It’s hard to think of John Wayne and romance at the same time. The image of one and the image of the other don’t rest well side by side; one seems to negate the other.

True Grit: the last old western?

In some ways, the idea of the Coen brothers redoing True Grit gives me the willies. I would have been 12 or 13 when the Henry Hathaway/John Wayne version came out so it has a kind of nostalgic quality for me. (Believe me, I loved the movie when it came out.)

Unless scheduling changes, the Coen’s True Grit (which stars Jeff Bridges) will be out around Christmas so we’ll know soon enough how the two movies look set against one another. It’s worth noting, however, the movie they are making is not really a remake. It’s hard to imagine the Coens having any interest in that.

From what the publicity and interviews are saying, their movie will be from Mattie’s perspective, the 14 year old girl, and it is an interpretation of the book by Charles Portis, not the 1969 movie.

My guess is that the sunny, bright look of the 1969 version will be toast in the Coen movie. In the meantime, here are some meandering thoughts on the 1969 movie, True Grit.

True Grit

Directed by Henry Hathaway

Distances to cross; troubles to overcome; wrongs to be made right: that’s a western. Good guys, bad guys, horses, boots and guns firing. They all go into the mix because the best westerns are morality tales told within adventures. They are also simple.

True Grit has all these elements and delivers all those things. It also has two old school boys who know their business: actor John Wayne and director Henry Hathaway. Both were nearing the ends of their careers and both had been through a life of working in Hollywood – the old Hollywood. Both were also in a world that was changing, a world enthused about change, and working in a business, cinema, that was enthusiastically embracing change. (Well, the younger parts of it were.)

The movie Hathaway and Wayne made, then, is a kind of reminder that it’s best not to throw the baby out with the bathwater, to use an old expression. True Grit is such an old style western, complete with its swelling strings as riders crest a hill, it could easily become parody.

Yet somehow it doesn’t. I’ve referred to some films as comfort movies and this is one of them. It doesn’t aspire to change the world of cinema. It simply wants to tell a good story.

I think what I like most about this movie is that it is so unapologetic about what it is: an old style western; an old style story. Roger Ebert says this is a movie, not a film. He’s right.

The IMDb synopsis is as simple as the movie: “A drunken, hard-nosed U.S. Marshal and a Texas Ranger help a stubborn young woman track down her father’s murderer in Indian territory.” That’s it; that’s the story this movie tells.

A man is murdered. His 14 year old daughter (Kim Darby) wants him caught and dealt with so she looks to enlist a man with “true grit” to do the job. That man is Rooster Cogburn (John Wayne), a cranky, drinking, one-eyed U.S. marshall. He’s joined by a Texas Ranger (Glen Campbell) who is after the same man but for a bigger reward – the one available in Texas where the scoundrel murdered a senator.

What they don’t anticipate is that the daughter, Mattie, is determined to join them. They aren’t happy with this and try to lose her until it’s more than clear that there is more to Mattie than they expect from a young girl.

What we get on screen through the wonderfully straight-forward directing of Henry Hathaway is story of, yes, grit. It’s about tenacity and resolve and in its way a code of honour. The hunt for the killer, while resembling a revenge movie, is a bit of misdirection. The movie is really about the relationship between Rooster and Mattie.

As far as acting goes, Glen Campbell is in over his head here but holds his own to some degree. But with the great performances by John Wayne and Kim Darby, it doesn’t really matter however.

Wayne received an Oscar for this movie and while you can argue whether it was for his career or his actual performance in True Grit, what he puts on screen in the movie is marvelous to watch. He is so at ease with this character it’s hard to believe acting is work. I think what he gives us, thanks to the character he plays, is a synthesis of a number of characters he’s played in movies like The Searchers, Rio Bravo and even Donovan’s Reef. I suppose you could argue that the Oscar was for his career because, in a sense, the role is his career.

In the end, this is a good movie because it is a good story. It’s also a fascinating movie seen as “the last old western.” Look at how it is shot: bright and beautiful. Notice how workman-like the shots are framed. The camera is only interested in capturing the performance. It wants the performance to tell the story not the elements of film like lighting, angles, camera movement. It’s functional and happy to be so.

I’ll be interested in seeing the Coen brothers’ take on True Grit when it comes out. It should make for an interesting comparison between the film they’ve made and the one Henry Hathaway made. My guess is the two, taken together, will be a revealing study in style and sensibility between eras.

On Amazon:

- True Grit – Amazon U.S.

- True Grit – Amazon Canada

Jean Arthur and John Wayne

After having it on my computer for about two months in a half-finished state, I’ve finally posted my take on A Lady Takes a Chance (1943). It stars Jean Arthur and John Wayne and, yes, it’s a romantic comedy.

