No snide comment is implied by “Errol Flynn … gains some gravity,” though by the time this movie was made the older Flynn had put on a few pounds. Rather, his performance has a bit of weight that wasn’t there in the younger Flynn’s roles. You can see it in this movie, The Master of Ballantrae, though I don’t think anyone would rate the movie itself terribly high.

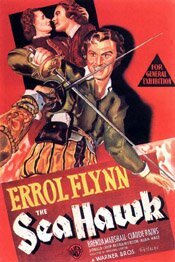

The impish Errol Flynn in a swashbuckler

A few years ago I bought a fistful of Errol Flynn movies that were in one of those many Warner Brothers collections. I had only vague memories of Flynn movies but was curious having seen The Adventures of Robin Hood and, a few years earlier, having read his autobiography, My Wicked, Wicked Ways (recommended, by the way — it is so much fun to read).

Among the movies in the collection was the one I scribbled about below, The Sea Hawk. Interestingly, just as Robin Hood was directed (in part) by Michael Curtiz, he also directs this movie. He seems to have been aware of what Flynn brought to these movies and was very good at getting it.

The Sea Hawk (1940)

The Sea Hawk (1940)

Directed by Michael Curtiz

I’m halfway through Errol Flynn: The Signature Collection and I think I’ve hit the real gem of the lot. (Not that the others aren’t good too.) It’s The Sea Hawk and it really does put the “swash” in swashbuckler.

It’s absolutely brilliant and in a number of respects. I can’t help comparing it to The Adventures of Robin Hood. It has much of the same feel while at the same time has a little something different.

For one thing, both films capture a sense of fun and exuberance. Both also manage to be rousing costume adventures without any sense of self-consciousness though The Sea Hawk differs slightly in that Errol Flynn plays the British pirate Captain Geoffrey Thorpe with a kind of very contained impishness.

His captain is apparently quite serious, patriotic and heroic, yet every now and then he seems to be restraining a smile or grin.

As someone in the special feature on the DVD says (The Sea Hawk: Flynn in Action), it’s almost as if Flynn is asking the audience, “Are you really buying this?”

But in these Flynn movies this kind of feeling is not one of mocking the audience but of having fun with them. Flynn seems to play his swashbuckling roles the way the early Springsteen played concerts – the more fun the audience had, the more fun he had and together they create a kind of synergistic relationship.

Another fascinating way in which The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Sea Hawk compare is in their look. Where Robin Hood is an incredibly exuberant display of colour, The Sea Hawk is nothing less than a magnificent example of black and white. (Although I could have done without the Panama scenes done in sepia.)

The sea battles between the ships are fabulous.

We know from recent films like Master and Commander that great sea battles can be done in colour but I’ll take The Sea Hawk’s scenes anytime. (It’s also incredible to think these were done on sets.)

There is also a great sword fight (as there must be to conclude an Errol Flynn swashbuckler) where, again, the black and white scenes with their use of light and shadow are exceptional. I loved the great shadows on the walls during the struggle.

The Sea Hawk is about as close to the quintessential swashbuckler as you can get. It has Errol Flynn, the man who pretty much defines the hero of such movies.

It has the great set pieces like the sea battles and the swordfights. And it has the music that has influenced the sound of almost all heroic adventures.

Credit for the music goes to Erich Wolfgang Korngold. His score (which is apparently not just rousing but quite clever as it uses, in part, themes from the earlier The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex but in a reworked form), is operatic which, if you think about it, is really what such romantic adventures require.

I really didn’t know a great deal about The Sea Hawk before watching it. And to be honest, I wasn’t expecting a great deal. I basically put it in the DVD player because I wanted to watch something and I hadn’t seen this one yet.

As often happens, when I was least expecting it, I encountered a wonderful movie. Highly recommended.

(The Sea Hawk also aired last night on TCM. I missed it but I may watch my copy again tonight. The above was written roughly about April 2005.)

Robin and Marian: ‘Where did the day go?’

Here is the Robin Hood we don’t get to see enough. He’s old. As Marian notes,“You had the sweetest body when you left. Hard, and not a mark. And you were mine. When you left I thought I’d die. I even tried … No more scars, Robin. It’s too much to lose you twice.”

As movies go, this one is very odd. It is so flawed and yet so good.

Robin and Marian (1976)

Directed by Richard Lester

“’The day is ours, Robin,’ you used to say, and then it was tomorrow. But where did the day go?”

