About three weeks ago I watched The Social Network. I have to watch it again soon because the first experience came as a surprise. It did nothing for me.

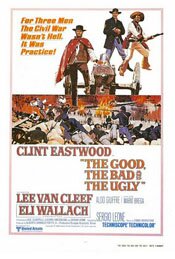

Sergio Leone and a good, odd western

I’m currently reading Marc Eliot’s Clint Eastwood: American Rebel and it inevitably got me thinking about the earlier Eastwood movies, the spaghetti westerns, including The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Below is my lengthy rambling about it from quite a while ago (2000?). For what it is worth …

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Directed by Sergio Leone

One of the best, and oddest, westerns ever made is The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo). It’s hard to imagine anyone making a movie like this today. It’s too long (it would be argued). Some of the scenes, even shots, are too long. Gee, it takes 30 minutes to introduce the three primary characters. What’s that about?

Continue reading

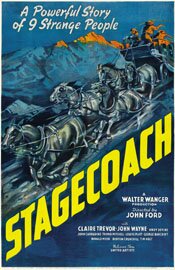

An imposing little Stagecoach from John Ford

When you think of how long it takes to make a movie today, at least a Hollywood movie, it’s quite astonishing to find John Ford cranked out three pretty extraordinary movies in 1939. His “go to” guys in that period were Henry Fonda and John Wayne. (In 1939-1940, he made five films — three with Fonda, two with Wayne.)

The number of movies isn’t the amazing part, though it is notable; what is remarkable is the quality of those films. (The movies are Stagecoach, Young Mr. Lincoln, Drums Along the Mohawk, The Grapes of Wrath and The Long Voyage Home.) For many, that creative glut would be a career. With Ford, some of his best films were still ahead of him.

Stagecoach (1939)

Stagecoach (1939)

Directed by John Ford

For what is essentially a simple western, Stagecoach is a pretty imposing little film. It’s daunting for all the film history associated with it, beginning with the introduction of John Wayne as movie star. (His first starring role was in Raoul Walsh’s 1930 movie The Big Trail. But it was John Ford and Stagecoach that made him a star.)

Interestingly, Wayne wasn’t the big star of Stagecoach. Claire Trevor was. She gets top billing and the movie is an ensemble piece, so no one character really dominates as they do in a “star vehicle.”

The movie also gave us Monument Valley, in Utah, which would afterward be forever associated with John Ford and be the quintessential “old West” landscape with its plateaus, mesas and buttes. And for many, this is the movie where Ford’s cinematic eye for people and landscapes — often low-angled shots; often sky dominated — is first seen.

There is one shot in particular that I loved. The upper two thirds of the frame is cloud fluffed sky. The lower third is plateau with a mesa off to the right; nothing but dessert otherwise, but for a trail with the lonely stagecoach winding along it from right to left, small and vulnerable.

The story is simple enough and one that is standard fare now: a group of people on their way from here to there, in this case on a stagecoach, encountering and overcoming various threats along the way.

In this movie, the threat comes from Geronimo as the stagecoach is passing through hostile Apache territory.

Riding the stage with the marshal (George Bancroft) are the “proper” lady, Lucy (Louise Platt) and the banker (Berton Churchill) … and a number of social outsiders. The hooker, the drunk, the outlaw … all with stronger moral codes than those who make up the proper society from which they’re excluded.

Both Dallas (the hooker) and the constantly inebriated Doc Boone (Thomas Mitchell) have been run out of town by self-appointed guardians of social mores.

Along the way, they meet up with the Ringo Kid (John Wayne), the outlaw. Though a disparate group and one at odds with itself, it is in working together that they make it to their destination.

As far as the story goes, the movie is nothing exceptional, at least not today. It’s significance is in what it means historically, as far as cinema goes, and John Ford’s directorial work.

Even though many of the things Ford did have since been copied and have become fairly common, the look of Stagecoach is still striking; more so when seen in its historical context.

For any serious lover of westerns, this movie is a must.

Apart from being at the start of an extraordinary string of westerns from John Ford that cover decades, it also gives us that moment when the camera moves in on John Wayne’s face announcing, in no uncertain terms, “Meet your favourite star for the next forty years.”

