Edward G. Robinson was one helluva a good actor. He even makes this exercise in the absurd and perfunctory a crime drama you can watch, even enjoy at moments. Often found in film noir collections, it isn’t noir. In a way, it’s screwball comedy without the humour.

Can a film noir be too perfectly noir?

I think I’m one of the few people who doesn’t care much for Out of the Past. It may be that for me the closer a movie gets to film noir, the less it appeals to me. I can’t argue with any of the superlatives used to describe this one. But despite all it does right in terms of noir, I can’t get terribly enthused.

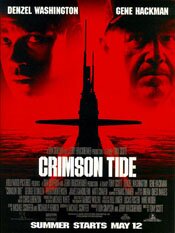

Characters in close quarters – Crimson Tide

You wouldn’t immediately associate submarine movies with a film like Key Largo but they have something in common. The dramatic tension comes about by having characters constrained within close quarters. In Key Largo, it’s within a hotel because of a hurricane; in submarine movies it’s due to the nature of submarines.

I don’t like a phrase like “submarine movies” but there is no getting around the fact there is a kind of sub-category of action-adventure films characterized by where they are set — on submarines. They’re often among the best of the action-adventure variety of films because of the close quarters that seem to force filmmakers to concentrate on characters.

Crimson Tide (1995)

Crimson Tide (1995)

Directed by Tony Scott

In the tradition of movies like Run Silent, Run Deep, The Hunt for Red October and Das Boot, the Tony Scott directed Crimson Tide is submarine drama with strong lead characters. If it distinguishes itself from those previous movies it is by being faster moving and much noisier.

That may not sound overly appealing but it be would wrong to think that way. This is a very good, very engaging action-adventure with a strong foundation: the performances of Denzel Washington and Gene Hackman.

It’s also supported by strong performances by its supporting cast – Matt Craven, George Dzundza, Viggo Mortensen and James Gandolfini, to name a few.

Without its strong cast, I think this would likely be just an average film but with them it is firmly anchored.

There is a state civil war in Russia. Rebel generals have taken over a base with nuclear weapons and it appears as if they may use them. The U.S. naval sub Alabama, nuclear-armed, is sent to Asian waters to await instructions. They get them: prepare your missiles. A further message, only partially received, may be orders to fire them or to stand down. It is unclear.

The movie’s conflict is between the sub’s captain (Gene Hackman) and its new executive officer (Denzel Washington). For the missiles to be fired, the two must be in agreement. They aren’t. The captain wants to fire; his second in command does not.

What makes movies like this dramatic and appealing (and you see this in films like Run Silent and Red October) is that the “bad guy” is external – off set. The leads, in this case Hackman and Washington, are both good guys but they are at opposing ends about what to do and thus in conflict.

This increases the film’s conflict by removing the easy, black and white choice and while an audiences’ sympathy may align with one, they can’t easily dismiss the other.

This is also reflected in the unfolding of the film’s drama where the sub’s crew must choose sides, many of whom are conflicted (like Mortensen’s Lt. Ince). We end up with struggles in the submarine, including mutiny, because of the lack of clarity. It’s all due to the ambiguity of the last orders received.

The movie doesn’t ease its audience into the story; it throws them in head first. Music and editing thrum as it begins with a journalist describing events in Russia. There is no slow unfolding of exposition. Director Scott and producer Jerry Bruckheimer take the approach of throwing the audience in at full speed. Details fly by like rapid fire flash cards.

In some movies, this is noise and fury approach can be a gimmick to mask an uninspired story but in Crimson Tide it’s a quick and effective way to get quickly to what is an intelligent, well told story. Perhaps its due to the close quarters of submarines, but movies like this seem to lend themselves to dramatic, character-driven films.

While my own preference is for the quieter tension of a movie like The Hunt for Red October (which I find more effective), it works for Crimson Tide as it delivers a compelling film that leaves an audience with something to question and discuss when is over.

On the whole, this is a very good movie and well worth seeing and more than once.

Barbara Stanwyck must have liked working

Without intending to, I’ve found myself watching a lot of Barbara Stanwyck movies lately, including Double Indemnity (of which I’d like to scribble something one of these days). I believe IMDb shows she appeared in 101 movies and TV shows in her career. She really must have liked working.

I realized I have 18 Stanwyck movies on DVD (only a small number relative to her output). Of those, I’ve watched 15. There are three I’ve yet to see (but plan to): To Please a Lady, Jeopardy and Stella Dallas. Of the 15 watched, I’ve only written about a few, such as this one below. I watched it just last week.

