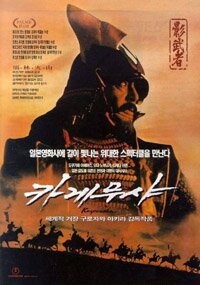

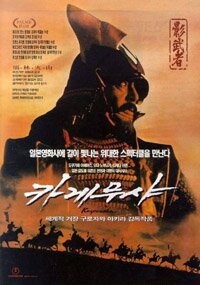

This is a review I wrote a few years ago when I first picked up the DVD of Kagemusha and saw it for the second time, some twenty years after first seeing it. I think I might write something quite different today.

Somewhere on my computer I have a post about old black and white movies and “foreign” films and how, in certain ways, they involve cognitive barriers we have to get past to enjoy the movie. In the case of Kagemusha, it would be the language, Japanese (unless, of course, you speak Japanese). You don’t understand the language; you follow subtitles. That creates a barrier of sorts that you have to adjust to.

Kagemusha is one of the first movies of the subtitles kind that I saw and probably the first where the adjusting was almost non-existent. It was so visually brilliant I was enthralled from the start. Prior to Kagemusha, my movie experience was almost exclusively Hollywood. I’m still essentially a Hollywood formed viewer but it is probably Akira Kurosawa more than any other director that brought me into a world of film beyond the restrictive Hollywood definition.

Kagemusha (1980)

Kagemusha (1980)

directed by Akira Kurosawa

I probably saw the movie Kagemusha first back in 1980 or 1981, when it was first released in North America with 20 minutes removed from the film Akira Kurosawa made. At the time, it knocked me for a loop.

It was the first Kurosawa movie I had seen. It was also the first samurai film I had seen. I don’t recall many other movies that so impressed me visually. Also, back then, my cinematic references were almost entirely western, as in Hollywood, with maybe a few Fellini films tossed in the mix.

So here was a colourful samurai movie in Japanese with English subtitles. Going in, I was a bit trepidatious. Going out, I was ga-ga.

That was more than twenty years ago. I’ve not seen Kagemusha since, not till last night when I watched the Criterion DVD – Kurosawa’s fully restored, 180 minute version in a transfer that is outstanding.

In those intervening twenty odd years I’ve seen many more kinds of film, many more samurai films and many more Akira Kurosawa films, including some of his non-samurai movies like Ikiru.

In those intervening twenty odd years I’ve seen many more kinds of film, many more samurai films and many more Akira Kurosawa films, including some of his non-samurai movies like Ikiru.

So the virgin quality of my first experience of Kagemusha is gone; it’s visual impact has been lessened in that sense. On the other hand, while no expert I’m still a bit more visually conversant than I was then, a bit more attentive and aware, not so impressed by something that looks “cool.” In that sense, the visual impact of the movie has been heightened.

The movie is about a thief, one condemned to die by crucifixion, but is spared because he looks so much like the leader of the Takeda clan, Shingen. It is Shingen’s brother who has discovered the thief’s resemblance, the same brother who has also been acting as Shingen’s double (a kagemusha) as a strategic tool in their conflict with other clans.

The movie is about a thief, one condemned to die by crucifixion, but is spared because he looks so much like the leader of the Takeda clan, Shingen. It is Shingen’s brother who has discovered the thief’s resemblance, the same brother who has also been acting as Shingen’s double (a kagemusha) as a strategic tool in their conflict with other clans.

The thief does become a kagemusha for the Takeda leader but then Shingen is mortally wounded by a sniper. Before he dies, Shingen makes his final wish known – to not reveal the fact of his death until three years after he has died and to use that time to pull back and consolidate the Takeda position.

The thief then becomes a kagemusha for Shingen in earnest. He does it so well, he fools almost all and thus makes the other clans uncertain – fearful of Shingen and confused about his intentions.

As the film evolves, it becomes a meditation on the nature of power and of leaders while at the same time moving forward with a tragic, inexorable determination.

I’m struck by several things about Kagemusha (including how long the movie is). I suppose more than anything I’m taken by how controlled and deliberate it seems, how managed each shot is.

It begins with the very first scene. It’s a fairly lengthy one where the warrior Shingen and his brother (who has acted as Shingen’s double in the past) first meet the kagemusha (“double” or “shadow” – hence the film’s title sometimes being referred to as Kagemusha: the Shadow Warrior).

The scene is a single, static shot – no cuts, no camera movement. The actors sit Japanese style on the floor and are exactingly positioned to compose the shot. They make a set of three elements placed deliberately in the foreground – two (the brothers) are centre and left. Of the two, one (Shingen, in the middle) is slightly above. The third characer or element, the kagemusha, is off to the right, also below the middle element, Shingen.

This composition of three, or variations of it, occurs over and over throughout the movie. (If I recall correctly, we also see it used in the opening of his next movie, Ran.)

Other than simply liking this kind of composition, I’m not sure what significance it has for Kurosawa. For me, however, it communicates order and a sense of control, or at least its illusion.

It contrasts starkly with where Kurosawa’s film ends up taking us – the disorder of the battlefield after the conflict, and perhaps even the movie’s final image of the kagemusha being carried off by a current in the sea, that image composed in such a way as to severe the “canvas” against which the compositions of three were placed. (Alright, that last bit may be a stretch.)

It contrasts starkly with where Kurosawa’s film ends up taking us – the disorder of the battlefield after the conflict, and perhaps even the movie’s final image of the kagemusha being carried off by a current in the sea, that image composed in such a way as to severe the “canvas” against which the compositions of three were placed. (Alright, that last bit may be a stretch.)

In his later samurai movies (Kagemusha and Ran), Kurosawa takes a very painterly approach, and also a very deliberate one. As mentioned, the film struck me by its length. This is partly because it is long – three hours – but also because it begins slowly and (to repeat myself) deliberately as the beginning goes through a lengthy exposition.

But it’s not simply story exposition. It’s visual exposition too, those brilliant compositions of order. Interestingly, contrasted against the structural order of the way each scene is composed is the content, or story itself, which is somewhat confusing as we have several people playing, to some degree, one character – Shingen, the brother and the kagemusha. In the first half hour, it’s not difficult to get these confused.

For me, Kagemusha is a wonderful, if somewhat difficult movie. I think Ran is the better film. Kagemusha, however, is a film Kurosawa needed to make in order to get to Ran. Many of the visual ideas about composition and colour are first explored here. The movie is also an initial iteration of the theme of chaos and order, their roots and the illusions that attend the ideas of power, control and position.

For me, Kagemusha is a wonderful, if somewhat difficult movie. I think Ran is the better film. Kagemusha, however, is a film Kurosawa needed to make in order to get to Ran. Many of the visual ideas about composition and colour are first explored here. The movie is also an initial iteration of the theme of chaos and order, their roots and the illusions that attend the ideas of power, control and position.

Finally, Kagemusha is well worth seeing if only to sit back and let absolutely stunning images wash over you. This is one of the best looking movies I’ve seen.

See: 20 Movies — The List