Among the many fascinating and, in this case, amazing things about The Maltese Falcon is that it was the first film for Sydney Greenstreet who was 62 years old at the time. Can you imagine any actor today getting a role, much less starting a career at 62?

Film noir and film preservation

If we actually lived in a film noir world, there would be a certain futility in trying to preserve a movie. What would be the point? Nothing lasts; everything dies. It’s all hopeless … in a film noir world.

If we actually lived in a film noir world, there would be a certain futility in trying to preserve a movie. What would be the point? Nothing lasts; everything dies. It’s all hopeless … in a film noir world.

Fortunately the real world differs considerably from how we choose to see it — be it through the eyes of a Fritz Lang or a Walt Disney. That’s also why I remind you (as if anyone who likes movies needs reminding) that in a little over a week the For The Love of Film (Noir) blogathon gets underway. It runs February 14 to 21 and I’ll be taking part by tossing up a few posts. I suspect I’ll be the blogger least informed on the subject but I sort of like that idea.

There’s a nice opportunity to learn more.

I can say this about what makes this blogathon particularly fascinating to me (apart from the film preservation aspect): I’ll find it intriguing to see what some people consider film noir. Like most genre terms, be they applied to movies or something else, there is an aspect of subjectivity that smudges lines and makes things difficult to grasp the more closely you look at them.

I can think of one movie from 2003 that I think of as noir but I want to watch it again and see if I still think so (I need to get the DVD back from a friend). If I still think of it as noir, I’ll be curious to see if anyone else does.

Another movie I’d like to watch and possibly re-do what I wrote a few years ago is Kiss Me Deadly, a movie I absolutely hated when I first watched it. Because I reacted so strongly the first time, in the negative sense, I find it difficult to persuade myself to re-watch. I hope I can because it makes for another interesting question: when cynicism becomes nihilism, is it still film noir or does it become a parody of the genre?

I suppose that depends on how you define noir. Is it mood? Story? Lighting? Direction? Is it just snappy Raymond Chandler-like dialogue and guys wearing fedoras?

I hope we can find out in a little over a week!

Man Hunt and Fritz Lang’s dance with propaganda

There is a strange irony in a movie like Man Hunt and its director Fritz Lang making the film meet the propaganda demands of the period. Those demands explain (I’m speculating) the sudden and out-of-the-blue ending to Man Hunt.

If ever there was a director who knew something about what Hitler and the Nazis meant, it was Fritz Lang, who left Germany and his career there because of them. As it is, he made Man Hunt and within it we see a very cold and brutal portrayal of what the Nazis were and represented.

Man Hunt (1941)

Directed by Fritz Lang

I like going into a movie knowing nothing about it, or next to nothing. That’s how I went into Fritz Lang’s Man Hunt. I knew about Fritz Lang though not a great deal. Let’s say I was aware of him and how he’s spoken of as a director.

Man Hunt fairly quickly lets you know what it is about, though in a deceptive way. It begins with a big game hunter lying in the grass, up in an elevated and hidden position, setting his rifle’s sights for a shot. Curiously, the scene intercuts with a German army officer, a Nazi, walking in what seems the same area.

Then we see what the hunter is aiming at: Hitler. We see he has the shot but, surprisingly, he doesn’t take it. He’s satisfied with knowing he could take it, and relaxes. Then he pauses, seems to reconsider, and puts a cartridge in the gun and re-aims.

He appears to have decided to take the shot and kill Hitler. He seems about to when the German soldier the scene had been intercutting with sets upon him. He’s stopped and taken prisoner.

We next see him, apparently having been beaten, taken to Major Quive-Smith, played by George Sanders. Now, we get the last few elements the story needs to really get going. We already know the time period, around the Second World War. It gets more specific now: it’s 1939, just before the war begins and world politics are sensitive to say the least.

What Major Quive-Smith wants from the game hunter, the well-known Captain Alan Thorndike played by Walter Pigeon, is a signed confession that he was trying to assassinate Hitler and was working for the British government.

