The movie The Shawshank Redemption is a lot like one of its main characters, Andy Dufresne. It’s something of a mystery. Popularity alone has made it a classic, but what does it do right? With so many cinematic elements being quite good but far from standout, how is it this movie resonates the way it does?

A curious thriller: So Long at the Fair

Prior to moving out to California and Hollywood, Jean Simmons was primarily in British films. This makes sense given that she was British. So Long at the Fair is one of those movies. Depending on your age and interests, however, you may recall her best as Rear Admiral Norah Satie in Star Trek: The Next Generation (Episode: The Drumhead).

Crawford and Gable and the oddball Strange Cargo

I stumbled upon Strange Cargo last night and rarely has the word “strange” in a title been used so appropriately. This movie is strange indeed. It’s also a pretty good adventure film starring Joan Crawford and Clark Gable (the latter’s previous movie was Gone With the Wind).

Strange Cargo (1940)

Strange Cargo (1940)

Directed by Frank Borzage

Crawford and Gable are two feisty lovers with a stormy relationship. Neither is a person of outstanding character. The storminess was likely easy for both to convey because in reality the pair, who had a prior relationship, detested one another.

In the movie, Crawford is essentially a hooker (though Hollywood censorship of the period means this is only vaguely suggested). Gable is a nasty, self-centered rogue who manages to be charming at the same time.

We find them on Devil’s Island (French Guiana) where they get mixed up with a group of convicts in an escape attempt. The majority of the movie is the struggles and conflicts of this rag tag bunch as they make their way through the jungle and swamps of the island and then on board a small ship as they try to get away.

Fine enough, and a pretty de rigueur setting for an adventure of the period. But there is an element in the movie that makes it anything but de rigueur. That element is the character of Cambreau, played by Ian Hunter. He appears mysteriously and joins the convicts in their escape but he is not your usual prisoner.

Cambreau is a Christ-like figure that steers the movie into religious allegory and allows the film to meditate on subjects like God, morality, ethics and honour. While this may not sound appealing (and yes, occasionally it is a little heavy-handed), the mysterious quality Hunter’s Cambreau figure brings adds to the adventure.

Gable, by the way, objected to this aspect of the movie. He thought it would prompt audiences to stay away. In his opinion, people expected love and sex in a Crawford-Gable movie.

Both Crawford and Gable are wonderful in the movie, particularly Crawford as the slatternly Julie. I read somewhere that Crawford was quite proud of the way she put her “star” image aside and portrayed the character. I noticed how in many scenes she adds small, subtle touches to communicate the character’s “low rent” status, such as one scene where it is in how she sits (not what my mother would have called “lady-like”.)

She also went without makeup or false eyelashes and her costume, essentially two dresses, was from a bargain boutique.

Gable is equally unglamorous in his appearance, wearing torn clothes and growing increasingly unshaven as the movie progresses. In fact, the movie appears to make a concerted effort to ensure both its stars are unstar-like, visually.

The end result is a movie that is peculiar yet compelling, partly due to its oddness. The Cambreau character, while bringing in the religious element, also adds mystery to the overall adventure as no one ever quite knows who he is.

On the other hand, some scenes aren’t subtle in communicating the Christ figure aspect, such as the scene near the end when Cambreau is in the stormy waters with his arms out, as if on a cross.

Yes, Strange Cargo is an odd movie. But it’s worth seeing at least once, especially if you’re a Gable or Crawford fan.

An aside … According to Warren Harris in Clark Gable: A Biography, this movie was made at a time when “Joan Crawford, whose box-office popularity had sunk an all-time low, had talked L.B. Mayer into teaming them (Gable and Crawford) for the first time since the 1936 Love On the Run, which was also Crawford’s last hit.”

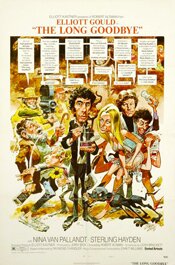

A curious Long Goodbye from Robert Altman

To be honest, I’ve never been a big Robert Altman fan, though increasingly I’m finding his movies more appealing. I think his approach creates the sense in me that I’m listening to a slow-talker and I want to interrupt and say, “Move it along; get to the point.” There’s an improvisational feel to character interaction and part of me want’s it more closely scripted and edited.

