovich mentions in his introduction to the Criterion DVD of the film, it’s a wonder this was ever made in Hollywood, particularly when we see where we are today.

As Peter Bogdanovich mentions in his introduction to the Criterion DVD of the film, it’s a wonder this was ever made in Hollywood, particularly when we see where we are today.

While the troubled triangle of Gaston, Mariette and Lily plays out, the movie also gives us the ineffectual efforts of the Major (Charlie Ruggles) and Francois (Edward Everett Horton), two of Mariette’s luckless suitors. Their ineptness and pretensions provide a nice comedic counterpoint to the sophistication of Gaston.

Much of what Lubitsch does isn’t noticed on first viewing the movie. It is too seamless and fluid. The plot unfolds too effortlessly. It’s only on seeing a second or third or fourth time you see the small details he attends to and just how cleverly the movie is constructed.

In cinema terms, Ernst Lubitsch was a magician. Much of what he does is a kind of sleight of hand — verbal and visual. His movies, like Trouble in Paradise, are mature, charming and absolutely wonderful.

See:

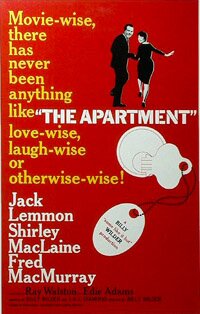

The Apartment and the melancholy Billy Wilder

While Billy Wilder movies are often spoken of in terms of romantic comedies (which many of them are – kind of), the thing that most strikes me about them is the melancholy that informs them.

More often than not his lead characters are lonely and sad. The stories that unfold are usually ones where that isolation is alleviated and happiness, to varying degrees, is found at the end – which generally is the way romantic comedies unfold.

But the humour in his films is often mitigated by the quality of sadness. They are often amusing, even funny, but not terribly so because there is a constant awareness of the human drama underpinning everything.

In The Apartment we get a good example of this. It’s a very good movie. It’s a funny movie – but not wildly funny.

Everything is flavoured by the quality of sadness which comes from who Wilder’s main characters are and their lonely situation.

Jack Lemmon plays C.C. (‘Bud’) Baxter, a bachelor who is trying to get ahead in a large corporation. For a year now, he has been lending his apartment to the company’s executives (his seniors in the corporation; men with pull who can help his career). They use it for their romantic trysts – extramarital ones.

Jack Lemmon plays C.C. (‘Bud’) Baxter, a bachelor who is trying to get ahead in a large corporation. For a year now, he has been lending his apartment to the company’s executives (his seniors in the corporation; men with pull who can help his career). They use it for their romantic trysts – extramarital ones.

Baxter has no life himself, not beyond his job. He lives alone, stays late in the office, and often spends his evenings killing time waiting till his apartment is free to come home to.

Shirley MacLaine is Fran Kubelik, an elevator operator in the building Bud works in. She is also single. Though seemingly above the sexual shenanigans of the office, it turns out she is (or has been) the mistress of the company’s head executive (Fred MacMurray).

Despite the questionable decisions they have made (Baxter to use his apartment as he does, Fran to be someone’s mistress), they are the only two decent people in the office. (Neither is comfortable with their morally compromised situations.) It’s interesting, and likely deliberate, that with the exception of Fran and Baxter the office has no genuine, decent people but those kinds of people do exist outside of it (such as Baxter’s neighbour, the doctor).

Despite the questionable decisions they have made (Baxter to use his apartment as he does, Fran to be someone’s mistress), they are the only two decent people in the office. (Neither is comfortable with their morally compromised situations.) It’s interesting, and likely deliberate, that with the exception of Fran and Baxter the office has no genuine, decent people but those kinds of people do exist outside of it (such as Baxter’s neighbour, the doctor).

The consequences of the compromises Baxter and Lemmon make are tragic, even severe, but not insurmountable.

Both are lonely and miserable and both acquire an acute awareness of this through their growing relationship, primarily as friends (at least at the start of the relationship).

Both are lonely and miserable and both acquire an acute awareness of this through their growing relationship, primarily as friends (at least at the start of the relationship).