To cut to the chase (no pun intended), Thorndike is tortured, yet continues to refuse. Finally, the Major takes him out and has him thrown from a cliff, murdered by the Nazis. He doesn’t die, however, and manages an escape and the chase is on. The big game hunter becomes the hunted and it is the Nazis, headed by Major Quive-Smith, and a darkly quiet and sinister looking John Carradine (“Mr. Jones”), who are hunting him.

The movie is about this hunt and, once Thorndike meets the young cockney woman Jerry, played by Joan Bennett, about a relationship that is somewhere between platonic and romantic. (Bennett plays Jerry with an accent that may be a tad overdone.)

The movie is about this hunt and, once Thorndike meets the young cockney woman Jerry, played by Joan Bennett, about a relationship that is somewhere between platonic and romantic. (Bennett plays Jerry with an accent that may be a tad overdone.)

It’s a very good, quick paced movie that pulls you in immediately with its tantalizing opening. As far as suspense goes, Lang knows his business. Along with the quick pace, there are some wonderful shots.

I wrote about Ugetsu recently and director Kenji Mizoguchi’s penchant for a moving camera shot, like his scrolling shot. In Man Hunt, Fritz Lang also uses this kind of thing (though not to the degree Mizoguchi does). The film opens with a moving camera shot that softly dissolves into another moving shot that, in turn, also dissolves into a moving shot. The effect is of one long moving shot that comes to a rest on Alan Thorndike aiming his rifle at his target, Adolf Hitler.

Throughout the movie you see Lang framing shots in wonderful ways and many of these also involve movement though not of the camera but of the characters.

There is one where a German officer is sitting at a desk and above him there is a large emblem. Initially, you think there is something wrong with the framing because it seems unbalanced – the space between the officer and emblem is too great. Then the officer stands and fills the frame and the shot makes sense.

Lang also creates great scenes combining his talent for framing shots with great sets that involve lines, labyrinths and curious designs. Visually, Man Hunt is fun to watch.

In fact, the only sour note would be the ending. On one hand, there is a very darkly Fritz Lang element to the story’s end for one major character, and there is a wonderful scene between Major Quive-Smith and Thorndike.

On the other, there is the abrupt ending with its patriotic trumpeting. It is understandable – the movie is a wartime propaganda product – but jarring.

So about ninety-seven percent of Man Hunt is a tremendous, suspenseful movie from Fritz Lang. It is well worth seeing.

On Amazon:

Film preservation in Dawson City

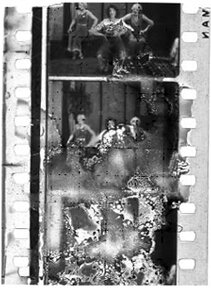

In 1978 a startling discovery elated the small world of film preservationists, restorers, and scholars. A trove of long lost original nitrate copies of silent movies was uncovered at a construction site in Dawson City, Alaska. Among them were long lost films starring Pearl White, Harold Lloyd, Douglas Fairbanks, and Lon Chaney. The permafrost had preserved them for 50 years after they had been tossed into an empty, abandoned swimming pool and covered with fill dirt.

How did these cinema treasures get to Dawson City? The story says a lot about the path of film preservation. Dawson City, it turns out, is at the end of the movie theater print circuit. Prints are usually shipped from theater to theater in an unchanging pattern. A new print starts in a big city like Seattle. From there it might go to Spokane, and then to Bellingham; next on the list might be Fairbanks, then Nome and finally Dawson City.

By the time a print arrives in Dawson City it has been run through a couple dozen grinding projectors by gum chewing teenage projectionists. It has been broken, spliced, cut to insert trailers and re-spliced and re-broken. It has so many scratches the Dawson City audience probably thinks it is always raining in the lower 48.

When a print ends its run in Dawson City it’s not worth shipping back. At first, the local movie theater donated the prints to the library. But in 1929 the library decided they didn’t want a lot of highly flammable nitrate prints in their stacks. They heaved them into an abandoned swimming pool where they were used as fill trash.

Trash: that’s the secret of film preservation. The great find of 1978 happened because somebody was digging a new foundation and unearthed a movie burial ground. The permafrost layer in the fill dirt above the movies had preserved them as good as in a temperature-controlled vault. They were given to the Library of Congress and restored.

