(A repost from November, 2010.)

A friend of mine went to visit some friends in Edmonton a few months ago. When she returned, I asked her what she had done. “Nothing,” she said. Continue reading

(A repost from November, 2010.)

A friend of mine went to visit some friends in Edmonton a few months ago. When she returned, I asked her what she had done. “Nothing,” she said. Continue reading

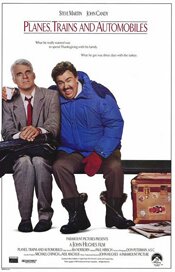

I’ve been prattling about comfort movies recently but so far have suggested only one example from the list I’m compiling. But tomorrow, Thursday, is Thanksgiving in the United States — which may go back as far as 1565, finding its start in Florida. I say “may.” I’m not saying it is so.

Regardless, that brings me to one of my favourite “comfort movies” of all, Planes, Trains and Automobiles, a movie that is all about Thanksgiving.

Directed by John Hughes

Directed by John Hughes

Planes, Trains and Automobiles is an absolute gem of a movie. One of the reasons it succeeds so well is because it is so simple and maintains its focus throughout.

Steve Martin (Neal) is heading home to Chicago for Thanksgiving. So is John Candy (Del). They are travellers with personalities at opposite ends: Neal is a prim and proper, an anal businessman, while Del is a talkative, somewhat crass low-rent guy who sells shower curtain rings. Circumstances, increasingly ludicrous yet believable, keep throwing them together. Martin’s character feels nothing but irritation about his situation and with Candy’s character while Candy’s Del is oblivious – he just goes with the flow. Together, they take planes, trains, cars, trucks and so on as they try to get home.

It’s a variation of the buddy, road-movie of film. But I think it shows why these kinds of movies are so popular when they’re well done. It is all about the characters and their relationship. In this case, Steve Martin and John Candy are a perfect pairing. I’ve always liked Martin best when he plays more of a straight character. In this film, he plays straight though this doesn’t mean he’s not comedic. On the contrary, he is more comedic because of this. Everything happens to him and his reactions are priceless.

Candy, on the other hand, has never been more lovably obnoxious. He’s the boob, the stooge. Always well-intentioned but almost everything he does causes disaster for Martin’s Neal. It’s very much a Laurel and Hardy or Martin and Lewis kind of combination that they play. A lot of the humour is slapstick – visual – and it works well. While many comedies are amusing, I find I don’t often laugh as I watch them, though I may smile. In this movie, I laughed. And that is the litmus test for comedy.

Candy, on the other hand, has never been more lovably obnoxious. He’s the boob, the stooge. Always well-intentioned but almost everything he does causes disaster for Martin’s Neal. It’s very much a Laurel and Hardy or Martin and Lewis kind of combination that they play. A lot of the humour is slapstick – visual – and it works well. While many comedies are amusing, I find I don’t often laugh as I watch them, though I may smile. In this movie, I laughed. And that is the litmus test for comedy.

The film, however, doesn’t work just because of its comedy. And the comedy doesn’t work in a vacuum. The characters created by writer-director John Hughes’ script, and brought to life by Martin and Candy, are what allow everything to play out successfully. It’s in the developing relationship, and the degree of depth the actors give their characters, that guides the movie forward.

The movie isn’t just about getting laughs; it has a theme which is the value of home and relationships. Thematically, it’s similar to It’s A Wonderful Life. It’s not particularly profound; it’s rather simple. But again, this simplicity is part of what allows the film to work and also part of its appeal. It’s accessible and understandable to pretty much everyone. The key in making a movie such as this is avoiding a saccharine quality. This movie, while it may have a wisp of that, doesn’t succumb and this gives it credibility. The humour, too, takes the edge off any hint of sappiness.

I think, too, there’s something worth an essay or two in the fact that movies like Planes, Trains and Automobiles (and many Capra films like It’s A Wonderful Life) can be and are watched over and over again.

I think, too, there’s something worth an essay or two in the fact that movies like Planes, Trains and Automobiles (and many Capra films like It’s A Wonderful Life) can be and are watched over and over again.

Why is something so simple so compelling? Why do other, more apparently profound films, hard to view more than once without becoming bored, while films like this can be seen again and again? As with children when they want to hear the same story over and over, certain stories, certain themes, address something we need to have repeated for one reason or another. I think it probably has something to do with truth – not the truth of tangible reality, but some truth or truths about us, people, and our relationships with one another.

