To be honest, I’ve never been a big Robert Altman fan, though increasingly I’m finding his movies more appealing. I think his approach creates the sense in me that I’m listening to a slow-talker and I want to interrupt and say, “Move it along; get to the point.” There’s an improvisational feel to character interaction and part of me want’s it more closely scripted and edited.

In The Long Goodbye this comes across partly because Altman gives his actors more responsibility to actually act, as he does with Elliott Gould here, and partly because the camera is constantly moving, as if you as a viewer are watching and trying to find a better vantage point. Some shots are through windows; some are even reflections in windows.

It’s intriguing, yet for me a bit irksome — but that’s just a personal, subjective thing. And what is odd about it is that I like this movie nonetheless.

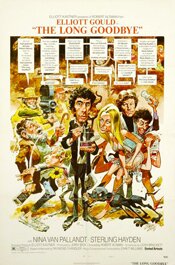

The Long Goodbye (1973)

The Long Goodbye (1973)

Directed by Robert Altman

Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye is a bit like a fast food hamburger. It has beef in it but also has so many other things, and it has been altered to such a degree, that while it resembles a hamburger, it ain’t no hamburger.

In the same way, Altman’s movie is Raymond Chandler’s book, and resembles a film version of that book, but it ain’t Chandler’s book.

But then, you wouldn’t expect Altman to make a movie utterly faithful to its source.

Altman’s movie begins with the question, “What would happen if Marlowe, a character of the 40s and 50s, were to wake up and find himself in the early 70s?” In an interview, he says they referred to it as “Rip Van Marlowe” during the making of the movie. This idea dictates how the movie plays out.

Chandler’s Marlowe began in 1939 with The Big Sleep. His book The Long Goodbye was published in 1953. That is exactly twenty years before Altman’s The Long Goodbye.

Chandler’s Marlowe had been in about six books prior to the 1953 book. In The Long Goodbye, his Marlowe is older and mellower. The novel is a bit more reflective and, in my opinion, weighty. There is less emphasis on the tough guy posturing of the early books; he comes across as a more mature character. In some ways, there is a sense of alternating melancholy and apathy in him.

This may be what suggests the “Rip Van Marlowe” possibility to screenwriter Leigh Brackett and director Altman, or at least what makes this book a possible vehicle for working out that theme. However, there is more to the theme than just the “what if” aspect of a man from 1953 waking up in 1973. One thing that has changed for Marlowe is how people view friendship. The world has a different sense of ethics and morality and it isn’t in sync with his.

The movie opens with Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) literally waking up. The first half of the movie, particularly the first twenty minutes or so, give us such a slovenly, disconnected and half-asleep Marlowe that, the portrayal being so effective, he is incredibly annoying. He speaks under his breath, muttering to himself more than anyone else, even when responding to others around him. He’s almost completely unengaged with his world.

He shows no animation at all until his friend, Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) shows up at his door. This is where the story’s engine turns over and it gets underway as Terry asks Marlowe to take him to Mexico.

The story makes some major turns from the Chandler book, some for the purposes of condensation and some … Perhaps because they didn’t want to make a movie faithful to its source but one that stood on its own legs as unique.

Having re-read the book recently (which is probably why I keep referring back to it), and it being my favourite of the Chandler novels, I can’t say I like the deviations. I found the book had more meaning for me than the movie largely because of those things that have been changed, though I do like the movie on its own merits.

But the book’s ending is much more effective and moving, I think. The movie is very direct – you can’t miss its point. In a way, it’s like Altman believes he has to be direct because people in 1973 are as much asleep as Marlowe was. His conclusion is like a bucket of cold water in the face.

The “asleep” idea recurs through the movie. It’s not just Marlowe who is somnambulant. His neighbours, the young women with their yoga and exercise, appear to be lost in their own world of new age exercise and spirituality. Roger Wade (Sterling Haydon) is lost in his alcohol and self-pity. Everyone is self-absorbed and inward looking and Marlowe is the one person who “wakened” to this contagion of social sleepwalking.

Marlowe “wakes up” because something has wakened him: the death of his friend Terry Lennox. He remains true to his friend, though for all intents and purposes it’s meaningless, isn’t it? (Terry is dead, after all.) Yet Marlowe won’t believe the murder and suicide that are being attributed to his friend.

No one else in the movie is true to anyone or anything. Even Marlowe’s cat abandons him when its favourite food is no longer there. Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell) speaks of how much he loves his girlfriend then strike her horribly for no reason. Roger Wade hits his wife when he is drunk.

Throughout the movie, as Marlowe makes his way, he sees a world of self-interest and no loyalty, making him an anachronism. When asked why he would try to clear the name of Terry Lennox, he hears variations of, “What’s it matter? He’s dead.”

The ending aside, this is probably the greatest deviation from the novel. In the book, respect and loyalty keep appearing – Marlowe is hired for his; the gangsters in the book (unlike the Marty Augustine character) respect Marlowe for his loyalty. Even some of the cops do. He is sought out and hired because it’s reported in the newspapers that he was picked up by the police for questioning and wouldn’t talk.

So the difference in the endings becomes a bit curious. Is it simply a more overt, can’t-miss-that meaning concerning betrayal of a friendship or is it also suggesting that Marlowe, too, is becoming part of that amoral culture of self-centeredness?

I’m not really sure. But I do know this is a curious movie Robert Altman has given us.