In The Long Goodbye this comes across partly because Altman gives his actors more responsibility to actually act, as he does with Elliott Gould here, and partly because the camera is constantly moving, as if you as a viewer are watching and trying to find a better vantage point. Some shots are through windows; some are even reflections in windows.

It’s intriguing, yet for me a bit irksome — but that’s just a personal, subjective thing. And what is odd about it is that I like this movie nonetheless.

The Long Goodbye (1973)

The Long Goodbye (1973)

Directed by Robert Altman

Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye is a bit like a fast food hamburger. It has beef in it but also has so many other things, and it has been altered to such a degree, that while it resembles a hamburger, it ain’t no hamburger.

In the same way, Altman’s movie is Raymond Chandler’s book, and resembles a film version of that book, but it ain’t Chandler’s book.

But then, you wouldn’t expect Altman to make a movie utterly faithful to its source.

Altman’s movie begins with the question, “What would happen if Marlowe, a character of the 40s and 50s, were to wake up and find himself in the early 70s?” In an interview, he says they referred to it as “Rip Van Marlowe” during the making of the movie. This idea dictates how the movie plays out.

Chandler’s Marlowe began in 1939 with The Big Sleep. His book The Long Goodbye was published in 1953. That is exactly twenty years before Altman’s The Long Goodbye.

Chandler’s Marlowe had been in about six books prior to the 1953 book. In The Long Goodbye, his Marlowe is older and mellower. The novel is a bit more reflective and, in my opinion, weighty. There is less emphasis on the tough guy posturing of the early books; he comes across as a more mature character. In some ways, there is a sense of alternating melancholy and apathy in him.

This may be what suggests the “Rip Van Marlowe” possibility to screenwriter Leigh Brackett and director Altman, or at least what makes this book a possible vehicle for working out that theme. However, there is more to the theme than just the “what if” aspect of a man from 1953 waking up in 1973. One thing that has changed for Marlowe is how people view friendship. The world has a different sense of ethics and morality and it isn’t in sync with his.

The movie opens with Philip Marlowe (Elliott Gould) literally waking up. The first half of the movie, particularly the first twenty minutes or so, give us such a slovenly, disconnected and half-asleep Marlowe that, the portrayal being so effective, he is incredibly annoying. He speaks under his breath, muttering to himself more than anyone else, even when responding to others around him. He’s almost completely unengaged with his world.

He shows no animation at all until his friend, Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton) shows up at his door. This is where the story’s engine turns over and it gets underway as Terry asks Marlowe to take him to Mexico.

The story makes some major turns from the Chandler book, some for the purposes of condensation and some … Perhaps because they didn’t want to make a movie faithful to its source but one that stood on its own legs as unique.

Having re-read the book recently (which is probably why I keep referring back to it), and it being my favourite of the Chandler novels, I can’t say I like the deviations. I found the book had more meaning for me than the movie largely because of those things that have been changed, though I do like the movie on its own merits.

But the book’s ending is much more effective and moving, I think. The movie is very direct – you can’t miss its point. In a way, it’s like Altman believes he has to be direct because people in 1973 are as much asleep as Marlowe was. His conclusion is like a bucket of cold water in the face.

The “asleep” idea recurs through the movie. It’s not just Marlowe who is somnambulant. His neighbours, the young women with their yoga and exercise, appear to be lost in their own world of new age exercise and spirituality. Roger Wade (Sterling Haydon) is lost in his alcohol and self-pity. Everyone is self-absorbed and inward looking and Marlowe is the one person who “wakened” to this contagion of social sleepwalking.

Marlowe “wakes up” because something has wakened him: the death of his friend Terry Lennox. He remains true to his friend, though for all intents and purposes it’s meaningless, isn’t it? (Terry is dead, after all.) Yet Marlowe won’t believe the murder and suicide that are being attributed to his friend.

