Call it a tall tale, a shaggy dog story or any of the other variations, this is a movie that uses exaggeration and fable to tell a story that centres around another romantic tall tale. And it works much better now, ten or more years later, with distance from the marketing and celebrity media atmosphere that surrounded it when released.

Subversive Preston Sturges and Morgan’s Creek

Eddie Bracken just looks funny. It’s not in a physically distorted way; it has something to do with the innocent, cherubic quality of his face that makes you smile. And when he starts moving? You start to laugh.

Film noir means B-movies like The Hot Spot

The Final Day of For the Love of Film (Noir) — Please or use the button on the right. If you’ve considered it but have put it off, now is the time. If you are interested in boatloads of great links to musings on film noir and its films, scroll down the page at Self-Styled Siren or over at Ferdy on Films. This is wonderful material!

Best known as an actor, Dennis Hopper also directed movies — eight, I believe, including the well known Easy Rider. Hopper never set the world alight as a director, but in 1990 he made a pretty good film noir called The Hot Spot. (The movie’s poster does a bit of over-selling with the words, “Film noir like you’ve never seen.”)

It’s a good example of a certain kind of neo-noir. As a genre, noir returns again and again because it tells a certain kind of story in a certain way. In The Hot Spot, you sense this is why Hopper is doing a film noir. On the other hand, you can see a neo-noir like the Coens’ The Man Who Wasn’t There and view a film that chooses the genre for the same reason but also for its style — in the Coen’s case, it’s a puzzling mix of homage and parody.

The Hot Spot is really just about its story: corruption. It’s not a great movie; it’s average. Still, it’s engaging and in some ways more true to noir for that reason (and what I assume was likely a comparatively small budget). It’s made as a B-movie and looks and feels like a B-movie. Here’s the review I wrote of it about ten or so years ago. ( There may be spoilers ahead, explicit and implicit.)

The Hot Spot (1990)

Directed by Dennis Hopper

“I found my level. And I’m livin’ it.”

This is a pretty good film noir from 1990 directed by Dennis Hopper. For some reason The Hot Spot seems to dwell in the undeserved province of obscurity. Yet it has all the noir elements, presents them well, and resolves itself in a fashion that would please Alfred Hitchcock.

It stars Don Johnson as a drifter – we never learn much about who he is, his past, or much background to support his motivation. But this doesn’t matter; in fact, it actually works for the film since it helps create a sense of mystery.

It also leaves you never quite sure about whether he’s a good guy or a bad guy.

He wanders into a sweltering “nothing-ever-happens-here” small town to get his car repaired then takes a job as a car salesmen as he waits. While waiting, he also checks out the lay of the land. What he finds is a dull town anxious for something, anything, to happen.

It’s the tedium of the town that has generated its odor of corruption and you can’t help feeling that the catalyst behind all the avarice and moral decay is simply boredom.

While in the town, Johnson’s character sees what appears to be an easy opportunity to rob the local bank and, seeing this, he immediately begins planning to do so. Script, acting and direction work well here as it is never explicitly stated that this is what he is planning; it’s communicated through selected shots, angles, and facial expressions. In fact, while you suspect this may be what he is up to you are never quite sure.

The other two principle characters in the film are Virginia Madsen as a slatternly, greedy wife and Jennifer Connelly as a young, innocent woman who is being blackmailed (despite the apparent contradiction in that).

Compounding the problems for Johnson’s character are the relationships he forms with these women. It reflects the conflict within Johnson’s character between doing what is right and doing what is wrong: in Madsen, he recognizes a similarly corrupt soul and while he is attracted to her he is also repelled. It is as if he sees himself in her and it generates a kind of self-contempt that he expresses through his contempt of her.

In Connelly’s character, he sees what he has lost and wants to get back: a sense of innocence and goodness. Through her, he sees the man he would like to be (as opposed to Madsen’s character which shows him what he feels he is and wants to leave behind). This is the essential conflict in the story, a moral one. It drives the story. Which way will Johnson’s character ultimately go?

The story and Hopper’s directing lay a seamy, sultry tone over the entire film. It is sexy in a sluttish way; an air of corruption hangs over everything. With the exception of Connelly’s character, everyone is an aspect of moral decay. Everyone is motivated by base interests, even Johnson’s character though he is the only one struggling with it.

While not stylish in the way the Coen’s The Man Who Wasn’t There is, The Hot Spot is probably a better example of noir. (This doesn’t mean it is a better movie; just a better example.) It is better in the sense that where the noir feeling in the Coen’s film is communicated through angles, lighting and other technical and stylistic elements, in Hopper’s film it is the story, characters and performance that make this noir. It’s not a brilliant film by any means, but it is damn good. Where a movie like The Man Who Wasn’t There looks like film noir, The Hot Spot feels noir – and that is what noir is. Feeling. Mood.