Yes, John Wayne was around for a long time after this movie came out. It should also be mentioned that simply as a movie, this is one very good film.

(In this same year, 1939, Ford would also direct Young Mr. Lincoln and Drums Along the Mohawk.)

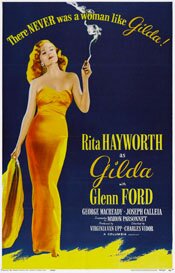

Abuse never looked as beautiful as it does in Gilda

It’s Day 7 of For the Love of Film (Noir) — don’t forget to or use the button on the right. We’re near the end, so now is the time to donate if you haven’t already. If you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down the page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

As much attention as Gilda gets for the beauty and sexiness of Rita Hayworth, what always strikes me is what a mean-spirited, spiteful bastard Glenn Ford is as Johnny Farrell. For about ninety percent of the movie he is abusive and hateful.

Being on the receiving end of it all, Hayworth’s Gilda is a beautiful cry for help. Intentional or not, this movie is a portrait of abuse: verbal, psychological and physical.

Gilda (1946)

Gilda (1946)

Directed by Charles Vidor

The opening of Gilda may be the perfect image for film noir. The camera tilts up from ground level revealing Glenn Ford as Johnny Farrell. He is on his hands and knees, disheveled, hair hanging down over his eyes, as he determinedly rolls his dice.The camera angle makes those dice look huge.

It is almost as if Ford is on the ground groveling.

Compare that to all the heroic shots of John Wayne in those innumerable westerns. Noir and westerns are two sides of one coin, the hero. Being noir, however, the hero must have his femme fatale to muddle up the works for him.

Inevitably, we soon encounter Rita Hayworth as Gilda.

What we soon learn about Johnny and Gilda is that they are really just small time people scrambling to make it in a less than friendly world. Neither really has any admirable characteristics, at least not through most of the movie. (At one point Gilda says, “If I’d been a ranch, they would have called me the Bar Nothing.”)

Yet somehow, for some reason, we’re on their side. Maybe it’s because in the world they inhabit they are slightly better than the other characters and we side with them because we identify with the struggles and compromises made to live in the world.

I’m always fascinated by the dichotomy of westerns and noirs and the idea that they are one thing seen from opposing angles.

When we first meet Gilda she appears like a jack-in-the-box. Her head pops up in such a way that we can’t help but see the lush and luxurious hair and the smile that seems to suggest so much, like playful sex. Everything about Gilda is sex.

For her, it’s both weakness and strength.

We also know immediately, from Johnny’s reaction to Gilda, that “something’s going on there.” They know one another; there is a relationship between them, one that has clearly soured.

The movie is also about relationships that are off in some way. There is anger, even outright hate between Johnny and Gilda, especially on Johnny’s part. As much of a weasel he was in the film’s beginning (and still is, though he has cleaned up his act), he is equally unforgiving. Gilda, encountering his spite, responds in kind.

What we’re not quite sure of is the why of it all. (I don’t recall if this is ever explained other than the fact that Johnny left her, though reasons may be suggested.)

Perhaps what is really askew between Johnny and Gilda is that neither knows what they want. Johnny wants money and power, though I imagine he would be hard pressed to answer why (beyond getting out of the gutter). It seems to be a deflective desire, something pursued in order to forget.

Gilda, on the other hand, hasn’t a clue what she wants. She is entirely reactive – to Johnny’s hate, to the men that use her, to her lack of purpose. (However she, as opposed to Johnny, begins to have an idea as the movie progresses.)

We, on the other hand, pretty much know what both want but won’t admit to themselves: each other. They live in a world of denial; neither wants to articulate the truth about their feelings.

Then there is Ballin Mundson (George Macready). Some argue there is a homoerotic element to Gilda in the relationship between Mundson and Johnny.

Given when the film was made and the shadow of the Hays Code, it would have been difficult to make something like that obvious so, initially, the argument may seem a bit of a stretch.