It’s not, however, the best romantic comedy. It’s pretty mediocre. However, both Arthur and Wayne are wonderful, each in their own way.

If you are a fan of either actor, you should see this one. The film, as a whole, is pleasant but not anything that would have change the world of cinema. My review can be found here.

Donovan’s Reef: Fisticuffs anyone?

I took a shot at assessing another John Wayne movie (since I’d been doing quite a few of those lately). Here’s what I came up with:

Donovan’s Reef (1963)

This is a difficult film to defend, much less recommend, for many reasons, most of which have to do with director John Ford. Still, if I may refer to Glenn Erickson who, in his review, refers to Andrew Sarris in The American Cinema, “…Donovan’s Reef was like some kind of heaven that Tom Doniphon and Liberty Valance, both fun-loving uncivilized types, had retreated to in the afterlife. And it’s the key to appreciating this broad comedy.”

This is a difficult film to defend, much less recommend, for many reasons, most of which have to do with director John Ford. Still, if I may refer to Glenn Erickson who, in his review, refers to Andrew Sarris in The American Cinema, “…Donovan’s Reef was like some kind of heaven that Tom Doniphon and Liberty Valance, both fun-loving uncivilized types, had retreated to in the afterlife. And it’s the key to appreciating this broad comedy.”

In other words, Donovan’s Reef is fantasy. It also recapitulates many of the themes and sentiments that characterize the John Ford canon. You could call it a kind of executive summary. Unfortunately, many of those themes and sentiments are more than a little disagreeable, even offensive, to a modern sensibility, like the racial and gender characterizations.

Compounding that is the structure and style of the film which is somewhat clunky. I think Erickson describes it pretty well when he writes that it is, “…a surreal, almost abstract progression of kabuki-like rituals from the world of John Ford.”

The movie comes across as a collection of set pieces that are only loosely tied together. It’s almost episodic. These set pieces, however, are like a highlighting of key aspects of Ford’s work – again, almost like an executive summary. Many of these conclude with brawls – many of them seem to be excuses for brawl scenes – fights that involve almost everyone and where no one gets hurt.

The movie comes across as a collection of set pieces that are only loosely tied together. It’s almost episodic. These set pieces, however, are like a highlighting of key aspects of Ford’s work – again, almost like an executive summary. Many of these conclude with brawls – many of them seem to be excuses for brawl scenes – fights that involve almost everyone and where no one gets hurt.

It’s all set in an idyllic, mythical South Seas world called Haleakaloa. It stars John Wayne and Lee Marvin as two brawling pals who like drinking and fighting, and being their own men. There is a romance that reiterates Ford’s vision of relationships between men – antagonistic, but in a charming way.

But is it a good movie? I would have to say no even though I did enjoy it. Despite the similarity to North to Alaska, the film it most reminds me of is Hatari! That movie, directed by Howard Hawks, is long and meandering. It seems to be more about spending time with the characters. This how Donovan’s Reef strikes me. The story is flimsy at best. The movie is more about spending time with Wayne, Marvin and, in behind the scenes, Ford in a fantasy paradise. It’s almost like sitting around with old friends and having a few beers.

This is why I can enjoy the movie. If you’re familiar with Ford/Wayne movies, if you grew up with them and liked them, you can enjoy the movie, though you couldn’t credibly argue for it being a “good” movie. At least, I don’t think so.

And if you didn’t grow up with these guys, if you’re unfamiliar with the sensibility and are unwilling to turn a blind eye to some of the stereotyping and so on (rather like sitting down with a politically incorrect grandfather who, smiling, unthinkingly throws out inappropriate remarks) … No, you won’t like this movie.

And if you didn’t grow up with these guys, if you’re unfamiliar with the sensibility and are unwilling to turn a blind eye to some of the stereotyping and so on (rather like sitting down with a politically incorrect grandfather who, smiling, unthinkingly throws out inappropriate remarks) … No, you won’t like this movie.

But then, the movie was never made for you. It’s more like a greeting card sent to old friends from Ford, full of the John Ford “stuff,” from the characters to the scenes.

1½ stars out of 4.