No one else in the movie is true to anyone or anything. Even Marlowe’s cat abandons him when its favourite food is no longer there. Marty Augustine (Mark Rydell) speaks of how much he loves his girlfriend then strike her horribly for no reason. Roger Wade hits his wife when he is drunk.

Throughout the movie, as Marlowe makes his way, he sees a world of self-interest and no loyalty, making him an anachronism. When asked why he would try to clear the name of Terry Lennox, he hears variations of, “What’s it matter? He’s dead.”

The ending aside, this is probably the greatest deviation from the novel. In the book, respect and loyalty keep appearing – Marlowe is hired for his; the gangsters in the book (unlike the Marty Augustine character) respect Marlowe for his loyalty. Even some of the cops do. He is sought out and hired because it’s reported in the newspapers that he was picked up by the police for questioning and wouldn’t talk.

So the difference in the endings becomes a bit curious. Is it simply a more overt, can’t-miss-that meaning concerning betrayal of a friendship or is it also suggesting that Marlowe, too, is becoming part of that amoral culture of self-centeredness?

I’m not really sure. But I do know this is a curious movie Robert Altman has given us.

Chess games and submarine movies

You might think that movies set on submarines are relatively rare. They are — relatively. But as a quick search online will show you (as it just showed me), there are actually quite a few of them. (Das Boot and Crimson Tide come to mind.) Relative to other movies, they may be rare. But there are quite a few of them nonetheless.

This leads me to the two movies I wanted to bring up: Run Silent, Run Deep (1958) and The Hunt for Red October (1990). I don’t know what the correct term for describing them would be — suspense, thriller, action? I lean toward suspense but what makes them compelling is a phrase Sean Connery’s character, Marko Ramius, uses in Red October: chess game.

This leads me to the two movies I wanted to bring up: Run Silent, Run Deep (1958) and The Hunt for Red October (1990). I don’t know what the correct term for describing them would be — suspense, thriller, action? I lean toward suspense but what makes them compelling is a phrase Sean Connery’s character, Marko Ramius, uses in Red October: chess game.

There is more actual “action,” as in torpedoes and so on, in Run Silent, Run Deep, but neither film has a great deal of it. It’s the drama of the situations and, again in both films, the mystery surrounding a lead character’s motives, Clark Gable’s in Run Silent and Sean Connery’s in Red October.

Both movies get more physically and visually dramatic with action in their final acts but for the most part these chess games are mysteries rather suspense thrillers, though both are suspenseful and, I suppose, thrilling.

However they are described, I like both movies quite a lot and have watched both many times. They are well worth seeing more than once ….

Run Silent, Run Deep (1958)

I saw an interview with the actor Laurence Fishburne the other day in which he was speaking of various influences when he was young. At one point, he brought up the movie Run Silent, Run Deep and Clark Gable. What struck him in the movie was Gable’s gravitas. I immediately thought, “Yes, that is the perfect word for it.” (Read more)

The Hunt for Red October (1990)

In the class of movies known as action-adventure, The Hunt for Red October stands out as one of the best and as one of the strangest because the action is relatively minimal and doesn’t play a huge role in generating the film’s suspense and tension. (Read more)

Film noir means B-movies like The Hot Spot

The Final Day of For the Love of Film (Noir) — Please or use the button on the right. If you’ve considered it but have put it off, now is the time. If you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down the page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

Best known as an actor, Dennis Hopper also directed movies — eight, I believe, including the well known Easy Rider. Hopper never set the world alight as a director, but in 1990 he made a pretty good film noir called The Hot Spot. (The movie’s poster does a bit of over-selling with the words, “Film noir like you’ve never seen.”)

It’s a good example of a certain kind of neo-noir. As a genre, noir returns again and again because it tells a certain kind of story in a certain way. In The Hot Spot, you sense this is why Hopper is doing a film noir. On the other hand, you can see a neo-noir like the Coens’ The Man Who Wasn’t There and view a film that chooses the genre for the same reason but also for its style — in the Coen’s case, it’s a puzzling mix of homage and parody.