But the more you think about the movie the more it makes sense. Much of what happens in the film’s first half seems unlikely and arbitrary unless you see a homosexual element to it. One of the things that first struck me was how absurdly convenient it was that Johnny, in a shady part of town, is rescued from thieves by a wealthy man who just happened to be in that end of town. It makes sense, however, if he is in that part of town looking to pick someone up for sex.

The relationship that develops between Johnny and Mundson makes more sense in this context.

Johnny’s taken into Mundson’s world, given a position of authority and trust, becomes his right hand man, given access to Mundson’s wealth (including the safe) … And it all happens very quickly.

It all seems a little too convenient unless you consider there is something like a gay relationship between the two (though not a healthy gay relationship). It gains credibility if you see the relationship of Johnny to Mundson as similar to Sunset Boulevard‘s Joe Gillis to Norma Desmond.

It also adds another element to Johnny’s dislike of Gilda: there is a previous relationship between them but there is also the fact that, with Gilda as Mundson’s new wife, she is intruding on Johnny’s position.

Though it may be a bit of a long shot as far as interpretations go, I like to think that homoerotic aspect is there. It helps make sense of what are otherwise puzzling story elements and also adds a nice bit of irony in that it is present in a movie known for its heterosexual quality, the “love goddess” Rita Hayworth, famous for making heterosexual men crazy with longing.

When you get past the glitz and spectacle of Rita Hayworth’s famous sultry sexuality in the movie, the more you can’t help thinking this is one crazy movie about abuse and aberrant psychology. And you know, despite the happy gloss of the ending, that it will continue. Johnny and Gilda may have mended their fences and be doe-eyed once again, but the abuse will be back.

(Note: Rita Hayworth and Glenn Ford would be teamed again six years later in 1952’s Affair in Trinidad, an attempt to jump start Rita’s career and a poor knock off of Gilda.)

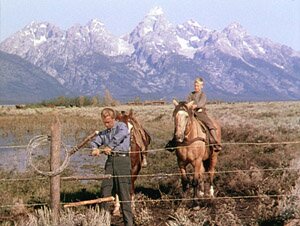

Is Shane too aware of itself as a western?

I wrote the bit below about 8 to 10 years ago after seeing Shane for the first time. It’s strictly a gut response and an attempt to figure out that gut response. But I think it may be time for me to re-watch this movie and see if I still have the same reaction or if I can finally see what many others see in the movie.

Shane (1953)

Shane (1953)

Directed by George Stevens

I’ve never seen Shane before. I haven’t discussed it in a film studies class. I haven’t spent hours in bars or cafes talking about it. I just like westerns, knew it was considered one of the best, and finally decided to watch it. So my reaction to it is, in many ways, fresh and not particularly tainted by what others think of it.

Gut response? I was a bit bored. But I’m not so sure it’s a fault of the movie so much as it’s a problem that the film’s sensibilities are of a time when they were not as frenetic as they are now. People were a bit more open to a more leisurely pace.

On the other hand, some of the problems were not just sensibility and the film’s tempo. Shane suffers, I think, from being a little too self-conscious. It’s a little too aware of the western genre, of its place in it, and of its purpose, which is too comment on the genre and film violence.

Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time.

Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time.

Shane arrives at a Wyoming homestead as a drifter. He stays for a while with people who are oppressed by cattlemen trying to take over their land. He is distant but suggests strength. Men and women admire and respect him, children hero-worship him. Eventually troubles with the cattlemen come to a head and it is Shane who faces them down.

Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence.

Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence.

The result is a lot of time spent on creating the non-violent world represented by Marion (Jean Arthur) and her husband-farmer played by Van Heflin. (He, by the way, is absolutely perfect in this role; his performance is nothing less than great.)

Unfortunately, the family life, the life of hard work, is not particularly interesting. To appreciate the value of this kind of life you have to live it. To watch it is to go to sleep.

We get to see Shane watching this life, and see his longing for it (an essential element in the film) but again, it’s a bit of a snooze. It’s one of the hardest tasks an artist can set him or herself: to make the lives of nice people interesting for an audience. It is seldom done successfully.

Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained.

Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained.