Many assumed-lost movies have been found this way. They turn up in Uncle George’s attic or in Grandma’s garage. Movie making has always been a seat-of-the-pants occupation balanced between tight budgets and the rush to make money. Studios rarely kept archive prints. It was just another expense nobody wanted to pay for.

And why bother? The film negative was stored in the lab vault under lock and key and temperature control. That is, if the producer paid the rent and sprinkler pipes didn’t break and flood. Hollywood pros speak the name Roger Mayer with reverence. He was in charge of the lab at MGM and one of the first people to realize the tremendous value of carefully preserved movies. He convinced the studio to let him reprint many old ones on modern film stock. Before celluloid replaced nitrate as the base on which moving pictures were photographed, even carefully stored movies could turn to dust.

Every film student knows the story of Robert Flaherty traversing the Arctic making his famous documentary, Nanook of the North. After a year of shooting, he gathered all the film in his cutting room to edit and lit a cigarette. Poof! In 30 seconds everything was gone (Flaherty went back a second time and reshot the film).

Once missing films are found, the science and art of film restoration takes over. The caisson where most of this happens is an underground labyrinth at the Eastman House of Photography, in Rochester, NY. (There’s no reason it is underground except George Eastman’s old mansion is on top of it). Technicians have special machines for cleaning, lubricating, and printing. Old images are not the only problem. Film shrinks over time and will not fit the sprocket gears of newer machines. Restorers are crafty folks who know secret tricks like wet gate printing and high resolution video manipulation. Sometimes they must restore one frame at a time. They are true alchemists.

The next time you see Marty Scorsese on TV standing at one of those black tie parties announcing a brand new print of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, think of Dawson City, The Eastman House, and all those people who knew enough to read the labels on the cans before cleaning out Grandma’s garage.

(A big thank you goes out to for today’s guest post. You’ll find him over at Movie With Me where I – Bill – am an occasional contributor. Here is how Roberto describes himself at Movie With Me: “Resident Curmudgeon & Film Buff

“As a long time Hollywood producer, I love the internet because there are no rules, no gatekeepers, no stupid executives whose only skill is looking good in a suit. And I love film. The ones that are great, and the ones not-so-great that have moments of inspiration or brilliance. Making a movie is a roll of the dice. Once you have actors and tempers and weather you never know what will happen. The only thing you can be sure of is it will never turn out exactly the way you planned. I salute anyone who tries, and I try to sing the unsung because they too deserve a little glory for attempting the impossible. “

Many, many thanks!)

20 movies: The Big Heat (1953)

Depending on your age, you may remember seeing Glenn Ford in movies and on television. I’m thinking roughly of the 1970’s, perhaps late 60’s. He usually had an avuncular quality. He was a nice, friendly older man. He often played fatherly types. For example, in 1978’s Superman: The Movie he played kindly Pa Kent.

So for us, seeing his work from the 1950s comes as a bit of a shock. The actor we see in movies like The Big Heat is anything but Pa Kent.

It’s hard to know where to begin with The Big Heat. It is about as dark as movies get, and that sort of makes sense since it’s directed by Fritz Lang, a man Roger Ebert refers to as, “… one of the cinema’s great architects of evil.”

How does Pa Kent wind up in a Fritz Lang movie? If you see the domestic scenes in the movie, and the contrast between them and the rest of the film, you’ll see why. Lang explores evil, both its extremes and its subtleties. Ford plays his part perfectly, enunciating both sides convincingly and leaving us wondering just what kind of man this really is.

I’m not sure the review below is quite how I think about the movie today. I want to watch it again and possibly revise it. I’m wondering now if Glenn Ford’s Det. Sgt. Dave Bannion might not be the original Dirty Harry.

The Big Heat

directed by Fritz Lang

Now this is what a noir film should be. Good guys, bad guys, and a lot of dubious ground between them. (Mind you, it’s not a noir film in the strictest sense.)

Perspective is everything, I suppose, and perhaps that is why (for me) noir works best in black and white. It’s how I came to know them when I was younger. This doesn’t mean more recent, colour noir movies don’t work (just look at Chinatown and L.A. Confidential), but black and white just seems more appropriate.