The Hot Spot is really just about its story: corruption. It’s not a great movie; it’s average. Still, it’s engaging and in some ways more true to noir for that reason (and what I assume was likely a comparatively small budget). It’s made as a B-movie and looks and feels like a B-movie. Here’s the review I wrote of it about ten or so years ago. ( There may be spoilers ahead, explicit and implicit.)

The Hot Spot (1990)

Directed by Dennis Hopper

“I found my level. And I’m livin’ it.”

This is a pretty good film noir from 1990 directed by Dennis Hopper. For some reason The Hot Spot seems to dwell in the undeserved province of obscurity. Yet it has all the noir elements, presents them well, and resolves itself in a fashion that would please Alfred Hitchcock.

It stars Don Johnson as a drifter – we never learn much about who he is, his past, or much background to support his motivation. But this doesn’t matter; in fact, it actually works for the film since it helps create a sense of mystery.

It also leaves you never quite sure about whether he’s a good guy or a bad guy.

He wanders into a sweltering “nothing-ever-happens-here” small town to get his car repaired then takes a job as a car salesmen as he waits. While waiting, he also checks out the lay of the land. What he finds is a dull town anxious for something, anything, to happen.

It’s the tedium of the town that has generated its odor of corruption and you can’t help feeling that the catalyst behind all the avarice and moral decay is simply boredom.

While in the town, Johnson’s character sees what appears to be an easy opportunity to rob the local bank and, seeing this, he immediately begins planning to do so. Script, acting and direction work well here as it is never explicitly stated that this is what he is planning; it’s communicated through selected shots, angles, and facial expressions. In fact, while you suspect this may be what he is up to you are never quite sure.

The other two principle characters in the film are Virginia Madsen as a slatternly, greedy wife and Jennifer Connelly as a young, innocent woman who is being blackmailed (despite the apparent contradiction in that).

Compounding the problems for Johnson’s character are the relationships he forms with these women. It reflects the conflict within Johnson’s character between doing what is right and doing what is wrong: in Madsen, he recognizes a similarly corrupt soul and while he is attracted to her he is also repelled. It is as if he sees himself in her and it generates a kind of self-contempt that he expresses through his contempt of her.

In Connelly’s character, he sees what he has lost and wants to get back: a sense of innocence and goodness. Through her, he sees the man he would like to be (as opposed to Madsen’s character which shows him what he feels he is and wants to leave behind). This is the essential conflict in the story, a moral one. It drives the story. Which way will Johnson’s character ultimately go?

The story and Hopper’s directing lay a seamy, sultry tone over the entire film. It is sexy in a sluttish way; an air of corruption hangs over everything. With the exception of Connelly’s character, everyone is an aspect of moral decay. Everyone is motivated by base interests, even Johnson’s character though he is the only one struggling with it.

While not stylish in the way the Coen’s The Man Who Wasn’t There is, The Hot Spot is probably a better example of noir. (This doesn’t mean it is a better movie; just a better example.) It is better in the sense that where the noir feeling in the Coen’s film is communicated through angles, lighting and other technical and stylistic elements, in Hopper’s film it is the story, characters and performance that make this noir. It’s not a brilliant film by any means, but it is damn good. Where a movie like The Man Who Wasn’t There looks like film noir, The Hot Spot feels noir – and that is what noir is. Feeling. Mood.

If I have a quibble with the movie it would be it’s length. It probably should have trimmed about 20 or 30 minutes. After all, most of the film noirs that originated the genre ran between 70 and 90 minutes.

(By the way, there are no points for the movie’s title. It’s pretty unimaginative. It’s also the same title I Wake Up Screaming would have had if the studios had had their way. Fortunately, the actors objected and they went with the original title.)

Chinatown and the self-aware noir

It’s Day 5 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. And if you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down this page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material! (Also see today’s Blogathon Notes.)