This is all just gut reaction but I really think Shane falls short primarily for one reason: it’s a movie for the intellect and not for the gonads. Westerns are meat-and-potatoes films. They are best when they’re simple. They’re best when they follow formulas. They are best when they tell you things that are true viscerally, not via the brain.

(Note: This review was written back around 2003. It was my initial response to my first viewing of the movie.)

20 Movies: Destry Rides Again (1939)

I love movies that surprise me. When I picked up this one a few years ago I really had no idea what to expect. I had never even heard of it. What a fabulous surprise it was!

It doesn’t pretend to be anything more than what it is: an entertaining western and comedy. But it succeeds wonderfully and is great fun to watch.

Destry Rides Again (1939)

directed by George Marshall

I think the best word to describe this movie is fun. Following the disappointment a few weeks ago of Five Card Stud, this western, Destry Rides Again, was a real treat.

Made in 1939, this is both a traditional Hollywood western in some respects, and in others a great spoof of those movies. At heart, it’s a comedy but, despite this, it also throws in the requisite western scenes. Often, however, there’s a certain tongue in cheek quality to them.

The story is pure western: the town of Bottleneck (great name!) is lawless. There’s a nasty land baron trying to seize the necessary lands to complete his control of the area. Once his, he can charge others inflated prices to cross those lands.

The town sheriff, trying to impose some law, is shot and killed, his body disposed of in such a way that it won’t be found. The corrupt town mayor then appoints the town drunk as sheriff.

Now there is no law in Bottleneck. But … The town drunk sobers up.

He takes his bogus position seriously and therefore sends for Destry (Jimmy Stewart), the son of another famous lawman.

Destry arrives and the fun really gets going. He’s not what anyone expects.

He’s calm, relatively mild-mannered, doesn’t wear guns … doesn’t even like guns. And of course, this sets up the final scenes when (as we can expect) he finally is pushed to a point where he does put on guns (a similar situation to Clint Eastwood’s Pale Rider).

In the meantime, the filmmakers and the audience have loads of fun, including a cat fight between an angry wife and the town floozy, Marlene Dietrich.

In Destry Rides Again, Jimmy Stewart is perfect – he is so Jimmy Stewart. His famous halting pattern of speech is used comedically to suggest a kind of slyness. It shows the awareness and intelligence behind his character’s meek exterior so we know this quality is part of the character’s act.

As an audience, we realize there is more to him than the meek exterior we see.

Dietrich is also good, though the name Frenchy doesn’t quite fit her German accent … but I suppose that’s quibbling.

Unlike some parodies that simply mock a style, films that choose to take a kind of “looking down the nose” approach, Destry Rides Again seems to love westerns and love using the style to have fun. And it works brilliantly. It’s a movie that succeeds as a western and as a comedy. Ultimately, it is simply a lot of fun to watch.

Highly recommended. (See also: Along Came Jones)

See: 20 Movies – The List

Destry Rides Again (bar scene)

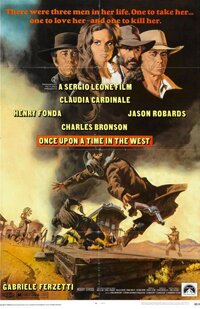

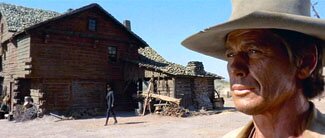

20 Movies: Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Look out. I’m back to westerns. I love them.

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

directed by Sergio Leone

From it’s incredible opening to the closing credits, Once Upon a Time in the West is a mesmerizing movie about westerns. In a way, it isn’t even about westerns. It simply evokes them with a stream of iconic images.

The movie takes a simple, almost cookie cutter story, and uses it as a basis (and excuse) for a film that is essentially concerned with western myths and iconography. (Sergio Leone had done this before, as in The Good, the Bad and the Ugly.)

It’s a post-modern film; it takes a kind of deconstructionist approach to movie-making (which may seem a tiresome idea today but was unusual in 1969).

At the centre of the film’s narrative is Claudia Cardinale as Jill. Around her three other characters revolve: Henry Fonda as Frank, Jason Robards as Cheyenne and Charles Bronson as the man with no name (often referred to as Harmonica).

