Relationships, sex, communists and, somewhere off camera ,World War II — The Male Animal from 1942 is a curious film to say the least. It comes with some pretty impressive credentials, however, including its stars as well as its origins: based on a play by James Thurber and a screenplay with writers that included the Epstein brothers.

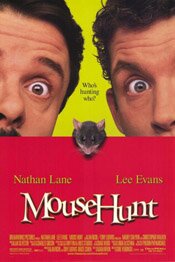

Loving and hating Mouse Hunt

Mousehunt (1997) is a funny movie in both senses of the word. It is funny “ha ha,” and it is funny peculiar.

Mousehunt (1997) is a funny movie in both senses of the word. It is funny “ha ha,” and it is funny peculiar.

For me, it is one of the funniest movies I’ve seen. Ever. I can’t think of many movies, if any, that have made me laugh out loud like this one does.

Other people, however, either like it as I do or absolutely hate it. There is no middle ground. I don’t think I’ve met anyone that felt it was “okay” or “not that good.”

They love it. Or, they hate it.

I suspect it is because the humour is so broad and slapstick. Though there is also some very funny dialogue, it is very visual humour. To an extent, it could be compared to the Three Stooges — at least as far as the visual jokes go.

Oddly, though I love Mousehunt I’ve never been a big fan of the Stooges.

Nathan Lane and Lee Evans are two brothers, Ernie and Lars Smuntz. They inherit a dilapidated house when their father dies along with a string factory that desperately needs modernization. The brothers don’t always agree. One reason is that Lars is simple and kind, for the most part, whereas Ernie is cynical and self-centred.

It’s decided (thanks to Ernie) that they will fix the house up, at least superficially, and then sell it quickly to get whatever they can for it. Then they find out it has historical significance — it’s “the missing Larue,” designed by a famous architect — and worth boatloads of money. They’re thrilled, however …

There is a mouse living in the house and it has other ideas.

As Ernie says later in the movie, after numerous painful attempts to get rid of the mouse, “He’s Hitler with a tail. He’s “The Omen” with whiskers. Even Nostradamus didn’t see him coming!”

The movie builds from one attempt to another, each more elaborate, each with a more disastrous result. There is one sequence when the brothers bring in ‘Caeser, the Exterminator’ (Christopher Walken) to rid the house of the mouse that is hilarious. Walken gives wonderfully oddball performance as Caesar.

But it’s Lee Evans as Lars that really stands out for me. Tall and gangly, he contorts his body amazingly as he delivers the slapstick humour in a brilliantly visual fashion. Onscreen, he and Nathan Lane make for a tremendous comedy team.

The movie also has a Tim Burton-like look to it; there is a distorted (as in alternately distended and extended), cartoon-ish feel to some of the sets, some camera angles and certain action sequences. The humour is not Tim Burton-like, however. It’s much more direct. It makes no effort at subtlety. That may be why it works so well.

Mousehunt was the first full length movie directed by Gore Verbinski, best known now for his Pirates of the Caribbean movies. He has also directed The Mexican (2001) and The Weather Man (2005). Though quite different movies (especially Weather Man) it strikes me that humour is a key element running through his films and of those he experiments with in the sense that Mousehunt is slapstick, Weather Man satire of a dark variety, and Pirates somewhere between.

Whatever the case, I think it’s safe to say you’ll either love or hate Mousehunt. You have to watch it first, however, to find out which.

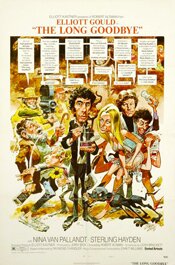

A curious Long Goodbye from Robert Altman

To be honest, I’ve never been a big Robert Altman fan, though increasingly I’m finding his movies more appealing. I think his approach creates the sense in me that I’m listening to a slow-talker and I want to interrupt and say, “Move it along; get to the point.” There’s an improvisational feel to character interaction and part of me want’s it more closely scripted and edited.

In The Long Goodbye this comes across partly because Altman gives his actors more responsibility to actually act, as he does with Elliott Gould here, and partly because the camera is constantly moving, as if you as a viewer are watching and trying to find a better vantage point. Some shots are through windows; some are even reflections in windows.

It’s intriguing, yet for me a bit irksome — but that’s just a personal, subjective thing. And what is odd about it is that I like this movie nonetheless.

