Among the many fascinating and, in this case, amazing things about The Maltese Falcon is that it was the first film for Sydney Greenstreet who was 62 years old at the time. Can you imagine any actor today getting a role, much less starting a career at 62?

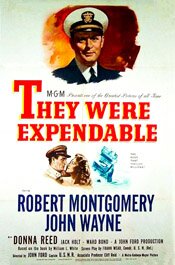

John Ford, John Wayne and Expendable

Sometimes the release dates of movies can be significant. Get it wrong and you’re all in a muddle, as I was when I watched They Were Expendable.

The movie itself isn’t anything I would say you should rush out to see unless you’re a really big John Ford and/or John Wayne fan. The tone of it is curious, however, given the kind of movie it is and what it is about. Some movies are intriguing despite not being great films and that is the case with this one.

They Were Expendable (1945)

They Were Expendable (1945)

Directed by John Ford

I was very confused when I watched the war movie They Were Expendable because I thought it was from 1941. It turns out that is when the movie is set as it opens. My confusion evaporated, however, when I realized it was from 1945, though it is still an unusual movie that John Ford gives us.

Believe me, with this movie the year really matters – especially if you confuse it with four years earlier.

This movie was released in December of 1945. In World War II, Japan formally surrendered in September of 1945.

The movie is somber recounting of the early days of the war for the U.S., beginning with the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941.

Made with the approval and assistance of the U.S. Navy, Army and Coast Guard, it shows us the U.S. getting its behind kicked by the Japanese – starting in Pearl Harbor and continuing through the Philippines.

Audiences at the time of the film’s release, however, would be fully and completely aware of the end result of it all – victory in the Pacific; Japan’s surrender.

The reason John Ford shows us all the bad news from the war’s early days is because he’s telling the story of the PT boats – how their role in the war came about (they weren’t highly regarded originally), how they won respect and the sacrifices made by the crews that worked them. (The tagline was, “A tribute to those who did so much… with so little!”) However, the main character is really the boat itself.

The movie is a solemn tribute and sober homage but also full of patriotism which, appropriate to the period of its release, may strike a current day viewer as a bit much.

There are good action scenes in the movie as well as some interesting, almost noir-ish lighting in others. The movie itself appears to be in poor shape, at least on the DVD copy I have. I don’t know if any restorative work went into it but it doesn’t appear so given the scratches in a number of scenes. I’m a bit surprised it comes to use from Warner Brothers. It may have something to do with the lack of good original film materials. I don’t know.

Overall, I can’t say this is a great movie. It’s a curious one, however. It’s worth seeing at least once, especially if you’re a fan of either John Ford or John Wayne. Just keep in mind this movie should probably be viewed as a propaganda work.

And maybe that is what makes it peculiar. It’s quite a bit of “Rah, rah!” about PT boats but seems to also want to be a solid drama and thus it acquires a bipolar quality.

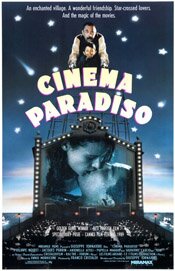

The strange love of movies – Cinema Paradiso

I last watched Cinema Paradiso about ten years ago. I’ve been meaning to watch it again for a long time but two things have held me back: the length (almost three hours — I don’t ever seem to have the time) and what I fear is a problem with my DVD copy. I hate the idea of getting halfway into a movie then finding a problem prevents me from seeing the rest.

But maybe this weekend I’ll overcome these hesitations. I really do want to see this again. For now, my impressions from when I saw it back around 2003 …

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Directed by Giuseppe Tornatore

My memory is poor, so I really don’t recall the original, theatrical version of Cinema Paradiso. Whether or not the longer version I have (the 2003 DVD release) is better, I’ve no idea. It adds 51 minutes to the film – a 174 minute movie compared to the theatrical release at 123.

This version of Cinema Paradiso is broken into three parts – the main character Salvatore as a child, a young man, and finally as an older man (middle-aged). It begins with a kind of prologue of Salvatore as the older man.