One of the few things I’m certain about with the movies that started this whole film noir business, movies from the forties and fifties like The Big Heat, Double Indemnity, or Gilda, is that they were not aware of themselves as being in a genre called film noir. They might have thought of themselves as B-movies, crime movies or pulp, but not film noir. Categorization like that always comes after the fact.

But once an approach or style is identified, like film noir, subsequent movies taking that approach are self-aware. They see themselves as film noir and inevitably try to replicate the approach. They may try to do much more, but they can’t be made the same way as the original film noirs were. Awareness affects what is being created.

Just as you can’t see the same movie twice (not in the same way), you can’t make the same kind of movie twice. But you can come damn close!

Chinatown (1974)

Directed by Roman Polanski

Chinatown, a wonderful movie, is an example of what a script can do for a film.

It’s like finding the right music at a party. Someone feels compelled to dance, then another and another. Soon, everyone’s up dancing. And dancing well.

In Chinatown, just about every artist is dancing their damnedest because the script has pulled them onto the floor. Director, actors, lighting people, costume designers … they’re all performing at their highest level.

It’s Robert Towne’s script that has done this.

One of Roman Polanski’s great talents is creating mood and few films do it so well and so quickly as the opening of Chinatown. I can’t think of many movies I would watch simply to see the opening credits but the look and the marvellous music of the introductory credit sequence is just so good with its period lettering and sepia tone (which carries through the movie), that you’re hooked even before the movie has presented its opening shot.

Modelling itself on the film noir style (particularly films like Howard Hawks’ movie The Big Sleep), the film’s mystery is created by presenting the story through the eyes of detective Jake Gittes, the Jack Nicholson character. We know what he knows, we’re puzzled by what he’s puzzled by, we’re misled by what misleads him. In fact, just as Bogart was in just about every scene of The Big Sleep, Nicholson is in just about every scene in Chinatown, either as a participant or as an observer.

But the film isn’t dependent on Nicholson. Faye Dunaway is perfectly cast as the enigmatic, and troubled, Evelyn Mulwray. It’s hard to imagine anyone else but Dunaway in that role. The movie is also bolstered by brilliant supporting performances, particularly John Huston as Noah Cross.

I also love the leisurely way the movie unfolds. Unlike the quick cuts and thrumming soundtrack of most current movies, Polanski takes his time. And it works so well. This may be the reason why it works. You’re seduced by the mood, and become involved with the characters, and thus the story.

Chinatown is a great, fascinating movie that illustrates the importance of beginning with a great script.

With the DVD … it’s okay. Not great, could be a lot better, but adequate. It’s largely clean and clear, but certainly not on the pristine level.

This is partly due to it being an older film (1974). For extras, there is really just one (I don’t count trailers as extras).

There is a documentary of sorts. It features interview clips with director Roman Polanski, writer Robert Towne, and producer Robert Evans.

There are some interesting comments, but there is really no depth to it … Par for the course with DVD extras.

(Note: This was written more than 10 years ago. The DVD comments refer to an early DVD release. The movie has since been released in a “special edition” which, I believe, is an improvement.)

The accidental film noir: I Wake Up Screaming

It’s Day 2 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to (or use the button on the right). Today I have a quickly scribbled, un-proofed, un-thought through look at the movie I watched last night. The studio considered calling it Hot Spot but, according to the DVD I have, the actors insisted on them using the original name, which is …

I Wake Up Screaming (1941)

Directed by H. Bruce Humberstone

As I watched I Wake Up Screaming last night I had two thoughts running concurrently. First, this should not be a good movie. Second, somehow it manages to be a good movie. How does that happen?

I’m not sure. I think it lies partly in Betty Grable, whose performance is a level above the other main actors in the movie.

It’s also in the characterization of Ed Cornell, played by Laird Cregar, who seems a cross between Vincent Price (in the slightly effeminate voice and its cadence) and possibly a low rent version of George Sand. (I mean vocally, nothing else, and not much there either. But there seems to be something vaguely Sand-ish in the voice.)