My Reputation (1946)

Directed by Curtis Bernhardt

It seems a strange thing to say but My Reputation suffers from an actor’s performance that is too good.

Barbara Stanwyck portrays Jessica Drummond so well, you almost fume with frustration with her in the movie’s first half.

That’s not actually the case, however.

The problem is the movie and using its first third to create a portrait of a conflicted woman – it’s really a lot of exposition. As the Variety review from 1945 points out, the movie’s other star, George Brent, doesn’t make an appearance for about a half hour or so.

My Reputation is a romantic melodrama and, once the first third is over and certain things are established, entertaining in an average kind of way. Actually, thanks to Stanwyck’s performance, it’s above average. While a romance, it is also about psychological conflict and it’s that element where Stanwyck really excels.

Jessica Drummond is a recent widow who suffers from a domineering mother and friends who are superficial at best. She wants to assert herself as an individual, having been lost for years as secondary to others, but she can’t bring herself to do so. She makes a number of false starts.

This is what I mean about frustration: Stanwyck portrays the conflict so well that, if you are me, while sympathetic you want to tear your hair out because she is so mousy. However, once a new love shows up in the form of George Brent as Major Scott Landis the movie picks up as Stanwyck’s character becomes increasingly stronger.

It’s true the movie is dated, as some have pointed out, but I didn’t find that a particularly difficult barrier to get past, no more so than a historical film or book would be. It’s not a movie for everyone – despite the psychological aspect, it’s essentially a love story, a romantic fantasy.

If you don’t like romances, you probably won’t like this movie. On the other hand, if you want to see yet another brilliant Barbara Stanwyck performance, you really shouldn’t miss this one.

Blogathon Update:

- Self-Styled Siren has an update on the For the Love of Film (Noir) blogathon, including a specifically for the blogathon. Get ready! It begins Valentine’s Day (February 14) and runs through till February 21. Oddles of bloggers talking about film noir and film preservation.

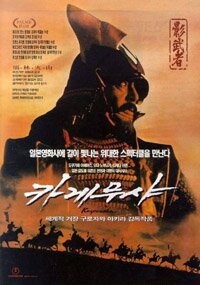

20 Movies: Kagemusha (1980)

This is a review I wrote a few years ago when I first picked up the DVD of Kagemusha and saw it for the second time, some twenty years after first seeing it. I think I might write something quite different today.

Somewhere on my computer I have a post about old black and white movies and “foreign” films and how, in certain ways, they involve cognitive barriers we have to get past to enjoy the movie. In the case of Kagemusha, it would be the language, Japanese (unless, of course, you speak Japanese). You don’t understand the language; you follow subtitles. That creates a barrier of sorts that you have to adjust to.

Kagemusha is one of the first movies of the subtitles kind that I saw and probably the first where the adjusting was almost non-existent. It was so visually brilliant I was enthralled from the start. Prior to Kagemusha, my movie experience was almost exclusively Hollywood. I’m still essentially a Hollywood formed viewer but it is probably Akira Kurosawa more than any other director that brought me into a world of film beyond the restrictive Hollywood definition.

Kagemusha (1980)

Kagemusha (1980)

directed by Akira Kurosawa

I probably saw the movie Kagemusha first back in 1980 or 1981, when it was first released in North America with 20 minutes removed from the film Akira Kurosawa made. At the time, it knocked me for a loop.

It was the first Kurosawa movie I had seen. It was also the first samurai film I had seen. I don’t recall many other movies that so impressed me visually. Also, back then, my cinematic references were almost entirely western, as in Hollywood, with maybe a few Fellini films tossed in the mix.

So here was a colourful samurai movie in Japanese with English subtitles. Going in, I was a bit trepidatious. Going out, I was ga-ga.

That was more than twenty years ago. I’ve not seen Kagemusha since, not till last night when I watched the Criterion DVD – Kurosawa’s fully restored, 180 minute version in a transfer that is outstanding.

In those intervening twenty odd years I’ve seen many more kinds of film, many more samurai films and many more Akira Kurosawa films, including some of his non-samurai movies like Ikiru.

In those intervening twenty odd years I’ve seen many more kinds of film, many more samurai films and many more Akira Kurosawa films, including some of his non-samurai movies like Ikiru.