The Long Goodbye (1973)

The Long Goodbye (1973)

Directed by Robert Altman

Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye is a bit like a fast food hamburger. It has beef in it but also has so many other things, and it has been altered to such a degree, that while it resembles a hamburger, it ain’t no hamburger.

In the same way, Altman’s movie is Raymond Chandler’s book, and resembles a film version of that book, but it ain’t Chandler’s book.

But then, you wouldn’t expect Altman to make a movie utterly faithful to its source.

Altman’s movie begins with the question, “What would happen if Marlowe, a character of the 40s and 50s, were to wake up and find himself in the early 70s?” In an interview, he says they referred to it as “Rip Van Marlowe” during the making of the movie. This idea dictates how the movie plays out.

Chandler’s Marlowe began in 1939 with The Big Sleep. His book The Long Goodbye was published in 1953. That is exactly twenty years before Altman’s The Long Goodbye.

Chandler’s Marlowe had been in about six books prior to the 1953 book. In The Long Goodbye, his Marlowe is older and mellower. The novel is a bit more reflective and, in my opinion, weighty. There is less emphasis on the tough guy posturing of the early books; he comes across as a more mature character. In some ways, there is a sense of alternating melancholy and apathy in him.

This may be what suggests the “Rip Van Marlowe” possibility to screenwriter Leigh Brackett and director Altman, or at least what makes this book a possible vehicle for working out that theme. However, there is more to the theme than just the “what if” aspect of a man from 1953 waking up in 1973. One thing that has changed for Marlowe is how people view friendship. The world has a different sense of ethics and morality and it isn’t in sync with his.

The movie opens with Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) literally waking up. The first half of the movie, particularly the first twenty minutes or so, give us such a slovenly, disconnected and half-asleep Marlowe that, the portrayal being so effective, he is incredibly annoying. He speaks under his breath, muttering to himself more than anyone else, even when responding to others around him. He’s almost completely unengaged with his world.

He shows no animation at all until his friend, Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) shows up at his door. This is where the story’s engine turns over and it gets underway as Terry asks Marlowe to take him to Mexico.

The story makes some major turns from the Chandler book, some for the purposes of condensation and some … Perhaps because they didn’t want to make a movie faithful to its source but one that stood on its own legs as unique.

Having re-read the book recently (which is probably why I keep referring back to it), and it being my favourite of the Chandler novels, I can’t say I like the deviations. I found the book had more meaning for me than the movie largely because of those things that have been changed, though I do like the movie on its own merits.

But the book’s ending is much more effective and moving, I think. The movie is very direct – you can’t miss its point. In a way, it’s like Altman believes he has to be direct because people in 1973 are as much asleep as Marlowe was. His conclusion is like a bucket of cold water in the face.

The “asleep” idea recurs through the movie. It’s not just Marlowe who is somnambulant. His neighbours, the young women with their yoga and exercise, appear to be lost in their own world of new age exercise and spirituality. Roger Wade (Sterling Haydon) is lost in his alcohol and self-pity. Everyone is self-absorbed and inward looking and Marlowe is the one person who “wakened” to this contagion of social sleepwalking.

Marlowe “wakes up” because something has wakened him: the death of his friend Terry Lennox. He remains true to his friend, though for all intents and purposes it’s meaningless, isn’t it? (Terry is dead, after all.) Yet Marlowe won’t believe the murder and suicide that are being attributed to his friend.

No one else in the movie is true to anyone or anything. Even Marlowe’s cat abandons him when its favourite food is no longer there. Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell) speaks of how much he loves his girlfriend then strike her horribly for no reason. Roger Wade hits his wife when he is drunk.

Throughout the movie, as Marlowe makes his way, he sees a world of self-interest and no loyalty, making him an anachronism. When asked why he would try to clear the name of Terry Lennox, he hears variations of, “What’s it matter? He’s dead.”

The ending aside, this is probably the greatest deviation from the novel. In the book, respect and loyalty keep appearing – Marlowe is hired for his; the gangsters in the book (unlike the Marty Augustine character) respect Marlowe for his loyalty. Even some of the cops do. He is sought out and hired because it’s reported in the newspapers that he was picked up by the police for questioning and wouldn’t talk.

So the difference in the endings becomes a bit curious. Is it simply a more overt, can’t-miss-that meaning concerning betrayal of a friendship or is it also suggesting that Marlowe, too, is becoming part of that amoral culture of self-centeredness?

