I think I’m one of the few people who doesn’t care much for Out of the Past. It may be that for me the closer a movie gets to film noir, the less it appeals to me. I can’t argue with any of the superlatives used to describe this one. But despite all it does right in terms of noir, I can’t get terribly enthused.

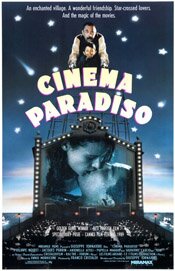

The strange love of movies – Cinema Paradiso

I last watched Cinema Paradiso about ten years ago. I’ve been meaning to watch it again for a long time but two things have held me back: the length (almost three hours — I don’t ever seem to have the time) and what I fear is a problem with my DVD copy. I hate the idea of getting halfway into a movie then finding a problem prevents me from seeing the rest.

But maybe this weekend I’ll overcome these hesitations. I really do want to see this again. For now, my impressions from when I saw it back around 2003 …

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Directed by Giuseppe Tornatore

My memory is poor, so I really don’t recall the original, theatrical version of Cinema Paradiso. Whether or not the longer version I have (the 2003 DVD release) is better, I’ve no idea. It adds 51 minutes to the film – a 174 minute movie compared to the theatrical release at 123.

This version of Cinema Paradiso is broken into three parts – the main character Salvatore as a child, a young man, and finally as an older man (middle-aged). It begins with a kind of prologue of Salvatore as the older man.

The beautiful opening shot is almost still, like a photograph. Slowly the camera pulls back as the opening credits roll. As we pull back, the image we have is truly a filmmaker’s image: it’s very deliberately staged and framed, and I think we’re supposed to be aware of this. It is still, as if frozen, somewhat like the memories of the character Salvatore.

As the camera continues back, we become aware that we’re looking through a window. Slowly retreating, at one moment it almost looks like a film screen.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

The current reality of this beginning (following the opening shot) establishes the kind of life Salvatore is living as a well-known filmmaker. It shows us a man avoiding his past. It gives us a man disconnected from his personal history and disconnected generally with the humanity around him. He’s isolated, and has chosen to be so.

The beginning also is what leads us into the story as it flashbacks to his life as a child, the film’s first section (following its prologue). It’s significant that we get into his childhood this way because it determines what we see and how we see it: it’s through the older Salvatore’s memory. It’s therefore not necessarily true in an objective sense.

This first part, Salvatore as a child (his memory of it), is generally brightly lit. It’s very open and spacious (compare the town square at the beginning of the film to the car-packed square at the end). In fact, everything here is open except for one thing: Alfredo’s little room in the Cinema Paradiso.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Like an image on film limited by the frames, his world is constrained by the walls of his projection room. But as the movie’s opening has shown us, and as demonstrated in Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, there is a world beyond the image’s frame (Tori’s mother in the movie’s opening). However much they may delight, or how real they may seem, movie’s are not everything. There is a world beyond them.

In the second part of the movie, Salvatore begins to become like Alfredo, at least this is a choice he is presented with. He takes over the projection booth. But he does have a choice and this is what the second part concerns.

While isolated in the projection booth, he also has a foot in the more tactile and chaotic world of the audience. This is through his relationship with the young woman Elena. In this part of the film, director Guiseppe Tornatore introduces a sexual element – in the films seen in the Cinema Paradiso, in the behavior of the boys of Salvatore’s age, and in Salvatore’s relationship with Elena, though this latter is more romantic in its treatment than sexual.

But the purpose of the sexuality is its relationship to romance and personal connections. It is something that pulls Salvatore away from the isolated world of films into the community of the audience, the town.

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

Salvatore’s relationship with Elena no longer a possibility, he now leaves the town (the audience). Alfredo not only supports this decision, he prompts it. He tells Salvatore, “You have to go away for a long time, many years, before you can come back and find your people.”

It’s ironic that Alfredo says this as he has never gone away, at least not physically. It could, however, be argued he has left emotionally and spiritually and has yet to return.