So the virgin quality of my first experience of Kagemusha is gone; it’s visual impact has been lessened in that sense. On the other hand, while no expert I’m still a bit more visually conversant than I was then, a bit more attentive and aware, not so impressed by something that looks “cool.” In that sense, the visual impact of the movie has been heightened.

The movie is about a thief, one condemned to die by crucifixion, but is spared because he looks so much like the leader of the Takeda clan, Shingen. It is Shingen’s brother who has discovered the thief’s resemblance, the same brother who has also been acting as Shingen’s double (a kagemusha) as a strategic tool in their conflict with other clans.

The movie is about a thief, one condemned to die by crucifixion, but is spared because he looks so much like the leader of the Takeda clan, Shingen. It is Shingen’s brother who has discovered the thief’s resemblance, the same brother who has also been acting as Shingen’s double (a kagemusha) as a strategic tool in their conflict with other clans.

The thief does become a kagemusha for the Takeda leader but then Shingen is mortally wounded by a sniper. Before he dies, Shingen makes his final wish known – to not reveal the fact of his death until three years after he has died and to use that time to pull back and consolidate the Takeda position.

The thief then becomes a kagemusha for Shingen in earnest. He does it so well, he fools almost all and thus makes the other clans uncertain – fearful of Shingen and confused about his intentions.

As the film evolves, it becomes a meditation on the nature of power and of leaders while at the same time moving forward with a tragic, inexorable determination.

I’m struck by several things about Kagemusha (including how long the movie is). I suppose more than anything I’m taken by how controlled and deliberate it seems, how managed each shot is.

It begins with the very first scene. It’s a fairly lengthy one where the warrior Shingen and his brother (who has acted as Shingen’s double in the past) first meet the kagemusha (“double” or “shadow” – hence the film’s title sometimes being referred to as Kagemusha: the Shadow Warrior).

The scene is a single, static shot – no cuts, no camera movement. The actors sit Japanese style on the floor and are exactingly positioned to compose the shot. They make a set of three elements placed deliberately in the foreground – two (the brothers) are centre and left. Of the two, one (Shingen, in the middle) is slightly above. The third characer or element, the kagemusha, is off to the right, also below the middle element, Shingen.

This composition of three, or variations of it, occurs over and over throughout the movie. (If I recall correctly, we also see it used in the opening of his next movie, Ran.)

Other than simply liking this kind of composition, I’m not sure what significance it has for Kurosawa. For me, however, it communicates order and a sense of control, or at least its illusion.

It contrasts starkly with where Kurosawa’s film ends up taking us – the disorder of the battlefield after the conflict, and perhaps even the movie’s final image of the kagemusha being carried off by a current in the sea, that image composed in such a way as to severe the “canvas” against which the compositions of three were placed. (Alright, that last bit may be a stretch.)

It contrasts starkly with where Kurosawa’s film ends up taking us – the disorder of the battlefield after the conflict, and perhaps even the movie’s final image of the kagemusha being carried off by a current in the sea, that image composed in such a way as to severe the “canvas” against which the compositions of three were placed. (Alright, that last bit may be a stretch.)

In his later samurai movies (Kagemusha and Ran), Kurosawa takes a very painterly approach, and also a very deliberate one. As mentioned, the film struck me by its length. This is partly because it is long – three hours – but also because it begins slowly and (to repeat myself) deliberately as the beginning goes through a lengthy exposition.

But it’s not simply story exposition. It’s visual exposition too, those brilliant compositions of order. Interestingly, contrasted against the structural order of the way each scene is composed is the content, or story itself, which is somewhat confusing as we have several people playing, to some degree, one character – Shingen, the brother and the kagemusha. In the first half hour, it’s not difficult to get these confused.

For me, Kagemusha is a wonderful, if somewhat difficult movie. I think Ran is the better film. Kagemusha, however, is a film Kurosawa needed to make in order to get to Ran. Many of the visual ideas about composition and colour are first explored here. The movie is also an initial iteration of the theme of chaos and order, their roots and the illusions that attend the ideas of power, control and position.

For me, Kagemusha is a wonderful, if somewhat difficult movie. I think Ran is the better film. Kagemusha, however, is a film Kurosawa needed to make in order to get to Ran. Many of the visual ideas about composition and colour are first explored here. The movie is also an initial iteration of the theme of chaos and order, their roots and the illusions that attend the ideas of power, control and position.