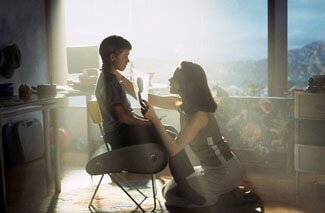

The beautiful opening shot is almost still, like a photograph. Slowly the camera pulls back as the opening credits roll. As we pull back, the image we have is truly a filmmaker’s image: it’s very deliberately staged and framed, and I think we’re supposed to be aware of this. It is still, as if frozen, somewhat like the memories of the character Salvatore.

As the camera continues back, we become aware that we’re looking through a window. Slowly retreating, at one moment it almost looks like a film screen.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

The current reality of this beginning (following the opening shot) establishes the kind of life Salvatore is living as a well-known filmmaker. It shows us a man avoiding his past. It gives us a man disconnected from his personal history and disconnected generally with the humanity around him. He’s isolated, and has chosen to be so.

The beginning also is what leads us into the story as it flashbacks to his life as a child, the film’s first section (following its prologue). It’s significant that we get into his childhood this way because it determines what we see and how we see it: it’s through the older Salvatore’s memory. It’s therefore not necessarily true in an objective sense.

This first part, Salvatore as a child (his memory of it), is generally brightly lit. It’s very open and spacious (compare the town square at the beginning of the film to the car-packed square at the end). In fact, everything here is open except for one thing: Alfredo’s little room in the Cinema Paradiso.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Like an image on film limited by the frames, his world is constrained by the walls of his projection room. But as the movie’s opening has shown us, and as demonstrated in Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, there is a world beyond the image’s frame (Tori’s mother in the movie’s opening). However much they may delight, or how real they may seem, movie’s are not everything. There is a world beyond them.

In the second part of the movie, Salvatore begins to become like Alfredo, at least this is a choice he is presented with. He takes over the projection booth. But he does have a choice and this is what the second part concerns.

While isolated in the projection booth, he also has a foot in the more tactile and chaotic world of the audience. This is through his relationship with the young woman Elena. In this part of the film, director Guiseppe Tornatore introduces a sexual element – in the films seen in the Cinema Paradiso, in the behavior of the boys of Salvatore’s age, and in Salvatore’s relationship with Elena, though this latter is more romantic in its treatment than sexual.

But the purpose of the sexuality is its relationship to romance and personal connections. It is something that pulls Salvatore away from the isolated world of films into the community of the audience, the town.

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

Salvatore’s relationship with Elena no longer a possibility, he now leaves the town (the audience). Alfredo not only supports this decision, he prompts it. He tells Salvatore, “You have to go away for a long time, many years, before you can come back and find your people.”

It’s ironic that Alfredo says this as he has never gone away, at least not physically. It could, however, be argued he has left emotionally and spiritually and has yet to return.

This leads to the film’s third part, the movie’s “now.” The older Salvatore finally returns to the town of Giancaldo. He returns for Alfredo’s funeral (who, in a sense, is finally “going away”). For Salvatore, the return is a series of revelations. As he says himself, he has been afraid to return.

One of his biggest discoveries is of Alfredo’s manipulations to keep Salvatore and Elena apart. She did not betray Salvatore, nor he her. It was Alfredo. His reasons were to force Salvatore out to his career as an artist, a famous filmmaker.

The other revelation is the film’s conclusion where Salvatore sits alone in the theatre watching Alfredo’s final gift, a reel of film. It is all the kisses and other intimate moments of human relationships the priest had removed from the movies. It is as if Alfredo is trying to return the part of life he had removed from Alfredo.

In contrast to the film’s beginning, this final section is visually darker and cramped. It is the real part of the film, as opposed to the remembered.

In this final part, we also see the destruction of the theatre, the Cinema Paradiso. While not the destruction of movies, it seems it’s the destruction of the tyranny of fantasy. While painful, it frees Salvatore from the confines imposed by images. It frees him of the prison art imposes and allows him back into life. We see a shot of young people laughing with a youthful sense of fun as they see the destruction of the building. It’s as if the present is clearing away the past so it can live.