The owner of a railroad company, Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), hires a psychotic gunfighter, Frank (Henry Fonda) to get rid of anyone in the way of the completion of his railroad.

The owner of a railroad company, Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti), hires a psychotic gunfighter, Frank (Henry Fonda) to get rid of anyone in the way of the completion of his railroad.

Frank does, by massacring the family of new bride, ex-whore, Jill.

With her new family dead, Jill must decide what to do with the land she has inherited. It seems worthless but proves to be very valuable, so valuable it is the reason her family has been killed. It’s a basic western formula: bad guys after the good guy’s land. He must defend it and himself, except in this case “he” is “she.”

At the same time, bad-guy Frank starts being stalked by a mysterious stranger (Charles Bronson). Frank doesn’t recognize him, he has no idea what the stranger wants. As for Jason Robards’ Cheyenne, he gets involved in all of this because Frank has framed him for the killing of Jill’s family.

At the same time, bad-guy Frank starts being stalked by a mysterious stranger (Charles Bronson). Frank doesn’t recognize him, he has no idea what the stranger wants. As for Jason Robards’ Cheyenne, he gets involved in all of this because Frank has framed him for the killing of Jill’s family.

For a film almost three hours long, it doesn’t seem much to work with. But Leone is interested in the storyline only to the extent that it provides him something to improvise on western themes and imagery. He plays with these and it is what he does with them that makes this such a great movie.

I can’t imagine how this would look in pan-and-scan form. Leone makes incredible use of the screen’s width, visually stretching it out with foregrounds oriented to one side and breathtaking backgrounds to the other.

He also contrasts the breadth and spaciousness of his wide shots with the most extreme of close-ups. He shoots human faces almost as if they, too, were landscapes. The opening sequence is a spectacular example of this as he lingers on the bored killers’ faces. He shows us every detail from lines to whiskers. You almost get the sense he uses only two shots – very close or very long.

He also contrasts the breadth and spaciousness of his wide shots with the most extreme of close-ups. He shoots human faces almost as if they, too, were landscapes. The opening sequence is a spectacular example of this as he lingers on the bored killers’ faces. He shows us every detail from lines to whiskers. You almost get the sense he uses only two shots – very close or very long.

He also uses his trademark technique of drawing scenes out to their absolute limit. The opening goes something like eight minutes before anyone says anything and it is a scene simply about three guys waiting at a train station. You get an almost visceral sense of their tedium.

With scenes like gunfights, they are choregraphed to evoke iconic imagery and are paced, again, incredibly slowly to draw them out to their limits. When violence does erupt, it is explosive and very brief. Leone has little interest in violence itself but is obsessed with its rituals.

Whether the movie is about anything is debateable. Leone seems interested primarily in style and evoking the western. (Once Upon a Time in the West is littered with references to earlier Hollywood westerns like High Noon, The Searchers and numerous John Ford films. It’s even partly shot in Monument Valley where Ford shot so many of his westerns.)

Whether the movie is about anything is debateable. Leone seems interested primarily in style and evoking the western. (Once Upon a Time in the West is littered with references to earlier Hollywood westerns like High Noon, The Searchers and numerous John Ford films. It’s even partly shot in Monument Valley where Ford shot so many of his westerns.)

If there is a comment in the film, perhaps it is a critique of myths of America. In the film, everyone is dissatisfied. Everyone wants something more, from the railroad baron and his hired killer Frank, to the woman Jill and Jason Robards. In the land of the free, no one seems to be content with their lot (except, perhaps, for the murdered McBain.)

There may be something to the use of the railroad, too. Its arrival signals the end of the mythological West and the beginning of the modern age in the last American frontier. The train represents encroaching European civilization and the end of the mythical West, just as the film Once Upon a Time in America is a eulogistic end of the western.

There may be something to the use of the railroad, too. Its arrival signals the end of the mythological West and the beginning of the modern age in the last American frontier. The train represents encroaching European civilization and the end of the mythical West, just as the film Once Upon a Time in America is a eulogistic end of the western.