Finally, Kagemusha is well worth seeing if only to sit back and let absolutely stunning images wash over you. This is one of the best looking movies I’ve seen.

See: 20 Movies — The List

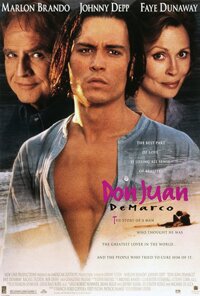

20 Movies: Don Juan DeMarco (1994)

As the muddle below that pretends to be a review indicates, I’m all at sea on this one. I love the movie but my head keeps going, “This is ain’t so great.” I’ve decided I like it because 1) I love Johnny Depp’s performance and, 2) there are some really great lines (that wouldn’t work without Depp’s delivery). I have a problem with it because Brando is so damn Brando.

Still, I really love this movie.

Don Juan DeMarco (1994)

Don Juan DeMarco (1994)

directed by Jeremy Leven

“There are only four questions of value in life, Don Octavio. What is sacred? Of what is the spirit made? What is worth living for, and what is worth dying for? The answer to each is the same: only love.”

— Don Juan DeMarco —

This movie is either a brilliant failure or a flawed success. I’m not sure which. As much as I like Don Juan DeMarco, it’s one weird little film. It’s not weird in the sense of bizarre but in the odd mix of flaws and virtues. Such as:

- It’s wildly romantic, in an over-the-top kind of way, yet it’s appropriate for its subject, romantic love.

- Because of its romanticism, the writing is often lyrical and sentimental – too much so, you would think, yet it isn’t and contains some marvelous lines.

-

Johnny Depp gives one of my favourite performances as the young man who believes he is Don Juan. This really is his film.

Johnny Depp gives one of my favourite performances as the young man who believes he is Don Juan. This really is his film.

- Marlon Brando gives a performance that is peculiar in that in some scenes he is dead on and others he seems asleep at the wheel. It’s definitely a Brando interpretation with all that is puzzling about that.

- Faye Dunaway plays a supporting role yet, while having less screen time, manages to have some of the most poignant scenes and, frankly, seems to spark Brando to life. His best scenes are with her. She seems to do for Brando what Don Juan does for Dr. Mickler: wake him up.

- Some of the flashback scenes are a bit tedious, less for what they are than for what they are not. The story is in the relationship between Dr. Mickler (Marlon Brando) and Don Juan (Johnny Depp). When they move from that to what is essentially exposition, the story sags somewhat. (Admittedly, however, I didn’t think this when I first saw the movie.)

So I don’t know what to think. However, I do know I love the movie. Heaven knows I’ve watched it enough times. I think when I saw it the first time it was that romantic, lyrical language that first hooked me. The movie is also funny, in an understated way (as it’s intended to be).

So I don’t know what to think. However, I do know I love the movie. Heaven knows I’ve watched it enough times. I think when I saw it the first time it was that romantic, lyrical language that first hooked me. The movie is also funny, in an understated way (as it’s intended to be).

The main problem with the movie is Brando. It’s a very uneven performance. The younger Brando would have blown this Brando off the screen. As it is, Johnny Depp blows him off the screen. And this is a big problem because Dr. Mickler is at the heart of the movie. He has been sleeping for years; Don Juan wakes him up.

“What is this thing that happens with age? Why does everyone want to pervert love and suck it bone dry of all its glory? Why do you bother to call it love anymore?”

— Don Juan DeMarco —

Mickler agrees and realizes that, without Don Juan’s world, he can’t “breathe,” as Don Juan puts it.

The movie is a romantic fantasy although writer/director Jeremy Leven is careful to walk between reality and fantasy in order to let it be read either way: Don Juan could be Don Juan or he could just be a deluded kid. But as Kurt Vonnegut would put it, you are what you pretend to be. So fantasy or not, Don Juan is Don Juan as long as he believes it.

The movie is a romantic fantasy although writer/director Jeremy Leven is careful to walk between reality and fantasy in order to let it be read either way: Don Juan could be Don Juan or he could just be a deluded kid. But as Kurt Vonnegut would put it, you are what you pretend to be. So fantasy or not, Don Juan is Don Juan as long as he believes it.

Just as Dr. Mickler is Don Octavio DeFlores, should he choose to believe it. As Don Juan says to one of the psychologists when he asks why Don Juan believes Dr. Mickler is Don Octavio, “Why do you think Don Octavio del Flores is Dr. Mickler?”