The film appears to have two meanings, or at least two intents. In part, it is a loving homage to cinema and what it gives us. At the same time, it is also about the tyranny of art, at least for the artist. It is about what is denied him or her in order to pursue their art. It seems to say, as an artist you can observe life but you cannot be a part of it. You must remain a step removed. And movies are not real. They are moments; they are memories.

I think the film, at least in its extended version, is less a film about a love of cinema than a film about the sacrifices demanded by art. And while it does not provide an answer, I think it also speculates on the relationship between life and art and which has greater value.

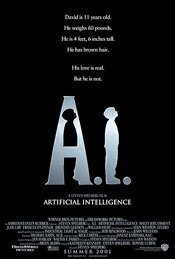

Spielberg, Kubrick and Artificial Intelligence: A.I.

I haven’t seen A.I.: Artificial Intelligence in a few years so I watched it again last night. My memory is poor but based on what I wrote (below) in 2002 and my vague recollection, this was a Stanley Kubrick project that never saw the light of day. (The Wikipedia entry suggests Kubrick himself felt the subject might be better suited to Spielberg.)

A brief online scan shows that since the DVD was first released back in 2002, there haven’t been any other editions. I don’t believe it is available yet in HD. That seems odd since it seems the kind of movie suited to HD. Here’s what I wrote back in 2002:

A.I.: Artificial Intelligence (2001)

While it is a flawed film, I think A.I.: Artificial Intelligence is the Steven Spielberg film I’ve most enjoyed. Like the Andrew Niccol film Gattaca, it’s a science fiction film that is about something and, like the best science fiction, it’s not about science but how we respond to science and what it creates.

It’s also a great movie to set against Spielberg’s earlier Close Encounters of the Third Kind in that the perspective is so different.

In a way, it relates to Spielberg’s earlier films in the way Shakespeare’s The Tempest relates to the earlier Shakespearean romances. The bright, awe-struck sensibility of a young man is now replaced by a darker (but not pessimistic), somewhat world-weary view of an older man. This is what happens when you make movies like Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan. While hope may remain, it has been conditioned by the darker aspects of reality, by an awareness of consequences that linger despite overcoming evil.

Of course, this is the movie that has caused so much discussion about what Stanley Kubrick would have done had he made the film. There seems to be a belief among some that Kubrick would have made a better film. I don’t think so, and I think Kubrick knew it.

Of course, this is the movie that has caused so much discussion about what Stanley Kubrick would have done had he made the film. There seems to be a belief among some that Kubrick would have made a better film. I don’t think so, and I think Kubrick knew it.

In fact, I think this movie is as good as it possibly could have been, and is probably much better than many think it is, precisely because it’s informed, to varying degrees, by both men. Spielberg’s mastery of a child’s viewpoint is what redeems the bleak world of a Kubrick production.

Kubrick’s masterful way of creating an almost Zen-like clarity of darkness defuses what could easily have devolved into an almost Disney-ish sentimentality. Together, the Spielberg and Kubrick sensibilities negate the excesses of the other and create a dark vision we can actually enter, identify with and travel along with.

It results, however, in a few jarring moments. In the first act, Spielberg gives us a pristine homage to the Kubrick style. In fact, it’s hard to image this is Spielberg directing and not Kubrick. The scenes are austere, cold, clinical, dispassionate. In the same way that Kubrick sets up a story by almost laying cards unemotionally on the table, Spielberg creates a collage of scenes almost documentary style. There are odd angles, off-putting lighting, and brief dialogue exchanges with awkward pauses that create a sense that we are seeing things voyeuristically, at imperfect but opportunistic moments.

It results, however, in a few jarring moments. In the first act, Spielberg gives us a pristine homage to the Kubrick style. In fact, it’s hard to image this is Spielberg directing and not Kubrick. The scenes are austere, cold, clinical, dispassionate. In the same way that Kubrick sets up a story by almost laying cards unemotionally on the table, Spielberg creates a collage of scenes almost documentary style. There are odd angles, off-putting lighting, and brief dialogue exchanges with awkward pauses that create a sense that we are seeing things voyeuristically, at imperfect but opportunistic moments.