But in the end, the film is simply a great homage to westerns, as well as a kind of eulogy to them. It’s a stream of riveting images; an almost symphonic evocation of filmmaking style.

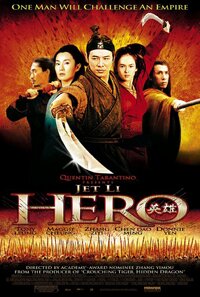

20 Movies: Hero (Ying xiong) (2002)

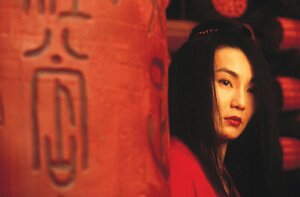

It seems appropriate that a movie that is mythic and fantastic should also be fantastic, not in the fantasy sense but in the Wow! sense. To a degree, the story is irrelevant here because the movie is so visually stunning, partly due to the acrobatic swordplay scenes but primarily through the use of colour and staging of scenes.

But there is more to Hero than its look. At its heart, it is romantic. It’s romantic in its view of China’s history and it’s romantic in the relationships between characters. As story ingredients go, there are few things as engaging as romance.

Hero (Ying xiong) (2002)

Hero (Ying xiong) (2002)

directed by Yimou Zhang

With a movie as good as Hero, where do you begin? There are so many elements, so many perspectives, so many levels that warrant lengthy discussion it’s almost impossible to start.

So I’ll begin by first saying my knowledge of China, it’s history and culture and everything else, could be put on the head of pin and still leave room. My ignorance is boundless so anything I have to say comes from a totally western perspective.

But that’s okay because, like any worthwhile art, Hero is a movie for everyone and likely becomes more interesting as more perspectives and interpretations are brought to it.

Set roughly 2,000 years ago in China, Hero is about the beginning of China’s unification as a single nation under the harsh leadership of the King of Qin (played by Daoming Chen).

As mentioned, I know nothing of China but my guess is that Hero is a little bit of history, a little bit of legend and a fairly loose interpretation of both.

As mentioned, I know nothing of China but my guess is that Hero is a little bit of history, a little bit of legend and a fairly loose interpretation of both.

The king has his enemies and the movie begins with a man called Nameless (Jet Li) coming to the emperor to say he has destroyed his three greatest enemies: Sky (Donnie Yen), Broken Sword (Tony Leung Chiu Wai) and Flying Snow (Maggie Cheung). Nameless, in the emperor’s court, tells the king of how he killed these three.

While comparisons have been made between Hero and Akira Kurosawa’s Rashoman, this is a bit misleading. They are similar, however, to the extent that Hero tells the story of the three enemies and their ruin from different perspectives (including the king’s) and not necessarily truthfully. (As Yunda Eddie Feng at suggests, a better comparison might be to The Usual Suspects.)

The film, then, moves inexorably toward its truth and this is where the film’s title, Hero, becomes interesting. Who is the hero? There appear to be several.

The film, then, moves inexorably toward its truth and this is where the film’s title, Hero, becomes interesting. Who is the hero? There appear to be several.

I understand that ying xiong doesn’t distinguish between singular and plural (as we do with the English hero and heroes). I don’t know, but it is certainly one of the interesting aspects of the film – what is a hero and what makes him or her heroic?

In the movie, despite it’s Hong Kong martial arts and swordplay, the implicit violence of swords is downplayed.

One of the film’s keys is the idea of swordsmanship and calligraphy being connected. Calligraphy is a hugely important element of the film.

One of the film’s keys is the idea of swordsmanship and calligraphy being connected. Calligraphy is a hugely important element of the film.

The movie overall is lyrical, even poetic. Similar to Ang Lee’s approach in Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, the film is more interested in the romance of its story than in any other element. It’s from this romance the lyricism is drawn and it is what unifies the entire film.

And while there is romance of the love variety, the greater romance is in the view of heroism – sacrifice and honour.

For me, the best martial arts films are like the best westerns. In fact, I think they are essentially the same genres but from different (though dovetailing) cultures.