I’m not really sure. But I do know this is a curious movie Robert Altman has given us.

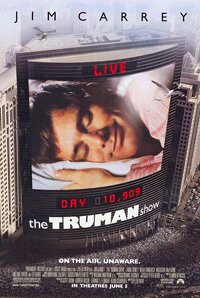

20 Movies: The Truman Show (1998)

An innocent abroad in a less-than-innocent world is a standard story template. It has been used over and over. Decades ago I read Robert Heinlein’s A Stranger in a Strange Land. That was one take on the innocent story. Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, with his main character of Billy Pilgrim, was another.

An innocent abroad in a less-than-innocent world is a standard story template. It has been used over and over. Decades ago I read Robert Heinlein’s A Stranger in a Strange Land. That was one take on the innocent story. Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, with his main character of Billy Pilgrim, was another.

It shows up in movies frequently as well, such as The Truman Show. When it is used, it is often with a satirical purpose. Through the innocent’s eyes, we see how the world really is (or how the author or filmmaker thinks it really is). It’s usually comic, at least to some degree.

But the satire isn’t just intended to illustrate what is wrong with the world. It is also to illustrate what could be right and how we’ve gone off track from pursuing it.

That is really what is at the heart of The Truman Show. It isn’t about the misguided nature of television and its audiences, though it is that in part. And it’s not simply about the hazards of over-the-top commercialism, though it’s about that too.

The story of the innocent is really about what the point of our lives is and what we could be doing with them.

Truman’s story is about a man who wants more. Not more “stuff,” but more meaning. Yes, his life is comfortable. But for Truman, that’s not enough. He wants to know, “What else is out there?”

The Truman Show (1998)

directed by Peter Weir

directed by Peter Weir

“You never had a camera in my head.”

Those words, I think, capture the essence of The Truman Show best. There’s much in the world that can be controlled, but controlling what someone thinks and, maybe more importantly, feels is not so easy.

For me, this is one of the best movies of the 1990’s, and one of my favourite movies, period. Now, with the recent release of it in a special edition, I have the DVD I had been wanting – better image, informative features. (Note: this review was written in 2005 and refers to the Special Collector’s Edition DVD.)

Slightly preceding the current glut of reality TV shows, the film’s concept seems simple enough, though perhaps less clever now than when it first appeared, before our reality TV world.

While the concept may seem simple – a movie about a guy whose entire life is broadcast live on television – imagine how you would execute that and make it interesting. It comes across more like a clever notion on paper, but the kind of thing that could lead you into a cinematic fiasco.

While the concept may seem simple – a movie about a guy whose entire life is broadcast live on television – imagine how you would execute that and make it interesting. It comes across more like a clever notion on paper, but the kind of thing that could lead you into a cinematic fiasco.

But between Andrew Niccols’ script, Peter Weir’s direction and some great casting, it works brilliantly.

Jim Carrey is Truman Burbank. His life , from birth, has been broadcast live to the world (unbeknownst to him). He lives in a town called Seahaven – always has, he’s never left – but what he doesn’t know is Seahaven is a television set in California, not a town on the Florida coast. He lives in a not-quite-perfectly controlled world.

“We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented,” says Christoff (Ed Harris), the show’s creator and mastermind.

“We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented,” says Christoff (Ed Harris), the show’s creator and mastermind.

But as much as Christoff controls Truman’s world, he can’t control everything – including Truman.

There are small errors in Truman’s world and they might go unnoticed by him except the life scripted for him is not the one he would live. The more the show’s creator, actors and crew try to steer Truman and keep him on script, the more he resists.

And so Truman embarks on discovering his world, though that’s not his initial motivation.

As mentioned in the special features, Peter Weir made one change to the script that was bang on the money. Originally set in New York, and a darker film, Weir understood that for people to watch such a show (not the movie, but in the script’s world, The Truman Show), it would need to be lighter, more comforting.

So the movie is set in Seahaven, a somewhat heightened reality. It’s roots are more in the world of 1950’s television than the real world, though not to such an extent that it lacks credibility.

Another great notion in the film’s making was the casting of Carrey. He is perfect as Truman. Charismatic and affable, he brings the right amount of innocence to the role of Truman. It might not have worked in another movie, but in the world of The Truman Show it hits the mark.

I also like that there are several ways of seeing The Truman Show. There is the obvious satire on television culture and the issue of personal freedom.