They find one another and this is what they need in order to get out of their situations – the strength and support they find in one another.

The Apartment is very good movie with a similar romantic theme to the later film, Avanti! Lemmon, MacLaine and MacMurray all give great and convincing performances.

(Originally posted 2003)

Links:

- The Apartment on Amazon (Collector’s Edition)

How do you make movies about nice people?

Having been the really big little movie of a year or so ago, Juno (2007) hardly needs another review and so, other than to say I liked it a lot and consider it one of the better movies of the last few years, I’m not going to review it.

But I’d like to muse a while on something Juno does that I think is very difficult to do and very uncommon. It’s a movie about nice people. In fact, to the best of my recollection, everyone in the movie is a nice person. How do you make a movie about a nice guy (or gal)? And how do you make one where every character is a nice person?

Bad guy roles are often the ones actors (and directors) like to get a hold of: it’s much more interesting and, I suspect, easier to play. There’s more to work with because there is more to explore, or so it seems. Not to take anything away from Heath Ledger’s performance as The Joker in The Dark Knight, but there are more ways into and more avenues to examine in a character like that as opposed to, for example, Victor Navorkski (Tom Hanks) in The Terminal.

So I have a fascination with movies that feature “nice guys” – at least, those where I think the movies, and particularly the roles, work. For example and comparison, look at one of the nice guy roles in a movie like The Core (2003), Bruce Greenwood as Cmdr. Robert Iverson. It’s about as colourless and bland as you could imagine. Yet with few, if any, opportunities, Greenwood makes him one of the more interesting and compelling characters in the movie. No, it’s not a huge role – the character is a minor one.

Now look at the thankless role Bill Pullman has as President of the United States in Independence Day (1996). In that case, the role is equally bland, there is just as little to work with and what ends up on screen is bland. In both cases the “nice guy” is supposed to be interesting because he’s heroic – and that’s just about all. Yet Greenwood manages, somehow, to find some shading to make his character a bit more than cardboard.

In most movies, nice guy heroes are pretty one dimensional. What goes on around them is what engages, if it engages at all, and often what surrounds them and grabs us is the bad guy, or at least the troubled character. Heroes are often, in these cases, “troubled” – they have some character flaw because, well, they’re darned boring otherwise (see Bruce Willis as John McClane in Die Hard.

How, then, do movies like Juno or The Terminal manage to make good stories that feature nice people?

For one thing, they are romantic comedies. In those movies, while there may be a “bad guy” kind of character – a spouse, significant other, a boss etc. – the movie’s drama isn’t the conflict with “the bad guy” but situational, between two nice people. We want the conflict resolved so the two of them can get together.

But it seems to me that when a movie that features nice people works best it is almost always ensemble work. Yes, one or two characters are the focus, but the movie is hugely dependent on the characters surrounding them – almost always other nice people. (Think of those classic Hollywood movies like The Philadelphia Story or My Man Godfrey or Sabrina.)

As much as Ellen Page as Juno is the focus of Juno, and as good as her performance is, the movie is nothing without the ensemble – Paulie, Juno’s parents, the adopting couple, Juno’s friends. And they all share in common, with Juno, “niceness” and (for lack of a better word), quirkiness.

While we refer to it as quirkiness, however, is it really? I suppose so but, in the movies that work, it’s also character – there are reasons for the quirky behaviour. I can’t imagine anyone, anywhere not having distinct characteristics without being a blank slate.

Everyone we know has characteristics like this. Usually, the closer we are to someone – a friend, a family member – the more aware we are of their unique characteristics. It’s often what we love about them (and what we find annoying, at the same time). In movies, however, they are sometimes emphasized, or at least focused upon, because they lend themselves to humour and more importantly to character.

In a movie like The Station Agent (2003), it’s a small ensemble – just three, really. But that’s what makes the movie work – three nice people and each distinguished by their unique characteristics.

In a certain sense, you could say the successful portrayal of niceness is always (as far as I know) communal. While there are characters that are the film’s focus, it’s the community that supports them and the community – the ensemble – we’re drawn to, and this communal aspect is something romantic comedies do very, very well.

And it’s all so nice.