If you haven’t seen Planes, Trains and Automobiles, or if it has been a while since you’ve seen it, this one is highly recommended. It’s what a comedy should be – funny. In fact the only reservation I have about the movie, the only thing I could find fault with, is the music. It sets the film far too firmly in the 1980’s. If the music were removed, the film is timeless.

But don’t worry – the music isn’t bad. Just anachronistic. And it doesn’t interfere with the enjoyment of the film. (But let me add – I loved the carousel sounding rendition of the Red River Valley song.)

On Amazon:

A friend of mine went to visit some friends in Edmonton a few months ago. When she returned, I asked her what she had done. “Nothing,” she said.

“Did you go anywhere?”

“Nope.”

“Did you at least go to that restaurant I told you about?”

“No; there wasn’t time.”

She had been there for over a week. Yet all she had done was spend time with her friends.

That’s what some comfort movies are.

Many years ago when the marathon-like M*A*S*H was finally ending its time on television, someone made the observation that few people had watched it because they were eager to see the next episode. They weren’t wondering what would happen next. They were watching simply because they wanted to spend time with the characters they had come to know so well.

That is what some comfort movies do. Many of the John Wayne movies are like this. They may have drama or comedy but many people watch them simply to spend time with their idea of John Wayne and the characters associated with him.

This particularly comes across in his later movies, like Hatari! or Donovan’s Reef, or even an earlier movie like The Quiet Man. Their merits as films aside, people watch to see the Duke and the actors/characters associated with him, like Maureen O’Hara. There is a sense of knowing them, of a personal relationship, though we know that couldn’t possibly be true – we’ve never even met them! Yet we feel that way.

So it strikes me that a characteristic of comfort movies is familiarity. We revisit certain movies in the same way we revisit certain friends and family. Familiarity. We enjoy spending time with them. This is why they are comfort movies.

So it strikes me that a characteristic of comfort movies is familiarity. We revisit certain movies in the same way we revisit certain friends and family. Familiarity. We enjoy spending time with them. This is why they are comfort movies.

Although it’s not the movie I’d like to start off with (it’s a bit misleading as far as what I consider a comfort movie to be), my favourite movie as far as this category goes is Father Goose.

Gasp! Am I nuts? Possibly. But for me this movie is as comfortable as old slippers. And that may be a good analogy because this movie is probably just as fashionable. Besides, it stars the always familiar Cary Grant, whom many simply like to watch. In anything.

I often refer to certain films as comfort movies. I think I started using this term because my lingering wannabe cinema buff always felt a bit embarrassed at liking some movies. The term is a variation on the phrase “guilty pleasure” but a bit more specific, though I may not be able to articulate well what I mean by it.

In some ways, it’s best defined by what it is not. A comfort movie isn’t challenging. It seldom has lofty artistic aspirations; usually, it simply wants to entertain. Comfort movies, for the most part, aren’t dark, though they may have dark aspects to them, to varying degrees. (After all, there is no drama without some dark element.)

Possibly the best known example of a comfort movie (though it isn’t that for me) is It’s A Wonderful Life. People watch this movie over and over. It’s hard to miss, mind you, because it’s on TV repeatedly in the holiday season. It’s a movie with darkness, quite a bit of it actually, yet its big Norman Rockwell-like finish makes us feel so good we watch it again next year.

Off the top of my head, I can’t think of a single comfort movie that doesn’t have a happy ending, though sometimes it’s a bit equivocated. A happy ending may be a defining characteristic of the comfort movie.

By contrast, there is a movie like The Godfather. It may be my favourite movie of all time (it’s not) and it may be my standard of what a film should be and do, but it’s not a comfort movie. You don’t watch The Godfather because it makes you feel good; not in the sense I mean. You don’t remember it for a happy ending or sense of elation.

I’ve decided I’m going to make a personal list of comfort movies. This may help me get closer to a more clear definition of what I intuitively know is a comfort movie.

I’m going to list twenty of them. This assumes that I can come up with twenty. I think I can, so very shortly I’m going to start putting them up on Piddleville.

(After reading this over, I think I’ll probably disagree with it as I start my making my list. I was just going over some of the movies I would put on it and realized two things: 1) quite a few of them are at odds with my attempted definition, and 2) a change in cinema and sensibilities in about the 1970’s redefined what I think of as a comfort movie. So as usual I’m full of hooey.)

Also see: