This movie is filled with fascinating imagery as Michael Mann presents a nocturnal vision of the city that is dark and threatening. It also has a key image, the coyote, that I think many people misremember. If you look at it closely, it’s not quite the image you think you saw and its meaning is very different when you really see what Michael Mann show us.

Sergio Leone and a good, odd western

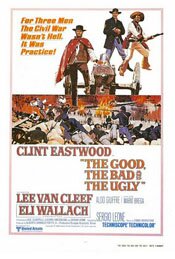

I’m currently reading Marc Eliot’s Clint Eastwood: American Rebel and it inevitably got me thinking about the earlier Eastwood movies, the spaghetti westerns, including The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Below is my lengthy rambling about it from quite a while ago (2000?). For what it is worth …

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Directed by Sergio Leone

One of the best, and oddest, westerns ever made is The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo). It’s hard to imagine anyone making a movie like this today. It’s too long (it would be argued). Some of the scenes, even shots, are too long. Gee, it takes 30 minutes to introduce the three primary characters. What’s that about?

Continue reading

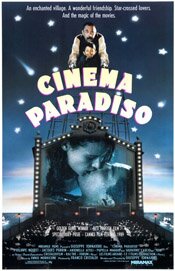

The strange love of movies – Cinema Paradiso

I last watched Cinema Paradiso about ten years ago. I’ve been meaning to watch it again for a long time but two things have held me back: the length (almost three hours — I don’t ever seem to have the time) and what I fear is a problem with my DVD copy. I hate the idea of getting halfway into a movie then finding a problem prevents me from seeing the rest.

But maybe this weekend I’ll overcome these hesitations. I really do want to see this again. For now, my impressions from when I saw it back around 2003 …

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Directed by Giuseppe Tornatore

My memory is poor, so I really don’t recall the original, theatrical version of Cinema Paradiso. Whether or not the longer version I have (the 2003 DVD release) is better, I’ve no idea. It adds 51 minutes to the film – a 174 minute movie compared to the theatrical release at 123.

This version of Cinema Paradiso is broken into three parts – the main character Salvatore as a child, a young man, and finally as an older man (middle-aged). It begins with a kind of prologue of Salvatore as the older man.

The beautiful opening shot is almost still, like a photograph. Slowly the camera pulls back as the opening credits roll. As we pull back, the image we have is truly a filmmaker’s image: it’s very deliberately staged and framed, and I think we’re supposed to be aware of this. It is still, as if frozen, somewhat like the memories of the character Salvatore.

As the camera continues back, we become aware that we’re looking through a window. Slowly retreating, at one moment it almost looks like a film screen.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

The current reality of this beginning (following the opening shot) establishes the kind of life Salvatore is living as a well-known filmmaker. It shows us a man avoiding his past. It gives us a man disconnected from his personal history and disconnected generally with the humanity around him. He’s isolated, and has chosen to be so.

The beginning also is what leads us into the story as it flashbacks to his life as a child, the film’s first section (following its prologue). It’s significant that we get into his childhood this way because it determines what we see and how we see it: it’s through the older Salvatore’s memory. It’s therefore not necessarily true in an objective sense.

This first part, Salvatore as a child (his memory of it), is generally brightly lit. It’s very open and spacious (compare the town square at the beginning of the film to the car-packed square at the end). In fact, everything here is open except for one thing: Alfredo’s little room in the Cinema Paradiso.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Like an image on film limited by the frames, his world is constrained by the walls of his projection room. But as the movie’s opening has shown us, and as demonstrated in Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, there is a world beyond the image’s frame (Tori’s mother in the movie’s opening). However much they may delight, or how real they may seem, movie’s are not everything. There is a world beyond them.

In the second part of the movie, Salvatore begins to become like Alfredo, at least this is a choice he is presented with. He takes over the projection booth. But he does have a choice and this is what the second part concerns.

While isolated in the projection booth, he also has a foot in the more tactile and chaotic world of the audience. This is through his relationship with the young woman Elena. In this part of the film, director Guiseppe Tornatore introduces a sexual element – in the films seen in the Cinema Paradiso, in the behavior of the boys of Salvatore’s age, and in Salvatore’s relationship with Elena, though this latter is more romantic in its treatment than sexual.

But the purpose of the sexuality is its relationship to romance and personal connections. It is something that pulls Salvatore away from the isolated world of films into the community of the audience, the town.

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

Salvatore’s relationship with Elena no longer a possibility, he now leaves the town (the audience). Alfredo not only supports this decision, he prompts it. He tells Salvatore, “You have to go away for a long time, many years, before you can come back and find your people.”

It’s ironic that Alfredo says this as he has never gone away, at least not physically. It could, however, be argued he has left emotionally and spiritually and has yet to return.

This leads to the film’s third part, the movie’s “now.” The older Salvatore finally returns to the town of Giancaldo. He returns for Alfredo’s funeral (who, in a sense, is finally “going away”). For Salvatore, the return is a series of revelations. As he says himself, he has been afraid to return.

One of his biggest discoveries is of Alfredo’s manipulations to keep Salvatore and Elena apart. She did not betray Salvatore, nor he her. It was Alfredo. His reasons were to force Salvatore out to his career as an artist, a famous filmmaker.

The other revelation is the film’s conclusion where Salvatore sits alone in the theatre watching Alfredo’s final gift, a reel of film. It is all the kisses and other intimate moments of human relationships the priest had removed from the movies. It is as if Alfredo is trying to return the part of life he had removed from Alfredo.

In contrast to the film’s beginning, this final section is visually darker and cramped. It is the real part of the film, as opposed to the remembered.

In this final part, we also see the destruction of the theatre, the Cinema Paradiso. While not the destruction of movies, it seems it’s the destruction of the tyranny of fantasy. While painful, it frees Salvatore from the confines imposed by images. It frees him of the prison art imposes and allows him back into life. We see a shot of young people laughing with a youthful sense of fun as they see the destruction of the building. It’s as if the present is clearing away the past so it can live.

The film appears to have two meanings, or at least two intents. In part, it is a loving homage to cinema and what it gives us. At the same time, it is also about the tyranny of art, at least for the artist. It is about what is denied him or her in order to pursue their art. It seems to say, as an artist you can observe life but you cannot be a part of it. You must remain a step removed. And movies are not real. They are moments; they are memories.

I think the film, at least in its extended version, is less a film about a love of cinema than a film about the sacrifices demanded by art. And while it does not provide an answer, I think it also speculates on the relationship between life and art and which has greater value.

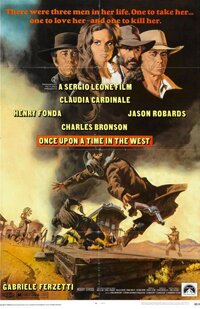

20 Movies: Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Look out. I’m back to westerns. I love them.

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

directed by Sergio Leone

From it’s incredible opening to the closing credits, Once Upon a Time in the West is a mesmerizing movie about westerns. In a way, it isn’t even about westerns. It simply evokes them with a stream of iconic images.

The movie takes a simple, almost cookie cutter story, and uses it as a basis (and excuse) for a film that is essentially concerned with western myths and iconography. (Sergio Leone had done this before, as in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.)

It’s a post-modern film; it takes a kind of deconstructionist approach to movie-making (which may seem a tiresome idea today but was unusual in 1969).

At the centre of the film’s narrative is Claudia Cardinale as Jill. Around her three other characters revolve: Henry Fonda as Frank, Jason Robards as Cheyenne and Charles Bronson as the man with no name (often referred to as Harmonica).

The owner of a railroad company, Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), hires a psychotic gunfighter, Frank (Henry Fonda) to get rid of anyone in the way of the completion of his railroad.

The owner of a railroad company, Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), hires a psychotic gunfighter, Frank (Henry Fonda) to get rid of anyone in the way of the completion of his railroad.

Frank does, by massacring the family of new bride, ex-whore, Jill.