This leads to the film’s third part, the movie’s “now.” The older Salvatore finally returns to the town of Giancaldo. He returns for Alfredo’s funeral (who, in a sense, is finally “going away”). For Salvatore, the return is a series of revelations. As he says himself, he has been afraid to return.

One of his biggest discoveries is of Alfredo’s manipulations to keep Salvatore and Elena apart. She did not betray Salvatore, nor he her. It was Alfredo. His reasons were to force Salvatore out to his career as an artist, a famous filmmaker.

The other revelation is the film’s conclusion where Salvatore sits alone in the theatre watching Alfredo’s final gift, a reel of film. It is all the kisses and other intimate moments of human relationships the priest had removed from the movies. It is as if Alfredo is trying to return the part of life he had removed from Alfredo.

In contrast to the film’s beginning, this final section is visually darker and cramped. It is the real part of the film, as opposed to the remembered.

In this final part, we also see the destruction of the theatre, the Cinema Paradiso. While not the destruction of movies, it seems it’s the destruction of the tyranny of fantasy. While painful, it frees Salvatore from the confines imposed by images. It frees him of the prison art imposes and allows him back into life. We see a shot of young people laughing with a youthful sense of fun as they see the destruction of the building. It’s as if the present is clearing away the past so it can live.

The film appears to have two meanings, or at least two intents. In part, it is a loving homage to cinema and what it gives us. At the same time, it is also about the tyranny of art, at least for the artist. It is about what is denied him or her in order to pursue their art. It seems to say, as an artist you can observe life but you cannot be a part of it. You must remain a step removed. And movies are not real. They are moments; they are memories.

I think the film, at least in its extended version, is less a film about a love of cinema than a film about the sacrifices demanded by art. And while it does not provide an answer, I think it also speculates on the relationship between life and art and which has greater value.

How Chandler’s Marlowe is like Hamlet

Inexplicably, after what seems a kind of cinematic hiatus, I’m watching a bevy of older films and, to the dismay of some, rambling on paper (or screen, to be more accurate) my dimly lit opinions of what I’m seeing. I seem to be bouncing back and forth between noir and romantic comedies. The only thing I can venture as at least an explanation in part is this: I find watching movies relaxing, even meditative in some way. I don’t get this watching TV; only movies.

The other day, it was yet another noir …

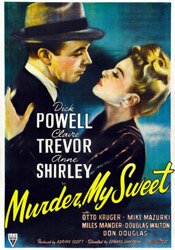

Murder, My Sweet (1944)

Murder, My Sweet (1944)

Directed by Edward Dmytryk

This murder mystery is, for me, itself a mystery in that I cannot fathom why they would change the title of Raymond Chandler’s book, Farewell, My Lovely to the far less subtle, Murder, My Sweet. I know it had something to do with not wanting to confuse the public with lead actor Dick Powell’s previous roles as a kind of song and dance man, but that doesn’t seem a very credible reason to me.

I suppose it’s not very important in the larger scheme of things, but it makes me shake my head. As for the movie …

When you go over reviews of this movie, as well as other movies based on Chandler’s books, you see one topic continually pop up: who was the best Philip Marlowe? It is probably not surprising to find there is not a great deal of consensus.

It strikes me that Marlowe is a kind of variation on Hamlet in that everyone has to play him, or a variation on him, and we decide who does it well, who doesn’t, and who’s Marlowe we buy into. On the DVD case cover, it tells us Dick Powell, who plays Marlowe in Murder, My Sweet, was author Raymond Chandler’s favourite. Of course, others have different opinions. Bogie comes to mind.

For many people Humphrey Bogart (The Big Sleep) is the Philip Marlowe. But just today I came across a review where the writer was claiming the best Marlowe was Robert Mitchum in 1975’s Farewell, My Lovely.