3 Godfathers: A western as Christmas fable

Having come across 3 Godfathers in a number of “top Christmas movies” lists, I decided to watch it. A second time. I had watched it about two years ago but I couldn’t recall it, and definitely didn’t recall the Christmas aspect. Now, having seen it again, I see the Christmas angle but I don’t personally consider it a Christmas movie. It plays like a western – an odd one, granted – and with no Christmas “feel,” at least not for me. Here’s the review I wrote:

Review – 3 Godfathers

The 1948 John Ford movie 3 Godfathers is, if nothing else, damn odd. And, to be honest, I’d have to say it’s ill-considered. It’s a western as Christmas-tale where three outlaws become something akin to the three wise men of the New Testament, but not really, and in the process reveal themselves as three bad guys who are really, really nice once you get to know them.

The 1948 John Ford movie 3 Godfathers is, if nothing else, damn odd. And, to be honest, I’d have to say it’s ill-considered. It’s a western as Christmas-tale where three outlaws become something akin to the three wise men of the New Testament, but not really, and in the process reveal themselves as three bad guys who are really, really nice once you get to know them.

The film is dedicated to Harry Carey. John Wayne is the star. It co-stars Carey’s son, Harry Carey Jr. (in what I believe to be his first film). It also co-stars Pedro Armendáriz. The three, Wayne, Carey Jr. and Armendáriz, are three outlaws who arrive at the town of Welcome, Arizona, roughly around Christmas time, with the intention of robbing the bank.

When they first arrive they meet a friendly fellow with whom they begin to josh and converse. As the encounter ends, they discover he’s the town’s sheriff (Ward Bond), a man who has a pretty good idea of what kind of men they are and what they’re intentions might be.

So they rob the bank and in short order the sheriff has a posse out after them. Soon, the sheriff realizes that Wayne’s character, Robert Hightower, is a clever man and the chase becomes something of a game for him, the sheriff. It’s a challenge – he looks forward to catching Wayne and playing chess once he’s in prison.

The chase takes the outlaws out into the desert where they are in search of water and shelter. It’s not easy – one of them is wounded. Each time they come upon water, the sheriff and the posse are there ahead of them so they have to go searching for water elsewhere.

The chase takes the outlaws out into the desert where they are in search of water and shelter. It’s not easy – one of them is wounded. Each time they come upon water, the sheriff and the posse are there ahead of them so they have to go searching for water elsewhere.

So far, so good. It’s an average western – not great, but not bad. But then they come upon a dying woman who is about to give birth. They help her with the birth. The child is born but his mother is dying. Before she does, however, she names the child after the three outlaws, appoints those same outlaws as the child’s godfathers, and makes them promise to care for the child.

The story movie now takes a weird turn where the western continues but a variety of religious elements – symbols and speeches and so on – begin to populate it. (These actually begin back with the woman giving birth to her baby – it is Christmas time.)

The three men care for the child passionately. Two of them perish in the end, for the sake of the child, and the third, Wayne, all but dies. He manages to survive, saving the child, but is caught by the sheriff. He’s taken back to the town of Welcome where he will face trial and a potential sentence of 20 years if found guilty.

The odd thing here (as if things haven’t been peculiar enough) is everyone is friendly, best buds, even though Wayne is in jail and going to court.

As might be expected with a Christmas film (that never really feels like a Christmas film), there is a happy ending to it all.

And it’s all just so damn odd.

On the plus side, however, I think this movie has one of the most interesting performances from John Wayne. He seems more emotive than we usually see him, and there is more animation in his face than usual. He has a nice speech in a scene where he tells the other outlaws about finding a pregnant woman in an abandoned wagon. It’s hard to say whether it’s one of his better performances, though, since the film is so strange. Is he good? Is it over the top? I really don’t know.

I can say this, though: Ward Bond is very good. And so is Harry Carey Jr., especially for a first film. (It’s not his fault the part is written the way it is.)

Also excellent in the film: the cinematography. The shots in the desert are really quite magnificent. The visual look of the movie is very John Ford, very good.

Overall, however, I’d have to say this is a wrong-headed film. It’s the wrong kind of story for John Ford. Apart from being a Christmas western (which just sounds weird), this essentially sentimental, feel-good story is Frank Capra country, not John Ford. Ford doesn’t seem to finesse this kind of story where we can accept the sentimentality – probably because of the western austerity and harshness that plays through most of the film.

Mind you, in its historical context, the Christmas aspect might have played better to an audience of the day than a contemporary one. But for me this is a curious movie but not a particularly good one.

2 stars out of 4.

John Wayne heads north – booze and brawls ensue

Directed by Henry Hathaway

Directed by Henry Hathaway

This movie, North to Alaska, is a difficult one to account for. I really like it a lot. But I can’t think of a single cinematic merit it has going for it. Essentially, if you don’t like John Wayne’s later movies, especially the comic ones, you won’t likely take to this film. In fact, you may take a strong dislike to it because it’s corny and wildly sentimental. But if you do like John Wayne …

From something I read somewhere on the Web (does it get more definitive or authoritative?), North to Alaska was one of the first, if not the first movie of John Wayne’s later career, the older Duke, as far as his comic films go. Later, there would be films like, Hatari!, Donovan’s Reef (his last with John Ford) and McLintock!.