With her new family dead, Jill must decide what to do with the land she has inherited. It seems worthless but proves to be very valuable, so valuable it is the reason her family has been killed. It’s a basic western formula: bad guys after the good guy’s land. He must defend it and himself, except in this case “he” is “she.”

At the same time, bad-guy Frank starts being stalked by a mysterious stranger (Charles Bronson). Frank doesn’t recognize him, he has no idea what the stranger wants. As for Jason Robards’ Cheyenne, he gets involved in all of this because Frank has framed him for the killing of Jill’s family.

At the same time, bad-guy Frank starts being stalked by a mysterious stranger (Charles Bronson). Frank doesn’t recognize him, he has no idea what the stranger wants. As for Jason Robards’ Cheyenne, he gets involved in all of this because Frank has framed him for the killing of Jill’s family.

For a film almost three hours long, it doesn’t seem much to work with. But Leone is interested in the storyline only to the extent that it provides him something to improvise on western themes and imagery. He plays with these and it is what he does with them that makes this such a great movie.

I can’t imagine how this would look in pan-and-scan form. Leone makes incredible use of the screen’s width, visually stretching it out with foregrounds oriented to one side and breathtaking backgrounds to the other.

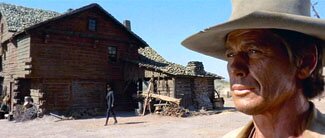

He also contrasts the breadth and spaciousness of his wide shots with the most extreme of close-ups. He shoots human faces almost as if they, too, were landscapes. The opening sequence is a spectacular example of this as he lingers on the bored killers’ faces. He shows us every detail from lines to whiskers. You almost get the sense he uses only two shots – very close or very long.

He also contrasts the breadth and spaciousness of his wide shots with the most extreme of close-ups. He shoots human faces almost as if they, too, were landscapes. The opening sequence is a spectacular example of this as he lingers on the bored killers’ faces. He shows us every detail from lines to whiskers. You almost get the sense he uses only two shots – very close or very long.

He also uses his trademark technique of drawing scenes out to their absolute limit. The opening goes something like eight minutes before anyone says anything and it is a scene simply about three guys waiting at a train station. You get an almost visceral sense of their tedium.

With scenes like gunfights, they are choregraphed to evoke iconic imagery and are paced, again, incredibly slowly to draw them out to their limits. When violence does erupt, it is explosive and very brief. Leone has little interest in violence itself but is obsessed with its rituals.

Whether the movie is about anything is debateable. Leone seems interested primarily in style and evoking the western. (Once Upon a Time in the West is littered with references to earlier Hollywood westerns like High Noon, The Searchers and numerous John Ford films. It’s even partly shot in Monument Valley where Ford shot so many of his westerns.)

Whether the movie is about anything is debateable. Leone seems interested primarily in style and evoking the western. (Once Upon a Time in the West is littered with references to earlier Hollywood westerns like High Noon, The Searchers and numerous John Ford films. It’s even partly shot in Monument Valley where Ford shot so many of his westerns.)

If there is a comment in the film, perhaps it is a critique of myths of America. In the film, everyone is dissatisfied. Everyone wants something more, from the railroad baron and his hired killer Frank, to the woman Jill and Jason Robards. In the land of the free, no one seems to be content with their lot (except, perhaps, for the murdered McBain.)

There may be something to the use of the railroad, too. Its arrival signals the end of the mythological West and the beginning of the modern age in the last American frontier. The train represents encroaching European civilization and the end of the mythical West, just as the film Once Upon a Time in America is a eulogistic end of the western.

There may be something to the use of the railroad, too. Its arrival signals the end of the mythological West and the beginning of the modern age in the last American frontier. The train represents encroaching European civilization and the end of the mythical West, just as the film Once Upon a Time in America is a eulogistic end of the western.

But in the end, the film is simply a great homage to westerns, as well as a kind of eulogy to them. It’s a stream of riveting images; an almost symphonic evocation of filmmaking style.