This 1976 take on the Robin Hood story, Robin and Marion, isn’t terribly interested in the standard “steal from the rich; give to the poor” tale. It’s interested in the pointlessness and vanity of violence. This Robin Hood (Sean Connery) may be a hero but he’s one with a tragic flaw: his pride.

The movie is also a love story. It’s about a love wasted because of that pride.

It’s directed by Richard Lester and fortunately suffers less from his chaotic excesses than other films he made, though they are there.

You know from the opening scenes that this story isn’t going to be about great battles and heroism.

It opens with two knights digging something up. Each knight is weighted down by heavy, shielding clothing and each has a helmet on. The helmets are like huge buckets on the knights’ heads and as they dig their heads bang together. It’s not a heroic image; it is comic. It’s satirical and slapstick.

This movie is about a Robin Hood twenty or more years down the road from the days of exploits in Sherwood Forest. It’s the latter half of the Robin Hood legend, the one not often told (at least in films).

Robin and many of his men have been off to the Holy Land and the Crusades fighting for King Richard the Lionheart (Richard Harris) who happens to be vain, violent and probably psychopathic (as far as the film sees him). Robin follows simply because “… he’s my King.” He’s actually sickened by Richard’s ways.

Richard finally dies so a weary Robin and Little John (Nicol Williamson) decide to go home to Sherwood Forest.

They do but while on the surface much is still the same, much is very different. It isn’t the world they left. Like themselves, people are older. The Sheriff of Nottingham (Robert Shaw) is no longer the angry, frustrated man we remember; he’s reflective, even at peace in a way. In some ways, he seems more dangerous because he has learned patience.

When Robin comes across some of his old friends like Will and Friar Tuck, they are older and simply struggling to survive in Sherwood Forest as peasants. And then there is Marian (Audrey Hepburn).

Until she is introduced, Robin and Marian is an average film that satirizes and mocks violence and heroism. Once we meet Marian, the movie elevates itself into something more.

Years earlier when he left to join Richard, Robin left without a word. Robin gave himself to his king. Marian, despairing and after one suicide attempt, joined a convent and gave herself to God. Robin, with Richard dead, is free to come back to Marian and he does, thinking he can go back to how things were with only some minor patching up to do.

But Marian won’t have it. She does God’s work now; he’s her king.

The real story of Robin and Marian is how the relationship between Robin and Marian plays out.

Many reviews of this movie use the word “weird” and they are right to do so. It is weird. It’s a movie that isn’t quite sure what it wants to do. Or, rather, it does know but wants to do too many things and ends up muddled because of this.

On one hand, it is satirical and uses visual, even slapstick comedy. On the other, it is romantic in its love story. There is a mixing of tones and it puts the movie a bit off kilter. Both kinds of movie work; both tones work. They just don’t sit well with each other.

There is, however, a tone of romantic weariness that weaves its way through the movie from Robin to Richard to the Sheriff to Marian and this acts as a kind of anchor. The ship does get tossed from side to side quite a bit but it manages to stay in place.

There are really two Robins in this movie. The first one we meet is more or less a weary old man. He has lost the verve of youth and is tired of the pointlessness of fighting.

Once Richard’s death frees him and he returns to Sherwood Forest the other Robin emerges and this one is the real Robin Hood: a man who is still a boy.

This is where tragedy of the Robin and Marian love story is rooted. Robin has never grown up; Marian has.

What develops is a love story for grown ups. In its resolution, we find the last part of the Robin Hood legend, tweaked a little (in a good way) and a final scene that is touched with nostalgia and sentiment but not to the film’s detriment. It is simply beautiful.

This film definitely has its flaws but on the whole it is wonderful. The story is compelling and the performances of Sean Connery and Audrey Hepburn are exquisite. (This is my favourite Sean Connery performance.)

There is also Richard Harris as Richard the Lionheart. He’s wonderful though you can’t help wishing there had been more of him in the movie. Robert Shaw also gives a great interpretation of the Sheriff of Nottingham, a mix of world weariness, patience and guile.

There is battle scene near the film’s end that captures the core of the Robin Hood character in this version. It is between Robin and the Sheriff. Unlike what we usually see, the swashbuckling swordplay we might anticipate, is plodding and devoid of anything heroic. It is two boys, now old men, fighting what is really a schoolyard battle. They can barely lift their swords, much less wield them.

