Ridley Scott likes his movies big. In 2005, he made one of them — an old school sword-and-sandals epic called Kingdom of Heaven that despite its action scenes and moments of brutal violence, is overall a surprisingly quiet, thoughtful cautionary tale about the hazards of extremes.

A manly Greta Garbo

Garbo talks! Garbo returns! Garbo rules!

And so on.

Greta Garbo was a big deal when she was alive and her star ascendant. It’s difficult to really get a sense for someone’s popularity when it is read about historically and not something lived. How does someone growing up in the Beatles heyday communicate the zeitgeist of the period in a way that gets across the visceral feel?

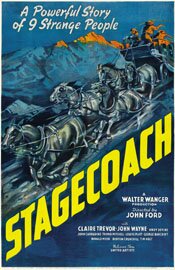

An imposing little Stagecoach from John Ford

When you think of how long it takes to make a movie today, at least a Hollywood movie, it’s quite astonishing to find John Ford cranked out three pretty extraordinary movies in 1939. His “go to” guys in that period were Henry Fonda and John Wayne. (In 1939-1940, he made five films — three with Fonda, two with Wayne.)

The number of movies isn’t the amazing part, though it is notable; what is remarkable is the quality of those films. (The movies are Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home.) For many, that creative glut would be a career. With Ford, some of his best films were still ahead of him.

Stagecoach (1939)

Stagecoach (1939)

Directed by John Ford

For what is essentially a simple western, Stagecoach is a pretty imposing little film. It’s daunting for all the film history associated with it, beginning with the introduction of John Wayne as movie star. (His first starring role was in Raoul Walsh’s 1930 movie The Big Trail. But it was John Ford and Stagecoach that made him a star.)

Interestingly, Wayne wasn’t the big star of Stagecoach. Claire Trevor was. She gets top billing and the movie is an ensemble piece, so no one character really dominates as they do in a “star vehicle.”

The movie also gave us Monument Valley, in Utah, which would afterward be forever associated with John Ford and be the quintessential “old West” landscape with its plateaus, mesas and buttes. And for many, this is the movie where Ford’s cinematic eye for people and landscapes — often low-angled shots; often sky dominated — is first seen.

There is one shot in particular that I loved. The upper two thirds of the frame is cloud fluffed sky. The lower third is plateau with a mesa off to the right; nothing but dessert otherwise, but for a trail with the lonely stagecoach winding along it from right to left, small and vulnerable.

The story is simple enough and one that is standard fare now: a group of people on their way from here to there, in this case on a stagecoach, encountering and overcoming various threats along the way.

In this movie, the threat comes from Geronimo as the stagecoach is passing through hostile Apache territory.

Riding the stage with the marshal (George Bancroft) are the “proper” lady, Lucy (Louise Platt) and the banker (Berton Churchill) … and a number of social outsiders. The hooker, the drunk, the outlaw … all with stronger moral codes than those who make up the proper society from which they’re excluded.

Both Dallas (the hooker) and the constantly inebriated Doc Boone (Thomas Mitchell) have been run out of town by self-appointed guardians of social mores.

Along the way, they meet up with the Ringo Kid (John Wayne), the outlaw. Though a disparate group and one at odds with itself, it is in working together that they make it to their destination.

As far as the story goes, the movie is nothing exceptional, at least not today. It’s significance is in what it means historically, as far as cinema goes, and John Ford’s directorial work.

Even though many of the things Ford did have since been copied and have become fairly common, the look of Stagecoach is still striking; more so when seen in its historical context.

For any serious lover of westerns, this movie is a must.

Apart from being at the start of an extraordinary string of westerns from John Ford that cover decades, it also gives us that moment when the camera moves in on John Wayne’s face announcing, in no uncertain terms, “Meet your favourite star for the next forty years.”

Yes, John Wayne was around for a long time after this movie came out. It should also be mentioned that simply as a movie, this is one very good film.

(In this same year, 1939, Ford would also direct Young Mr. Lincoln and Drums Along the Mohawk.)

Black and white and foreign: cognitive adjustments

When I posted Ikiru as part of 20 Movies a few months ago I made reference to the difficulty many people have with movies that are in black and white and movies that are called foreign (and movies that are both, like Ikiru). I mentioned I understood the difficulty, so I’m going to try to explain myself.

When we say we don’t like a movie that is in black and white we don’t really mean we have a problem with it being a monochromatic movie. What we mean is that generally black and white means an older movie and, with an older movie, most of us have to make cognitive adjustments. As a movie begins, that means an impediment to “getting into” the film.