Both are at their best when informed by morality and romance. I would argue (and have argued) that these two genres (martial arts and westerns) are the same, and are essentially romantic, moral tales given a deceptive high adventure gloss.

Both are at their best when informed by morality and romance. I would argue (and have argued) that these two genres (martial arts and westerns) are the same, and are essentially romantic, moral tales given a deceptive high adventure gloss.

From my admittedly limited perspective, what Hero most reminds me of are the great films of Sergio Leone like The Good, The Bad and the Ugly and Once Upon a Time in the West. It’s not just in the type of story but also the way it is told.

Like Leone’s films, I can’t image Hero in anything but widescreen. The cinematography of Christopher Doyle is breathtaking.

The way scenes are framed, spread across the screen, elements juxtaposed, gives the movie its epic and legendary look.

And while I see many movies use colour (usually in an annoying way), in Hero colour literally tells the story.

And while I see many movies use colour (usually in an annoying way), in Hero colour literally tells the story.

Working in tandem with the wonderful music of Tan Dun, the story gets told almost without the necessity of words.

Hero isn’t just a good movie, it’s a great movie. It’s epic and rich and a veritable visual feast … even if, like me, you know next to nothing about China.

See: 20 Movies – The List

Hero (the trailer):

20 movies: Tombstone (1993)

I can think of no better place to start my list of twenty movies than with one of my favourite kinds of movies, the western, and specifically one of my favourite westerns, Tombstone from 1993. If you want something to watch this summer, try this one.

While there are many aspects to the movie that are excellent, the one that truly stands out is Val Kilmer’s portrayal of Doc Holliday. If you have never seen the movie, or if you haven’t seen it in a few years, it’s time to watch one of the great performances. In some ways, Tombstone is a variation of The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Kilmer’s Holliday is a new take on John Wayne’s Tom Doniphon.

Here’s my review of the movie that I wrote a few years ago:

Tombstone

directed by George P. Cosmatos

This movie frustrates me because I don’t know what to write. It’s one of the best westerns I’ve ever seen and, to be truthful, that’s really all I have to say about it.

Of course, I love westerns. But I’m not sure why. I think it’s because of the simplicity of the stories and the fact that they are, essentially, all mythical.

I suppose you could say this about all movies but westerns, in particular, access mythic elements and use them to engage us. They really are the same damn story played over and over again.

The best westerns do this; the least successful ones try to play with the genre.

Having said that, I think director George P. Cosmatos and writer Kevin Jarre do play with the genre just a tad … but they rigidly adhere to the essential elements. For example, one of the staples of westerns is the opening when the bad guys come in and do something really, really bad. I can’t think of a single Clint Eastwood western that doesn’t do this. What this does is immediately set the context of the movie – a wild and lawless landscape that is crying out for order.

The next step is to introduce us to the good guy (or guys) who are reluctantly drawn in and eventually save the day.

Simple stuff, and exactly what Tombstone does.

But within this simple framework, Cosmatos and Jarre do much more. Chiefly, they give us characters with much greater delineation and far more contradictions that the average B western.

In particular, we get the incredible performance of Val Kilmer as Doc Holliday. It’s not the usual Doc Holliday; this one is true to history and, within that, Kilmer gives us perfect and unexpected nuances.

And while the Doc Holliday character may be the one we walk away remembering best, Kurt Russell’s Wyatt Earp is equally masterful. He’s less interesting only because his character is the good guy. But he has his own contradictions and, more importantly, it’s the apparent paradox of his relationship with Doc Holliday around which the movie revolves and succeeds.

There are, of course, a few minor problems with the film, as with all movies. For example, there is the scene when Bill Paxton as the youngest Earp, Morgan, is shot and Kurt Russell is with him. Russell’s hands and arms are covered in blood. He runs his hands over Paxton’s forehead – he seems to touch just about everyone in the place, including himself – yet no blood rubs off on anyone. Huh? How’d that happen?

But it’s a quibble. The movie is pure western, from setting to music to story. It also avoids that sepia nonsense so many westerns have. Rather, they have shot this movie to show the colour of the mythic west and it’s a tremendous relief to see a western with this much confidence in itself as a western.

Tombstone (the trailer)