Cregar’s Cornell is creepy, to say the least, and that makes the movie compelling. Though the film’s mystery may be obvious, it doesn’t matter. The creepiness keeps us fascinated in a “slowing down to view the accident” kind of way. Cregar’s character isn’t the only one that gives us the willies.

Elisha Cook Jr.’s Harry is equally troubling. Soft-spoken and gentle, his focus and attentiveness to Grable’s Jill Lynn leaves us feeling something isn’t right about him. He’s stalker material.

Much of what makes the movie watchable is in the script. The bad guys in this movie – and there are a lot of them – are not villains so much in the commitment of crimes regard, as in their psychology. In fact, most of them have stalker-like personalities or variants of it.

They are all focused in some way on Vicky Lynn, played by Carole Landis. They want to either possess her, use her, or both. And she, being ambitious, is happy to permit it as she uses them. Thus, in a sense, she invites what follows from it.

Into this morass of twisted personalities come Victor Mature as Frankie, a kind of nice if goofy sports promoter (who find himself accused of murder) and Vicky’s sister, Grable’s Jill Lynn.

Frankie and Jill are the normal ones (for lack of a better word) and also the ones who suffer the consequences of a world populated by twisted personalities.

Visually, the movie delivers the noir goods but that may be less an aesthetic decision as a kneejerk response to making a crime movie in the forties. Crime equals scenes of darkness and shadow, ergo scenes of darkness and shadow. I get the sense director H. Bruce Humberstone was a paint-by-numbers kind of director, though that may be unfair to him. But that is how it strikes me.

Still, by accident or design, the movie looks good as a noir. It has a low budget feel and some very nice shots, especially near the end where we see Mature looking down at Harry snoozing at the front desk.

Overall, then, I Wake Up Screaming strikes me as an accidental noir. It discovers a noir world in the script it brings to the screen and in the kind of kneejerk response of how it visually portrays that script.

Much of what happens on screen is highly melodramatic and it would be too much were it not for the material driving it, Laird’s unsettling Cornell, and Grable’s much better anchored performance as Jill. Victor Mature looks great as a noir character, especially in the interrogation scenes, but he is often well over-the-top. Also, for about two thirds of the movie, once outside the interrogation room (and often within it) he plays a goofy kind of guy without a care in the world. It’s deliberate, in part, as it’s an aspect of the character. But it just seems too much.

And having gone on with all these negative comments about the movie, I still have to say I liked it quite a bit. However, it feels to me it’s a good movie through dumb luck; a film noir by accident.

How Chandler’s Marlowe is like Hamlet

Inexplicably, after what seems a kind of cinematic hiatus, I’m watching a bevy of older films and, to the dismay of some, rambling on paper (or screen, to be more accurate) my dimly lit opinions of what I’m seeing. I seem to be bouncing back and forth between noir and romantic comedies. The only thing I can venture as at least an explanation in part is this: I find watching movies relaxing, even meditative in some way. I don’t get this watching TV; only movies.

The other day, it was yet another noir …

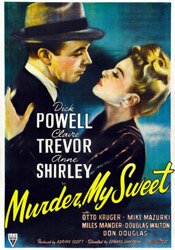

Murder, My Sweet (1944)

Murder, My Sweet (1944)

Directed by Edward Dmytryk

This murder mystery is, for me, itself a mystery in that I cannot fathom why they would change the title of Raymond Chandler’s book, Farewell, My Lovely to the far less subtle, Murder, My Sweet. I know it had something to do with not wanting to confuse the public with lead actor Dick Powell’s previous roles as a kind of song and dance man, but that doesn’t seem a very credible reason to me.

I suppose it’s not very important in the larger scheme of things, but it makes me shake my head. As for the movie …

When you go over reviews of this movie, as well as other movies based on Chandler’s books, you see one topic continually pop up: who was the best Philip Marlowe? It is probably not surprising to find there is not a great deal of consensus.

It strikes me that Marlowe is a kind of variation on Hamlet in that everyone has to play him, or a variation on him, and we decide who does it well, who doesn’t, and who’s Marlowe we buy into. On the DVD case cover, it tells us Dick Powell, who plays Marlowe in Murder, My Sweet, was author Raymond Chandler’s favourite. Of course, others have different opinions. Bogie comes to mind.