When we say we don’t like a movie that is in black and white we don’t really mean we have a problem with it being a monochromatic movie. What we mean is that generally black and white means an older movie and, with an older movie, most of us have to make cognitive adjustments. As a movie begins, that means an impediment to “getting into” the film.

(People make black and white movies today but when we see those we understand immediately that it is an aesthetic choice. We accept it as part of the film’s craft. With older movies, black and white means colour wasn’t available as an option or that it was an economic decision. So when we say we don’t like black and white we are saying we’re resistant to the movie’s age.)

What does cognitive adjustment mean?

By cognitive adjustments I simply mean we can’t just watch a movie unfold, as we can with most new release movies. We are use to them being in colour; we are use to certain styles (directing, editing, acting). We are use to a certain cultural sensibility. If a movie doesn’t fit with what we’re use to, we have to adjust to accommodate it.

When we see an older movie we usually see different styles; different sensibilities. For myself, having grown up watching a lot of old movies at home on TV with my mother, I am use to these movies. I don’t need to make any adjustment other than to note it is an older movie.

Were I not the age I am and were I not to have had that experience, I would have to make a big adjustment. Those movies would strike me as odd.

The history of film and of acting can be seen in older movies, more so the older they get. We can see how theatre informed films initially and it was only over time that an awareness of film’s intimacy came about. It took time to realize there was no back row to be played to.

As an example of a cognitive adjustment I had to make, I can look at 2005’s Pride and Prejudice. As I first started watching that movie, I resisted it. The style and pace were not what I associated with Jane Austen. In my head, Jane Austen was associated with her novels and, treated visually, BBC productions (seen on the CBC or PBS). Seeing those kinds of TV treatments from decades like the 1980s and 1990s, I anticipated a slower paced, almost literal approach. The movie I saw in 2005 didn’t line up with that. I had to make an adjustment before being able to appreciate the movie I saw.

I think it is a human trait to resist such adjusting. Our first response is to abandon what we’re encountering and simply move on to a different story, a newer movie.

Reading foreign films — subtitles

It is the same thing with a “foreign” movie. For most of us in North America, foreign means non-English. Those foreign movies come from different cultures and societies, so we need to make a cognitive adjustment. Those movies aren’t in English; many therefore come with sub-titles. So there is a linguistic barrier. The sub-titles present yet another barrier – we have to read to understand the dialogue. When we see the words at the bottom of the screen, our eyes drift down to read the words thus taking our attention from the image that is being presented.

The thing is that with most movies, certainly the good ones, you don’t really need the words. The image tells it all; it’s in the acting. Still, our eyes go to those words and we try to read.

Cognitive adjustments are needed to watch a foreign movie.

This why so many people resist such movies whether they’re black and white, foreign, or both. Interestingly, if you see enough of them you do make those adjustments, unconsciously, and it is relatively easy to watch and appreciate the movies. But it is difficult to initially get past those barriers.

There is a fascinating irony or conundrum in all of this. The best movies always demand cognitive adjustments because they ask us to see things in a new way. They make us change the way we think. The difference with black and white and foreign movies is that they are unintended adjustments. They are not a part of the art of the movie we see. They are adjustments required by time and culture.

20 Movies: The Saragossa Manuscript (1965)

I love stories like this. By “this” I mean stories within stories within stories. It’s really quite an accomplishment to achieve something like this on film. But The Saragossa Manuscript manages it.

I don’t recall when I first heard of this movie but it would have been about ten years ago, more or less. When I did, I tracked down a DVD copy. Believe me, I was glad I did.

In a number of ways, this is the perfect movie to wrap up my list of 20 movies.

The Saragossa Manuscript (1965)

directed by Wojciech Has

I won’t even attempt to summarize the plot of The Saragossa Manuscript (Rekpois Znaleziony w Saragossie). (See IMDB for a brief summary.) Rather, I’ll simply say I loved this movie and here’s why: narrative style.

The Saragossa Manuscript, set during the Napoleonic Wars, is told in the manner of and, to a lesser extent, The Canterbury Tales.

It is a story about stories that themselves contain stories (which also contain stories). In some ways, it’s a celebration of storytelling. In the world of written literature, this kind of narrative has a long history. Cinema, however, is a bit different.