Maybe it’s the sense of shadow and gray that comes across. It reflects the heart of these stories, an uncertain, dangerous world where it’s hard to tell who is on your side, or even what side you’re on.

As in Gilda, the casting of Glenn Ford is perfect. He plays these parts well. He’s the hero, but not so heroic as to be unbelievable. In fact, the type of hero he plays here is the same type Clint Eastwood got so much mileage out of for so long. He’s the ambiguous good guy.

Then there’s Gloria Grahame who gives a wonderful performance as Debby, the gangster’s girl.

But where The Big Heat really excells is in casting Lee Marvin, an actor who gives Robert Mitchum a run for his money as one of the meanest s.o.b.’s to appear on screen.

Marvin’s explosive and sadistic temper come across as so natural you would be afraid to meet him anywhere but on the screen.

In many ways, The Big Heat is a template for certain types of films (though it certainly wasn’t the first to use this pattern). This is a revenge story. But watching it from this point, over 50 years after it was made, it’s easy to forget that some of the set-ups and patterns were not established in the way they are now so, while in some ways they appear to have a certain stale, over-used quality, the truth is they were fresh and even alarming in 1953.

For example, there is the set-up scene where the domestic life of the Ford character is shattered. The scene becomes the catalyst for the character’s later actions. This pattern has been used over and over again since (again, particularly by Eastwood).

Regardless whether it’s perceived as new or cliche, it works. From start to finish The Big Heat holds you and carries you through its dark unwinding. To be perfectly true to the noir genre, Ford’s character is not as corrupt as he should be (though his revenge could be considered a form of corruption, I suppose). But this is quibbling. It certainly has the noir feel and that is far more important. Noir is really about atmosphere; it’s about tone.

This one is highly recommended.

The Woman in the Window – review

Yes, I finally reviewed a movie. And it goes like this:

I’ve had The Woman in the Window (1944) in my “to be watched” pile for a very long time. And this is odd given that I was anxious to watch it. With Fritz Lang directing and the script coming from Nunnally Johnson, I had some fairly high expectations.

I’ve had The Woman in the Window (1944) in my “to be watched” pile for a very long time. And this is odd given that I was anxious to watch it. With Fritz Lang directing and the script coming from Nunnally Johnson, I had some fairly high expectations.

Well, I finally watched it last night and I regret to say it was a disappointment. While it had some good moments and a pretty impressive cast that included Edward G. Robinson, Joan Bennett and Raymond Massey, overall I found it kind of trudged along from scene to scene and, more significantly, suffered from two pretty major story flaws. (Also, for Fritz Lang, who sets a pretty high standard, the directing seemed pretty pedestrian, though it had some moments.)

The first story flaw is Edward G. Robinson’s character who is, depending on the scene, a rather boring, homebody professor, a frightened introvert, a man single-minded, focused and in control, and then a frightened little man. Who in the world was he supposed to be? And who was responsible for this muddled characterization? I find it hard to blame Robinson as I assume this was written into the script. However, shouldn’t the director and actor have voiced some misgivings?

The second flaw for me was the ending. I won’t give it away, though I’m not sure it would matter, but I found it hugely disappointing because it is such a cheap, easy-out trick. It reduces the film to a rather poor installment of, say, The Twilight Zone or Night Gallery, the kind of show that relies on some twist at the end.

I suspect the ending had something to do with the studios. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to find that Lang’s movie ended about two or three minutes before this final version ends, the ending here being something the studio likely insisted on, finding the other too bleak. That’s just a guess but I find it hard to believe Fritz Lang would have wanted this ending.

I suspect the ending had something to do with the studios. I wouldn’t be at all surprised to find that Lang’s movie ended about two or three minutes before this final version ends, the ending here being something the studio likely insisted on, finding the other too bleak. That’s just a guess but I find it hard to believe Fritz Lang would have wanted this ending.

I suppose ultimately the blame falls on Nunnally Johnson for the script. While no one excels in the movie (director, actors etc.), everyone more or less does a competent job. The elements that hurt the movie, and perhaps deflated everyone so they simply did their job and no more, are all in the script.

1 ½ stars out of 4.