For many people Humphrey Bogart (The Big Sleep) is the Philip Marlowe. But just today I came across a review where the writer was claiming the best Marlowe was Robert Mitchum in 1975’s Farewell, My Lovely.

I admit that when I first saw Murder, My Sweet a few years ago Powell bothered me, but that had less to do with his performance than the fact I had Bogie so drilled into my head, from The Big Sleep but also similar characters, like Sam Spade from the The Maltese Falcon.

But I watched Murder, My Sweet again last night and I liked Powell much more. His gestures and speech fit the character nicely and he seems very natural as Marlowe. And the more I think about it, the more I think, “Yes, I like Powell’s Marlowe.” (That’s sort of like saying, “I like Plummer’s Hamlet.”)

As for the movie as a movie … It has a lot of what you would expect from a film of this kind: a lot of uncertainty as characters appear to be good, then bad, then good again, and then bad once more. Marlowe seems to think one thing then it’s shown he was only pretending, although a later scene shows he actually does think and feel that way.

In other words, the movie twists quite a bit and in many cases the twists are arbitrary for the sake of being a twist and to sustain the mood. But they don’t make a lot of sense. Yet in a film noir, you can often get away with that because the movie is less about plot and more about atmosphere, characters, character relationships … and lighting and camera focus.

In other words, the movie twists quite a bit and in many cases the twists are arbitrary for the sake of being a twist and to sustain the mood. But they don’t make a lot of sense. Yet in a film noir, you can often get away with that because the movie is less about plot and more about atmosphere, characters, character relationships … and lighting and camera focus.

I’ve read the book this movie is based on but don’t recall it, so I can only assume the movie stays roughly true to it and, if that’s he case, the filmmakers can thank Chandler for writing them an opening that is a nicely baited hook.

Told almost entirely in flashback by Marlowe, it begins with him in a police station being questioned and telling his story. That wouldn’t be much except we’re shown that he can’t see; his eyes are completely bandaged up. So as he’s is grilled and finally starts telling his story, we’re already hooked on the mystery of what happened to his eyes even before we’ve had an inkling of the real mystery.

Being film noir, we also get a femme fatale. Claire Trevor is Mrs. Helen Grayle, aka Velma. Director Edward Dmytryk introduces her to us legs first, underlining the character’s sexual nature and involvement with the story. But the there is also Anne Shirley as Ann Grayle, step-daughter and enemy of the second Mrs. Grayle (Velma). It’s easy to see why.

Being film noir, we also get a femme fatale. Claire Trevor is Mrs. Helen Grayle, aka Velma. Director Edward Dmytryk introduces her to us legs first, underlining the character’s sexual nature and involvement with the story. But the there is also Anne Shirley as Ann Grayle, step-daughter and enemy of the second Mrs. Grayle (Velma). It’s easy to see why.

Ann Grayle loves her father (Miles Mander), who is much older than his new wife. He also seems frail by comparison to everyone else in the film, even impotent. And he’s married to a woman who doesn’t appear to cover up what she’s interested in:

Helen Grayle: I find men very attractive.

Philip Marlowe: I imagine they meet you halfway.

But the movie isn’t just about this. It begins with a man named Moose (Mike Mazurki), who is just out of jail and looking for his Velma.

But the movie isn’t just about this. It begins with a man named Moose (Mike Mazurki), who is just out of jail and looking for his Velma.

Chandler books, and movies of this variety, are peppered with characters, most of whom are types, and give the storyline places to go and people to engage with as well as scenes to play out before getting to an end.

I liked how this one plays out. I like Dick Powell as Philip Marlowe and Claire Trevor as a femme fatale. And I’m pretty sure I’ll be watching this one again.

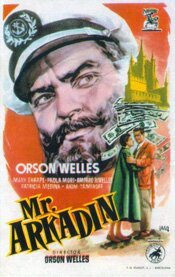

Mr. Arkadin – another fine mess

I’ve noticed Orson Welles had a thing for looking with slightly bowed head up from under his eyebrows. He uses it a lot in Mr. Arkadin, though I suspect it’s deliberate with an intention of parody, perhaps of himself. It’s hard to know with any certainty what his intentions were with that movie since it is an incomplete and irresistible mess.