Movies are less like novels than they are like short stories and novellas. In other words, a movie story needs to be told all at once (rather than over several days like a TV series or a book you set aside between chapters). Audiences simply can’t (and won’t) sit through 6 or 7 hours (or longer) of film. Nor would budgets allow for the creation of such a monster (Lord of the Rings aside). So films are more compressed (at least when they try to replicate a novel cinematically). Or, with an original script, less wide-ranging and more tightly focused.

Director Wojciech Has achieves a remarkable accomplishment, then, by giving us an engaging film that is wide-ranging and broad. Based on the novel of the same name, and definitely abridged (for the reasons mentioned above), his movie layers story upon story, each somehow touching upon the others, sometimes echoing them, sometimes growing out of and into them.

The result is a delight and, at a running time of 3 hours, one that never flags and loses our attention. Sometimes dark, sometimes bawdy, sometimes funny and sometimes dramatic, in a single film we’re taken into the strange and wonderful world of storytelling.

If there is a theme to it all (beyond the joy of telling stories), it may be the liberating power of fantasy and imagination.

The main character, very focused, disciplined and rigid (on the surface at least), and in denial of anything that doesn’t conform to empirical reality, goes on a journey that transforms him if only by opening him up to possibilities.

Admired by such names as Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese and (oddly) Jerry Garcia, The Saragossa Manuscript DVD is a clean, crisp version (taken in the context of its age and the fact it had to be restored).

Filled with stunning images and moving from the strange to the lascivious to the dramatic, this is a fabulous film and a definite must for anyone who loves stories and wishes to see how film is simply another branch of literature (albiet one with its own rules and traditions).

(Originally posted in 2003.)

See: 20 Movies – The List

20 movies: Tombstone (1993)

I can think of no better place to start my list of twenty movies than with one of my favourite kinds of movies, the western, and specifically one of my favourite westerns, Tombstone from 1993. If you want something to watch this summer, try this one.

While there are many aspects to the movie that are excellent, the one that truly stands out is Val Kilmer’s portrayal of Doc Holliday. If you have never seen the movie, or if you haven’t seen it in a few years, it’s time to watch one of the great performances. In some ways, Tombstone is a variation of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Kilmer’s Holliday is a new take on John Wayne’s Tom Doniphon.

Here’s my review of the movie that I wrote a few years ago:

Tombstone

directed by George P. Cosmatos

This movie frustrates me because I don’t know what to write. It’s one of the best westerns I’ve ever seen and, to be truthful, that’s really all I have to say about it.

Of course, I love westerns. But I’m not sure why. I think it’s because of the simplicity of the stories and the fact that they are, essentially, all mythical.

I suppose you could say this about all movies but westerns, in particular, access mythic elements and use them to engage us. They really are the same damn story played over and over again.

The best westerns do this; the least successful ones try to play with the genre.

Having said that, I think director George P. Cosmatos and writer Kevin Jarre do play with the genre just a tad … but they rigidly adhere to the essential elements. For example, one of the staples of westerns is the opening when the bad guys come in and do something really, really bad. I can’t think of a single Clint Eastwood western that doesn’t do this. What this does is immediately set the context of the movie – a wild and lawless landscape that is crying out for order.

The next step is to introduce us to the good guy (or guys) who are reluctantly drawn in and eventually save the day.

Simple stuff, and exactly what Tombstone does.

But within this simple framework, Cosmatos and Jarre do much more. Chiefly, they give us characters with much greater delineation and far more contradictions that the average B western.

In particular, we get the incredible performance of Val Kilmer as Doc Holliday. It’s not the usual Doc Holliday; this one is true to history and, within that, Kilmer gives us perfect and unexpected nuances.

And while the Doc Holliday character may be the one we walk away remembering best, Kurt Russell’s Wyatt Earp is equally masterful. He’s less interesting only because his character is the good guy. But he has his own contradictions and, more importantly, it’s the apparent paradox of his relationship with Doc Holliday around which the movie revolves and succeeds.

There are, of course, a few minor problems with the film, as with all movies. For example, there is the scene when Bill Paxton as the youngest Earp, Morgan, is shot and Kurt Russell is with him. Russell’s hands and arms are covered in blood. He runs his hands over Paxton’s forehead – he seems to touch just about everyone in the place, including himself – yet no blood rubs off on anyone. Huh? How’d that happen?

But it’s a quibble. The movie is pure western, from setting to music to story. It also avoids that sepia nonsense so many westerns have. Rather, they have shot this movie to show the colour of the mythic west and it’s a tremendous relief to see a western with this much confidence in itself as a western.

Tombstone (the trailer)