(I like the irony of Christoff “a very private man” being the architect of a very public life – Truman’s.)

Another way of seeing the film, however, is as a fable of a child leaving home.

Christoff is an obvious father figure and Truman is clearly a young man trying his damnedest to leave and find his own life – but not the one Christoff dreams for him (rather like a parent trying to impose his vision on his child.)

In fact, however you view the film, it’s essentially a fable. Perhaps this is why I like the movie so much – I’ve a weakness for these types of films when they are well done.

In fact, however you view the film, it’s essentially a fable. Perhaps this is why I like the movie so much – I’ve a weakness for these types of films when they are well done.

Weakness or not, I consider this one of the best films of the last decade or so. It’s also one I think will continue to be watched over the years as it captures, quite succinctly and in an engaging fashion, something in the nature of freedom that is deeply woven into the human fabric. The film’s ending captures an archetypal, mythic moment and it’s one that resonates. I can’t recommend this one highly enough.

The Truman Show (the trailer)

Links:

- The Truman Show – DVD, HD, etc. on Amazon.com (U.S.)

- The Truman Show – DVD, HD, etc. on Amazon.ca (Canada)

This cockeyed caravan: Preston Sturges defends fluff

I watched Sullivan’s Travels (1941) yet again last night because, as the main character John L. Lloyd ‘Sully’ Sullivan (Joel McCrea) says:

“There’s a lot to be said for making people laugh. Did you know that’s all some people have? It isn’t much, but it’s better than nothing in this cockeyed caravan.”

The words, of course, are from Preston Sturges, writer and director of the movie. This movie is, for me, the best of Sturges — though it’s really hard to say one is better than another when you consider movies like The Lady Eve, The Miracle at Morgan’s Creek and others.

If you’ve ever seen the Coen Brothers’ O Brother, Where Art Thou? you may be interested in knowing Sullivan’s Travels is where that title came from. It’s the movie Sullivan, a Hollywood director of light, comedic fluff, a man with a well-to-do, somewhat privileged background, wants to make. It’s to be a serious movie about how tough and awful this life is with, “…Bodies piling up in the street.” It’s to be, “A true canvas of the suffering of humanity!”

As his producers point out, what would he know about it? Realizing the truth in what they say, he sets off to find out, decked out like a tramp (from the wardrobe department) and with only ten cents in his pocket.

Unfortunately for Sullivan, despite his best efforts he keeps ending up in Hollywood.

In the third act, however, when he has finally given up his quest, that’s when he actually stumbles into the “trouble” he’s been trying to discover.

A plot summary does little to communicate why this movie is so good.

To begin with, it’s incredibly funny with the humour finding two sources: visual (slapstick) and verbal (witty dialogue). For slapstick, see the chase scene with the kid driving the rigged up “go-cart.” For dialogue, see the scene near the beginning where Sullivan argues for his idea with the producers (“But with a little sex!”).

While very funny (and a romance to boot, with Veronica Lake), it’s a satire of movie makers, particularly of the Hollywood variety. Some even argue that Sullivan’s Travels is the best movie ever about making movies. I think, however, Sturges’ satire goes beyond movies to culture overall.

His complaint is that comedy, and fluff generally, gets dismissed because, being light and agreeable when well done, it isn’t serious, or what we consider to be serious. A history of comedy at the Oscars gives credence to his complaint. It’s ignored when it comes to the “serious” categories like Best Picture.

I think his argument is two-fold: 1) audiences, on the whole, prefer lighter films — comedy, action, etc., and 2) the people who make the serious ones about such topics as homelessness, have no idea, no experience, no real understanding of what they are making a movie about. For one thing, the very people those films are sympathetic to, and that they stand morally side by side with, are the very people they show disrespect to by dismissing the kinds of films they like.

There’s a fabulous speech prior to Sullivan heading out to “learn something about trouble,” meaning homelessness. It’s made by Robert Greig as Sullivan’s butler Burroughs. He says he doesn’t think the plan is a good one because Sullivan has no clue about what poverty is: it’s not some romantic condition to be discovered but something virulent to be avoided. I think this is Sturges saying there is often a patronizing, even parasitic element to serious films and the subjects they treat. That’s probably far too extreme a view, but I think there is an element of truth in it. It makes for an interesting question though: can something not truly lived, something only experienced in a kind of vacation mode, meaning briefly, truly be understood? How often do we bring our assumptions about what something is, assumptions that come from a very different perspective, into our assessments and treatments, such as a in a film?