Mr. Arkadin (1955), aka Confidential Report

Mr. Arkadin (1955), aka Confidential Report

Sometimes too much is too much and with Orson Welles’ Mr. Arkadin we have an good example of this. It’s too much of so many things (which in some ways is the film’s point, if it has one at all). To begin with, I have the Criterion 3-disc set, which means I don’t just have the movie; I have three versions of it.

The result has been that it has been sitting on my shelf for ages because I couldn’t decide which version to watch. I finally have arbitrarily choosen the second (or Confidential Report) version for no reason other than that I read somewhere that it was the one with the best picture quality.

If you know anything about Mr. Arkadin then you know it is a movie Welles never finished, so there is no definitive version. The movie was taken from him and others have completed it, in one fashion or another, over the years. The most recent version is the Criterion “comprehensive” version, a scholarly approach to restoring the movie in order to get a version as close to what we dimly know Welles was attempting, though no one really knows. (This last version is also the longest coming in at roughly 110 minutes.)

Not only do the various versions include and/or exclude various scenes, the sequence of the scenes also varies depending on the version. It was always intended to use flashbacks and a degree of disorientation for the audience, but the degree changes. The Confidential Report version may be the one that comes closest to being comprehensible, but that is open to debate.

Not only do the various versions include and/or exclude various scenes, the sequence of the scenes also varies depending on the version. It was always intended to use flashbacks and a degree of disorientation for the audience, but the degree changes. The Confidential Report version may be the one that comes closest to being comprehensible, but that is open to debate.

All of that aside, we’re still left with a movie to watch – one of its versions, at least. What’s the word on that? Is it any good?

Not really. It’s a mess, actually. I had thought I had never seen the movie previously but almost as soon as it started a voice in my head said, “Oh, that movie …” I had seen it before; it didn’t have much impact, largely because it isn’t a good movie.

It is, however, a fascinating movie, at least if Orson Welles intrigues you. It’s hard to know just how serious Welles was in making this work. There is a high level of playfulness in the movie. Is it because he’s just having fun, mocking himself even, but not too serious about the production? Or is it an aspect of a serious film?

It is, however, a fascinating movie, at least if Orson Welles intrigues you. It’s hard to know just how serious Welles was in making this work. There is a high level of playfulness in the movie. Is it because he’s just having fun, mocking himself even, but not too serious about the production? Or is it an aspect of a serious film?

Mr. Arkadin is, in some ways, almost a parody of Citizen Kane with its story of a mysterious, powerful man and the puzzle the movie creates around his identity.

Amongst other things, Welles distorts himself physically, at least in a sense, with his wig and fake beard and the obviousness of them, as well as his clothes in the movie. It’s as if he is deliberately focusing in on himself for the purpose of self-mockery. Was that the intent?

As for the puzzle the movie creates, that is largely responsible for the mess that the movie is as it tries to both resolve itself and remain oblique at the same time. Compounding this problem is fact that a puzzle, to be a real puzzle, must have a way to resolve. I suspect neither Welles nor anyone else ever truly figured that one out. As a result, the movie flounders in confusion because there really isn’t anywhere for it to go other than down another blind alley.

Yet the movie is dazzling in its confusion. And bizarre. Odd camera angles, over-dubbed dialogue (that changes from version to version), mix and match scenes … Yes, very odd.

I hadn’t planned to, but I watched Mr. Arkadin a day or two after having watched another of Welles’ movies, The Stranger. They make for an interesting contrast. The latter film is one Welles thought least highly of. It was an exercise in proving he could make a commercial film and, as a result, may be his most coherent. Mr. Arkadin is the exact opposite. It’s famously incoherent.

But for something that is a mess, it sure has style and humour and some fabulous scenes.