In this movie, Wayne is teamed with Stuart Granger. They’re Sam (Wayne) and George (Granger), two guys who strike gold in Alaska. Both are elated, George so much so he sends Sam to Seattle to bring back his fiancé, Jennie. Unfortunately, in Seattle Sam discovers she’s already married. She wasn’t nearly as serious about the engagement as George was. Sam, determined not to see his friend disappointed, brings back a saloon dancer instead, Capucine (Michelle Bonet).

There are, of course, complications. For instance, Sam and Capucine fall in love, complicating Sam’s determination to take care of his friend. And there’s Frankie Canon (Ernie Kovacs), a scoundrel looking for ways of cheating Sam and George out of their claim.

In the middle of all this there is a good deal of brawling between the boys of the Alaskan town (including Sam and George), as well as romantic gamesmanship between Sam and Capucine.

In the end, it’s romantic fantasy – an Alaska that didn’t exist (except in the most broadly interpreted sense) and a feisty and unlikely romance. But realism wasn’t what they were going for. It’s intended as escapist entertainment. So you never see the reality of brawling like that or of drinking that way.

On that basis, it’s a fairly engaging film and pretty well succeeds at what it aims to do. It may come across as somewhat anachronistic to anyone who didn’t grow up with John Wayne movies. The sensibility is definitely not contemporary.

If this was the first of the later John Wayne comic films, it’s easy to see the template established: a bit of “battle of the sexes” romance, a lot of phony-baloney brawling and a good deal of drinking that appears to have only brief ill-effects, and only if the plot calls for it.

It’s fantasy but it’s fun. Movies like this are really about giving the audience the John Wayne they expect, in situations that underline the image, and doing it in a light-hearted way. In a way, it’s a bit like teasing a beloved friend or relative.

Yes, I think that’s what I’d say these movies are: light-hearted teasing of the John Wayne image that underscores just how beloved he was.

2½ stars out of 4.

John Wayne and Donna Reed in a muddle

The few reviews found online of Trouble Along the Way, a 1953 movie starring John Wayne and Donna Reed, generally agree: fans of the Duke will likely enjoy it but its saccharine quality will probably be off-putting for anyone else. They also all seem to grade the movie as so-so, at best.

I can’t say I disagree with that assessment though, honestly, I liked the movie. It’s definitely sentimental. It’s sort of a romance that is not a romance, and a sports movie that isn’t a sports movie. And maybe that’s why the movie ends up being considered so-so. It’s not really sure what it wants to be.

I was a bit thrown at first because, based on the little I had read, I thought this would be a sports movie: John Wayne as coach of a luckless college football team that makes good. Given the year it was made (1953), I thought it might have been a precursor of sorts to the standard sport movie we see these days. You know the one: the big uplifting ending where everyone cheers as the guy or guys, gal or gals, triumph despite mountainous obstacles.

It was not that. It did, however, have a number of football scenes. (Interesting, too, seeing football before it evolved into what it is now. I’m pretty sure they were stock footage, however.)

As the movie starts, you might think you’re about to see a Bells of St. Mary’s kind of film, minus Bing Crosby and the singing. It focuses on Charles Coburn as Father Burke, the top banana at St. Anthony’s College. The college is struggling. Father Burke thinks it might be saved using the school’s football program (which is in pretty sad shape).

Enter the Duke, reluctantly. Wayne plays an ex-coach college football coach who has been banned from the major conferences. He has a big heart, however, hidden behind an occasionally gruff exterior (the usual John Wayne thing). But his focus in life is his daughter, a streetwise young girl who is equally devoted to her father. But Wayne is involved in a custody battle.

Enter Donna Reed, a Children’s Court officer who has a low opinion of Wayne and his parenting skills. Romantically, this is the basic set up: an antagonistic relationship that evolves as she eventually discovers Wayne isn’t the negligent father she thought.

He storylines interweave to a degree but overall come across as separate lines battling for attention. In the end, the sports line loses out. But it’s the sense of disparate parts that give the film a confused feel, despite the number of ways they connect. Is the movie about the romantic relationship or is it about the sports/save-the-school story?

Oddly, the movie was directed by Michael Curtiz, the man who gave us Casablanca. You get the sense, however, that this movie is a definite factory project. Go through the motions, cut it together and get it out fast.

