Clever and sly, Witness for the Prosecution has the appearance of being a modest little film that manages to sneak up on you with great performances and a great ending.

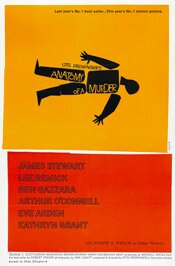

Who dunnit? What did they do? Who cares? – Anatomy of a Murder

It’s Day 4 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. And if you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down this page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

What I like about Anatomy of a Murder is that every so often a friend will say something like, “… This movie I saw on TV was so good …” As they describe it I realize what movie they mean and remark, “That’s Anatomy of a Murder.”

What I like about Anatomy of a Murder is that every so often a friend will say something like, “… This movie I saw on TV was so good …” As they describe it I realize what movie they mean and remark, “That’s Anatomy of a Murder.”

“Yeah! That’s what it was called!”

I mention this because many of these people usually have to make what I called cognitive adjustments in a post not long ago. They don’t like “old movies.” Black and white, pacing, sensibility … all kinds of things can impede us from entering a movie because we are used to one kind of film (contemporary) and something old, foreign or both requires some readjustment.

Some require less adjusting than others, however. Anatomy of a Murder is one of them. Despite being a movie from 1959, it feels very modern. Part of it is in the subject matter; part of it is in the way it handles and views that subject matter; it’s partly Duke Ellington’s music for the soundtrack.

Whenever I watch this movie I find myself wondering what is going on behind the eyes of the main characters. I never figure it out. Everyone is so cagey and ambivalent. It’s as if none of them have a moral compass. They exist in a world where that is just excess baggage and only gets in the way.

What follows are the ramblings I made about the movie about ten years ago as I tried get my take on …

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Anatomy of a Murder (1959)

Directed by Otto Preminger

Although I was confused about where exactly Anatomy of a Murder was taking place (Michigan, it seems), it’s a great, enthralling courtroom drama of the noir variety.

It has a great late 50’s black and white look, somewhat similar to Kiss Me Deadly, though this is a far better film. (I wouldn’t take the similarity very far either. It’s just something in the period look they have in common.)

Jimmy Stewart is great in this movie. Some argue it’s his best performance, and there’s something to be said for that.

He has the laconic air and halting speech he’s famous for and it works well here as a kind of strategic approach to getting at the truth of things. It catches others off guard.

He’s a small town lawyer, formerly chief prosecutor (holding the post for ten years). Why he’s no longer in the position isn’t really explained but you get hints his leaving was under a shadow, or at least troubled somehow.

It seems all his character does now is fish, drink and take small, penny-ante cases to pay his bills (which he does badly). Then a big case falls in his lap.

After taking a long time asking questions, mulling things over, and in no apparent hurry to get involved, he finally takes the case and the film really gets underway. (In fact the first portion of the film is a bit slow.)

The case he has is this: a woman (Lee Remick) has been raped. Her soldier husband (Ben Gazzara) has gone out and shot the alleged rapist dead. The soldier is now on trial for murder. Stewart’s job is to defend the soldier. But as he points out to his client, there is really no defense for him … except, possibly, one. The murder being deliberate (an hour after hearing from his wife about the rape), he can’t argue passion. The time element makes it pre-meditated. Gazzara’s only hope is to argue for insanity – an “irrepressible urge.”

There are various complications along the way, including help for the prosecution via the Attorney General’s office in the person of George C. Scott who plays his role with relish, informing it with a kind of conniving smugness.

What really sets Anatomy of a Murder in the noir category is its overarching moral ambivalence. If you pay attention as you watch, you realize that there really are no “good guys” here – not even Stewart, though his performance and the direction align the audience’s sympathies with him.

But he’s defending a man who has committed murder. He is trying to get him off scott free.

You know by what Gazzara says and doesn’t say, and by his performance, that he is guilty. And you know Stewart knows this when he takes the case. The trial is really about playing fast and loose with the law. And both sides in the case do this.

In the case of the woman who was raped, the incident seems to have meant little more to her than stubbing a toe. It’s as if somewhat had given her a quick kiss, not violently raped her.

Of course, her character is a victim in other ways. She’s slatternly and flirtatious and you know from certain scenes, and by the way Remick plays her, she is a woman trapped by abusive men. She’s lonely and seems to gravitate toward men who treat her badly. Her relationship with her husband, Gazzara, suggests domestic violence, though it’s implied and not overtly stated.

At the end of the movie, while there is a resolution (the trial ends) there is no moral resolution. Nothing has changed. Justice has been thrown out the window. The victim will continue to be victimized. While the man who raped her may be dead, she continues on with the one who abuses her.

(It’s interesting to see how her character changes in the film, allows us to see more of who she is, such as her lonliness, then at the film’s end, as she meets Stewart’s character going up the stairs to hear the verdict, she’s back to her previous clothing and flirtatious manner. Again, nothing has changed.)

Despite a few Hollywood elements to lighten the tone at the end, this is a dark film. The hero, Stewart, at the end is little better than those he has been up against.

The movie concludes with a wry look from Jimmy Stewart and a tone of bemused hopelessness as if the director, Otto Preminger, is saying, “That’s people for you. What can you do?”

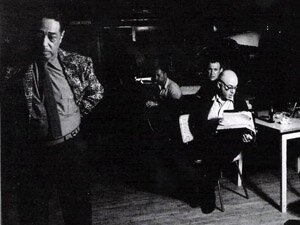

One last note … The movie’s music was composed by Duke Ellington and it really gives it a unique quality, particularly for the period it was made, and adds to the movie’s overall atmosphere. Ellington also has an uncredited appearance in the movie as Pie Eye, owner of a roadhouse where Jimmy Stewart’s character sometimes goes to play piano.