For many people Humphrey Bogart (The Big Sleep) is the Philip Marlowe. But just today I came across a review where the writer was claiming the best Marlowe was Robert Mitchum in 1975’s Farewell, My Lovely.

For many people Humphrey Bogart (The Big Sleep) is the Philip Marlowe. But just today I came across a review where the writer was claiming the best Marlowe was Robert Mitchum in 1975’s Farewell, My Lovely.

I admit that when I first saw Murder, My Sweet a few years ago Powell bothered me, but that had less to do with his performance than the fact I had Bogie so drilled into my head, from The Big Sleep but also similar characters, like Sam Spade from the The Maltese Falcon.

But I watched Murder, My Sweet again last night and I liked Powell much more. His gestures and speech fit the character nicely and he seems very natural as Marlowe. And the more I think about it, the more I think, “Yes, I like Powell’s Marlowe.” (That’s sort of like saying, “I like Plummer’s Hamlet.”)

As for the movie as a movie … It has a lot of what you would expect from a film of this kind: a lot of uncertainty as characters appear to be good, then bad, then good again, and then bad once more. Marlowe seems to think one thing then it’s shown he was only pretending, although a later scene shows he actually does think and feel that way.

In other words, the movie twists quite a bit and in many cases the twists are arbitrary for the sake of being a twist and to sustain the mood. But they don’t make a lot of sense. Yet in a film noir, you can often get away with that because the movie is less about plot and more about atmosphere, characters, character relationships … and lighting and camera focus.

In other words, the movie twists quite a bit and in many cases the twists are arbitrary for the sake of being a twist and to sustain the mood. But they don’t make a lot of sense. Yet in a film noir, you can often get away with that because the movie is less about plot and more about atmosphere, characters, character relationships … and lighting and camera focus.

I’ve read the book this movie is based on but don’t recall it, so I can only assume the movie stays roughly true to it and, if that’s he case, the filmmakers can thank Chandler for writing them an opening that is a nicely baited hook.

Told almost entirely in flashback by Marlowe, it begins with him in a police station being questioned and telling his story. That wouldn’t be much except we’re shown that he can’t see; his eyes are completely bandaged up. So as he’s is grilled and finally starts telling his story, we’re already hooked on the mystery of what happened to his eyes even before we’ve had an inkling of the real mystery.

Being film noir, we also get a femme fatale. Claire Trevor is Mrs. Helen Grayle, aka Velma. Director Edward Dmytryk introduces her to us legs first, underlining the character’s sexual nature and involvement with the story. But the there is also Anne Shirley as Ann Grayle, step-daughter and enemy of the second Mrs. Grayle (Velma). It’s easy to see why.

Being film noir, we also get a femme fatale. Claire Trevor is Mrs. Helen Grayle, aka Velma. Director Edward Dmytryk introduces her to us legs first, underlining the character’s sexual nature and involvement with the story. But the there is also Anne Shirley as Ann Grayle, step-daughter and enemy of the second Mrs. Grayle (Velma). It’s easy to see why.

Ann Grayle loves her father (Miles Mander), who is much older than his new wife. He also seems frail by comparison to everyone else in the film, even impotent. And he’s married to a woman who doesn’t appear to cover up what she’s interested in:

Helen Grayle: I find men very attractive.

Philip Marlowe: I imagine they meet you halfway.

But the movie isn’t just about this. It begins with a man named Moose (Mike Mazurki), who is just out of jail and looking for his Velma.

But the movie isn’t just about this. It begins with a man named Moose (Mike Mazurki), who is just out of jail and looking for his Velma.

Chandler books, and movies of this variety, are peppered with characters, most of whom are types, and give the storyline places to go and people to engage with as well as scenes to play out before getting to an end.

I liked how this one plays out. I like Dick Powell as Philip Marlowe and Claire Trevor as a femme fatale. And I’m pretty sure I’ll be watching this one again.