And yet, it curiously has its charm. It’s a hard movie to defend, but it’s also difficult to slam it. It’s a middling movie. It’s charm comes largely from three elements: 1) John Wayne’s performance, 2) the on screen relationship between Wayne and his daughter and, finally, 3) Charles Coburn’s Father Burke – a cliché, yes, but a winning one, at least in the context of a movie of that period.

Speaking of period, the movie is also worth seeing for this aspect. It reflects pretty well the Hollywood ideal of America of that time (1953) which, I think, reflected pretty well how average people wanted to see America back then. Realistic? Nope, but few people go the movies to see reality portrayed.

2 stars out of 4.

Two last comments:

- I need to watch the ending again. It confused me but I’m not sure if that’s because the ending is actually confusing or I was distracted by a dog that wanted to go outside.

- I find the title Trouble Along the Way baffling. How does that relate to anything we see on screen? What does it mean

Revisiting Rio Bravo

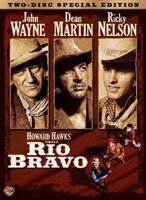

Although I’ve had the relatively recent release of Rio Bravo (Two-Disc Special Edition), it has taken me most of the summer to get around to actually watching it. And I actually picked up Rio Bravo (Two-Disc Ultimate Collector’s Edition), which is the same thing just with more stuff like a comic book of Rio Bravo included. Though heaven knows why I would want that. Anyway …

Although I’ve had the relatively recent release of Rio Bravo (Two-Disc Special Edition), it has taken me most of the summer to get around to actually watching it. And I actually picked up Rio Bravo (Two-Disc Ultimate Collector’s Edition), which is the same thing just with more stuff like a comic book of Rio Bravo included. Though heaven knows why I would want that. Anyway …

The point is I finally watched it and no matter how many times I see this movie, I always love seeing it again. I haven’t had a chance yet to watch the various special features (though I’m looking forward to those, especially the Howard Hawks piece), but I’ve seen the movie. A few years back, I wrote a review of it and it is here.

I love this movie!

I also love this, from Rio Bravo:

The Shootist – John Wayne’s last film

For me, The Shootist (1976) is a funny movie. Not funny “ha-ha” but funny in the oddball sense. I really enjoyed it. It’s a good, maybe even close to great movie. But at the same time, there are aspects of it that don’t quite work for me.

I think what I have problems with are Don Siegel’s direction. On the one hand, it’s perfect. He tells the film’s story exactly as he should. It’s the tale of a gunman, a “shootist” who, in his later years, finds out he has cancer and is dying. The movie focuses on his final days.

This makes it a very character driven film. And this is how Siegel directs it. Being a mid-seventies film (and being as Siegel is the man who gave us Dirty Harry), there is a good deal of reliance on the hand held, realistic looking “in-the-moment” kind of film work that was common with certain films back then.

But … The problem I think I have is that Wayne’s character, John Bernard Books (based loosely on John Wesley Hardin), is a character whose story, in the world of cinema, is dependent on previous Hollywood movies. In other words, in order for the character and his situation to resonate, we have to refer back to what Hollywood has established – part of the reason why Wayne is perfectly cast in this role.

But the movie isn’t really shot or put together like a Hollywood western. It has the look of something much more realistic, far less mythic.

And for me this didn’t quite work. I found it a bit off-putting. (Though I will say that, near the end of the film, Siegel uses a handheld, ground level shot to change perspectives that works brilliantly given that it’s the sort of change you’re not really supposed to make.)

But that’s not to say I didn’t like the film. The truth is, I loved it and I loved John Wayne in this role. He was made for it. And like many actors, the older he got the more effortless his performances became and here, in The Shootist, it comes across as utterly effortless.

On the whole, despite my qualms, this is a wonderful western and a great character piece where we get to see John Wayne, not to mention Lauren Bacall and Ron Howard and an array of other superb Hollywood stalwarts, give a tremendous, moving performance.

A gunfighter’s last days. A man who is dying and knows it. What does he do? How does he feel? How does it play out?

That’s The Shootist.

And in addition …

As a review of this film on filmcritic.com reminds me, there is an fascinating behind the scenes story to this film about an old gunfighter dying of cancer. John Wayne, who plays that old gunfighter, was himself dying of cancer at the time he made this film. This is recounted in the relatively short but very interesting documentary that is part of the DVD’s special features. (Actually, it’s essentially the only special feature on the disc.)

You can get The Shootist individually or, as I did, part of The John Wayne Centennial Collection, which contains eight of the Duke’s movies (and some pretty good ones at that).