The Sheriff’s men watch, as do Robin’s. Everyone hopes to see their man win. But very quickly the various people watching begin to look on with sad, even horrified expressions. It is so clearly foolish. Even the Sheriff, as their battle nears its finish, fights with a tired, horrified expression. Robin won’t stop. The boy has to win.

When the fight ends, though seriously wounded Robin is invigorated and enthused. He’s alone in this though.

As far as Robin Hood movies go, Robin and Marian is right up there with 1938’s The Adventures of Robin Hood. In fact, they make for a good pairing as they complement one another as well as contrast with each other. You could say Connery’s Robin is Flynn’s twenty years on.

Links:

- Film Club: “The years they whittle at you”

- The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938)

My Wicked, Wicked Ways – review

The Autobiography of Errol Flynn (1959)

by Errol Flynn

I just finished reading, and thoroughly enjoyed, My Wicked, Wicked Ways: The Autobiography of Errol Flynn, originally published somewhere around 1959, available now through Cooper Square Press (part of Taylor Trade Publishing group).

Heavens, what a helluva good read. Is anything he says true? Well, maybe. Probably, at least some of it. But that’s not really the point, not for me.

It reads as if it’s the transcript of a recording of a great raconteur, a teller of tall-tales whose favourite tale is his own life. You get the sense of a man who is totally self-absorbed but, somehow, has such a winning personality you love him for it.

I originally picked up the book because I was interested in finding a unique character I might make use of in a story, a model for a supporting player. I had a vague notion that Errol Flynn might have some of the qualities I was looking for.

Well, geez … did I ever get my money’s worth in Flynn. It’s not simply a matter of a long, episodic tale of the picaresque variety, but also one of style. The words, syntax … everything that goes into creating a “voice” in writing, is here.

It’s the breezy voice of a kid who never grew up. In its conclusion, it’s also the voice of a kid who doesn’t quite understand how or why his life has gone the way it has.

For me, the incidents are less important than the personality that comes across (although the incidents are quite remarkable). Together, personality and incidents, it makes for an incredibly entertaining book.

The breezy tone of the adventures carries through for roughly the first two thirds of the book. The fantastic, tall-tale quality is richest as Flynn recounts his early life and his various adventures as he travelled the world, especially Tasmania, Australia and the south seas.

His accounts of his Hollywood life are equally entertaining while also being salacious and gossipy. The raconteur quality comes forth through what the book relates and how Flynn relates it.

Although the book overall is chronological, he bounces back and forth in time. This almost mimicks on the page the way someone tells a story orally as one thought prompts another.

Sometimes the jumps in time and subject are almost non-sequiters. Yet it never seems excessive or sloppy, simply stylisticly casual.

As the book winds down you get the sense Flynn is winding down. It’s almost as if he becomes disinterested. There’s a melancholy quality to the book as he becomes increasingly reflective.

While Flynn’s most winning quality seems to be a boyish charm, as the book progresses the negative side of that charm is immaturity. It’s this that seems to catch up to Flynn in the end.

Finally, the man at the end of the book comes across as one who is close to but not yet quite grasping the meaning of his life (pompous as that may sound). Or, to put it another way, time seems to catch up to Flynn. Age. The image we end up with is of a somewhat faded Hollywood star, alone at his beautiful Jamaican home, not entirely sure what remains of his life or what to do with what remains.

As the Wikipedia entry on Errol Flynn says, “By the mid 1950s, Flynn was something of a self-parody: heavy alcohol abuse left him noticeably bloated in his last years.” He died of heart failure in Vancouver a short time before this book came out.

Knowing something of the final years of Flynn’s life amplifies the melancholy of the book’s conclusion for the reader and makes its final line resonate in a sad way.

However, while this may be how it winds down it is certainly not the tone of the majority of the book. It is flush with a sense of fun and adventure and humour.

Flynn is a character, in the truest sense. He’s marvellous and if I had known him, I don’t think I would have trusted him any further than I could throw him.

(By the way, it sounds as if the writing of My Wicked, Wicked Ways was a great story too, or so the book’s introduction suggests. As another aside, Flynn originally wanted to call the book, In Like Me, as a play on the popular phrase, “In like Flynn,” a line that came about due to one of the episodes in his life.)

Originally posted in 2005 (or earlier).

My Wicked, Wicked Ways:

– Amazon.com

– Amazon.ca