Of course, the movie doesn’t come across as pontificating, as the above makes it sound. It’s great fun, incredibly funny and with a beautiful Veronica Lake, romantic too. And even if the overall sentiment and the closing lines sound a bit cornball to us, I think it’s a legitimate view and never more passionately expressed as in Sullivan’s Travels.

I’ll have to watch the Coen’s O Brother, Where Art Thou? again because I’m now wondering if they were not only agreeing with Sturges and his argument in comedy’s favour but doing so by making Sullivan’s intended movie, one about a serious subject as done by a patronizing, uninformed fool? My guess is yes.

Havana so-so time

I ordered and received two of Sony’s Martini Movies, a series of films they’re releasing with a retro design, ones with sort of an -ish look and feel. The movies were Our Man in Havana and Affair in Trinidad. So last night I watched Havana.

Actually, I kinda, sorta, maybe watched it. I’ll have to watch it again, or at least the ending, because I fell asleep. Not a good sign.

It’s a satirical take on the Cold War with quite absurd goings on and people very serious about them, regardless of the absurdity. It’s based on the novel of the same name by Graham Greene, who did the screenplay. And it’s directed by Carol Reed. In fact, when you see all the names attached to the film, like director and writer and the stars: Alec Guinness, Maureen O’Hara, Burl Ives and Noel Coward, you can’t help but have fairly high expectations.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t quite work. At least not for me. I had two problems going in: 1) I had read the novel, several times, over the years and, 2) I’m not a big fan of satire – for a skit, maybe, but for a 90 minute or so movie, nope.

I was never engaged. Intellectually, I could see the cleverness. But on a visceral level, I was detached. I’m also not sure a movie such as this, predicated on the context of the Cold War, can work very well outside of that context, such as 50 years or so later in a much changed world.

So … this ain’t no The Third Man. And quite apart from comparisons, on its own merits, this is a so-so film. Their are some good moments, certainly some good performances (though some are over-the-top, which sometimes works in a satire), but as a whole, it’s more a bland curiousity than anything else.

On the other hand, I may find Affair in Trindad quite good since my expectations are very low – the opposite of what I had for Our Man in Havana. Affair sounds as if it’s yet another effort to recapture the essence of Gilda, and that kind of effort fails more often than it succeeds. But we’ll see!

(Yes, my headline is lame. But I’m rushed!)

The Frank Oz comedies

I’ve always liked the comedies of Frank Oz. In fact, I would say that of the films I watch repeatedly, Frank Oz comedies are among the ones I most watch over and over. In a sense, they are a kind of cinematic comfort food. I always enjoy them and I always feel good after having watched them.

His comedies are a bit deceptive. They seem too nice (whatever that means). They seem perhaps too slick, or too something, because they have a pleasant Hollywood gloss to them, which gives them a feeling of unreality.

His comedies are a bit deceptive. They seem too nice (whatever that means). They seem perhaps too slick, or too something, because they have a pleasant Hollywood gloss to them, which gives them a feeling of unreality.

But that’s really why they work the way they do. They aren’t realistic and they aren’t intended to be. They’re movies about interesting, and funny, characters in absurd situations.

What I like most about his comedies, however, is that they are funny without being mean-spirited, as many comedies tend to be. It isn’t the humour of a misanthrope but rather the humour of someone who finds life and people to be wonderful, but also wonderfully ridiculous.

Still, there is a certain (if minimal) element of darkness, even anger in them, but it is kept in abeyance. It’s never allowed to overwhelm the films; it simply serves as a root element from which to spring and inform the comedy. (An example would be In & Out, with intolerance at its core, or the satire of The Stepford Wives – not the best Oz film but certainly better than some gave it credit for.)

Ultimately, Frank Oz comedies are delightful confections that seem to laugh at us while loving us, and loving us especially for those things that make Oz laugh.

Comedies directed by Frank Oz (a partial list):

- Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (1988)

- What About Bob? (1991)

- In & Out (1997)

- Bowfinger (1999)

- The Stepford Wives (2004)

- Death at a Funeral (2007)

(Of the above, I think my favourite may be Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, which I’ve watched so many times I’ve lost count. I can’t believe I’ve never written about it.)