In Kubrick films, he sometimes seems to show us moments that are not only not the moments we’re use to seeing, but the moments that occur between them. In other words, he uses the material others put on the cutting room floor, and discards what others would have used.

And then we’re into the second act and suddenly in Steven Spielberg’s world. The austerity is gone; it’s all adrenaline now. It’s the man who makes movies like Jaws and Jurassic Park rather than The Shining. I think this is because in the first act we’re seeing how we react to David, this robotic boy who seems so human. The focus is on our response (not as an audience, but as a individuals who make up a society) and that is pure Kubrick.

And then we’re into the second act and suddenly in Steven Spielberg’s world. The austerity is gone; it’s all adrenaline now. It’s the man who makes movies like Jaws and Jurassic Park rather than The Shining. I think this is because in the first act we’re seeing how we react to David, this robotic boy who seems so human. The focus is on our response (not as an audience, but as a individuals who make up a society) and that is pure Kubrick.

In the second act we see how we, as human beings (identified now with David) are affected by this response. It’s terrifying; it’s baffling. It’s nightmarish, and this is what Spielberg gives us, in the Spielberg style.

In the third act, we’re into something altogether different. It’s a strange fusion of Spielberg and Kubrick, of Close Encounters and 2001: A Space Odyssey. The end is mysterious but it’s also hopeful, in an odd and equivocated way. Frankly, I’m not quite sure what to think of the ending.

Spielberg hedges on the bleak ending but that is not a bad thing because the obligation to Kubrick, I think, conditions and mutes a happy ending. It’s probably also muted because of Spielberg’s awareness of the Holocaust where, though the evil is defeated, its consequences remain.

When I picked up A.I., I didn’t expect much. Following the utter rubbish of big DVD releases like Star Wars: the Phantom Menace and Planet of the Apes, I was expecting another great DVD package of a truly awful film. What a wonderful surprise to find a really good movie was on this 2-disc set. The one thing to be aware of is there are two versions out there: widescreen and pan-and-scan (full frame). But the packaging doesn’t really make it obvious so take care to pick up the version you prefer. (Hopefully, you aren’t one of those barbarians that prefers the full frame.)

When I picked up A.I., I didn’t expect much. Following the utter rubbish of big DVD releases like Star Wars: the Phantom Menace and Planet of the Apes, I was expecting another great DVD package of a truly awful film. What a wonderful surprise to find a really good movie was on this 2-disc set. The one thing to be aware of is there are two versions out there: widescreen and pan-and-scan (full frame). But the packaging doesn’t really make it obvious so take care to pick up the version you prefer. (Hopefully, you aren’t one of those barbarians that prefers the full frame.)

(This review was written in March of 2002.)

See also:

- Super-Toys Last All Summer Long (story A.I. is based on)

- A.I. – Artificial Intelligence on Amazon (Widescreen Two-Disc Special Edition)

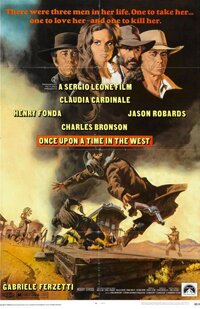

20 Movies: Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Look out. I’m back to westerns. I love them.

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

directed by Sergio Leone

From it’s incredible opening to the closing credits, Once Upon a Time in the West is a mesmerizing movie about westerns. In a way, it isn’t even about westerns. It simply evokes them with a stream of iconic images.

The movie takes a simple, almost cookie cutter story, and uses it as a basis (and excuse) for a film that is essentially concerned with western myths and iconography. (Sergio Leone had done this before, as in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.)

It’s a post-modern film; it takes a kind of deconstructionist approach to movie-making (which may seem a tiresome idea today but was unusual in 1969).

At the centre of the film’s narrative is Claudia Cardinale as Jill. Around her three other characters revolve: Henry Fonda as Frank, Jason Robards as Cheyenne and Charles Bronson as the man with no name (often referred to as Harmonica).

The owner of a railroad company, Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), hires a psychotic gunfighter, Frank (Henry Fonda) to get rid of anyone in the way of the completion of his railroad.

The owner of a railroad company, Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), hires a psychotic gunfighter, Frank (Henry Fonda) to get rid of anyone in the way of the completion of his railroad.

Frank does, by massacring the family of new bride, ex-whore, Jill.

With her new family dead, Jill must decide what to do with the land she has inherited. It seems worthless but proves to be very valuable, so valuable it is the reason her family has been killed. It’s a basic western formula: bad guys after the good guy’s land. He must defend it and himself, except in this case “he” is “she.”

At the same time, bad-guy Frank starts being stalked by a mysterious stranger (Charles Bronson). Frank doesn’t recognize him, he has no idea what the stranger wants. As for Jason Robards’ Cheyenne, he gets involved in all of this because Frank has framed him for the killing of Jill’s family.

At the same time, bad-guy Frank starts being stalked by a mysterious stranger (Charles Bronson). Frank doesn’t recognize him, he has no idea what the stranger wants. As for Jason Robards’ Cheyenne, he gets involved in all of this because Frank has framed him for the killing of Jill’s family.

For a film almost three hours long, it doesn’t seem much to work with. But Leone is interested in the storyline only to the extent that it provides him something to improvise on western themes and imagery. He plays with these and it is what he does with them that makes this such a great movie.

I can’t imagine how this would look in pan-and-scan form. Leone makes incredible use of the screen’s width, visually stretching it out with foregrounds oriented to one side and breathtaking backgrounds to the other.

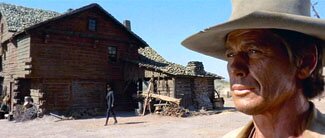

He also contrasts the breadth and spaciousness of his wide shots with the most extreme of close-ups. He shoots human faces almost as if they, too, were landscapes. The opening sequence is a spectacular example of this as he lingers on the bored killers’ faces. He shows us every detail from lines to whiskers. You almost get the sense he uses only two shots – very close or very long.

He also contrasts the breadth and spaciousness of his wide shots with the most extreme of close-ups. He shoots human faces almost as if they, too, were landscapes. The opening sequence is a spectacular example of this as he lingers on the bored killers’ faces. He shows us every detail from lines to whiskers. You almost get the sense he uses only two shots – very close or very long.

He also uses his trademark technique of drawing scenes out to their absolute limit. The opening goes something like eight minutes before anyone says anything and it is a scene simply about three guys waiting at a train station. You get an almost visceral sense of their tedium.

With scenes like gunfights, they are choregraphed to evoke iconic imagery and are paced, again, incredibly slowly to draw them out to their limits. When violence does erupt, it is explosive and very brief. Leone has little interest in violence itself but is obsessed with its rituals.

Whether the movie is about anything is debateable. Leone seems interested primarily in style and evoking the western. (Once Upon a Time in the West is littered with references to earlier Hollywood westerns like High Noon, The Searchers and numerous John Ford films. It’s even partly shot in Monument Valley where Ford shot so many of his westerns.)

Whether the movie is about anything is debateable. Leone seems interested primarily in style and evoking the western. (Once Upon a Time in the West is littered with references to earlier Hollywood westerns like High Noon, The Searchers and numerous John Ford films. It’s even partly shot in Monument Valley where Ford shot so many of his westerns.)

If there is a comment in the film, perhaps it is a critique of myths of America. In the film, everyone is dissatisfied. Everyone wants something more, from the railroad baron and his hired killer Frank, to the woman Jill and Jason Robards. In the land of the free, no one seems to be content with their lot (except, perhaps, for the murdered McBain.)

There may be something to the use of the railroad, too. Its arrival signals the end of the mythological West and the beginning of the modern age in the last American frontier. The train represents encroaching European civilization and the end of the mythical West, just as the film Once Upon a Time in America is a eulogistic end of the western.

There may be something to the use of the railroad, too. Its arrival signals the end of the mythological West and the beginning of the modern age in the last American frontier. The train represents encroaching European civilization and the end of the mythical West, just as the film Once Upon a Time in America is a eulogistic end of the western.

But in the end, the film is simply a great homage to westerns, as well as a kind of eulogy to them. It’s a stream of riveting images; an almost symphonic evocation of filmmaking style.