If I have a quibble with the movie it would be it’s length. It probably should have trimmed about 20 or 30 minutes. After all, most of the film noirs that originated the genre ran between 70 and 90 minutes.

(By the way, there are no points for the movie’s title. It’s pretty unimaginative. It’s also the same title I Wake Up Screaming would have had if the studios had had their way. Fortunately, the actors objected and they went with the original title.)

Dark Passage: a waste of Bogie and Bacall?

I just did some housecleaning on Piddleville. I more or less cleaned up some code and design on a few reviews that were in a very old Piddleville format.

While doing so, I came across a few Bogie and Bacall movies, including 1947’s Dark Passage which, as it turns out, I apparently didn’t care for. Here’s the review:

Dark Passage

Directed by Delmer Daves

Of the four movies Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall made together, Dark Passage is easily the weakest. (Their other movies together were To Have and Have Not, The Big Sleep, and Key Largo.) It’s a film noir that has what it thinks is a neat idea — the first third of the movie uses a “first-person” camera, meaning the central character is the camera viewpoint. But it falls flat.

Of the four movies Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall made together, Dark Passage is easily the weakest. (Their other movies together were To Have and Have Not, The Big Sleep, and Key Largo.) It’s a film noir that has what it thinks is a neat idea — the first third of the movie uses a “first-person” camera, meaning the central character is the camera viewpoint. But it falls flat.

In fact, the gimmick pretty much ruins the film because we don’t get to see (and therefore connect with) Humphrey Bogart’s character. In the first third, we don’t see him period. He is the camera viewpoint. In the second third, his head is bandaged (due to plastic surgery to alter his identity).

We don’t actually see Bogie till a large chunk of the movie is over. By the time we do, we’re bored.

Bogart plays a character wrongly accused and convicted of murder. The movie opens with his escape. On the run, he is rescued by Lauren Bacall’s character. (Everyone Bogart runs into in the movie conveniently has some connection to the story.)

Bogart plays a character wrongly accused and convicted of murder. The movie opens with his escape. On the run, he is rescued by Lauren Bacall’s character. (Everyone Bogart runs into in the movie conveniently has some connection to the story.)

A helpful cab driver later recommends a shady plastic surgeon to Bogart’s character. Bogart gets his face changed then goes off in search of the criminals who framed him so he can prove his innocence.

Despite trying, the movie never gets very interesting. For one thing, there is very little to relieve the darkness of the noir approach. There is also little chemistry between Bogart and Bacall and this is largely because they play so few scenes together, at least in the first two thirds.

The characters do have scenes, but since Bogart isn’t physically in them (because of the camera viewpoint or because his head is wrapped in bandages and he can’t talk), the Bogie-Bacall magic is absent.

The other problem are the improbable conveniences mentioned above — the helpful cab driver, a guy who picks up Bogart when he is hitchhiking, Bacall’s appearance. It’s all a little too improbable.

The only time we get a sense for an interesting story is at the very end when Bogart and Bacall have fled to South America. Suddenly the heavy handed noir atmosphere is relieved and we get something that has more of the atmosphere of Casablanca or To Have and Have Not.

It seems clear that the movie has misread what made Bogart and Bacall so interesting together. It certainly misreads Bogart.

Despite the success of movies like The Big Sleep and The Maltese Falcon, it wasn’t the noir genre that made Bogart popular. It was that he was playing a flawed romantic hero within them.

In Dark Passage he simply plays a schmuck floundering around trying to prove his innocence. He doesn’t play a strong character. If anything, the character is rather weak.

And so we end up with a tedious movie, one that relies on a gimmick rather than the power Bogart and Bacall could bring to the screen.

They are wasted in this movie.

On Amazon:

- Dark Passage

- Bogie and Bacall – The Signature Collection (includes: The Big Sleep, Dark Passage, Key Largo and To Have and Have Not)

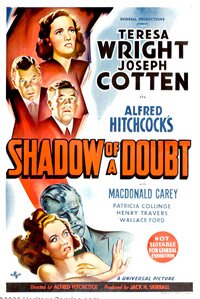

20 Movies: Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

A list of movies that didn’t include Alfred Hitchcock wouldn’t be much of a list. One of my favourites, and one I think it’s time I watched again, is Shadow of a Doubt, with a very creepy Uncle Charlie played by Joseph Cotten.

As mentioned in the review below, in many ways Hitch is the dark twin of Frank Capra. What the angel Clarence was to Bedford Falls, Uncle Charlie is to Santa Rosa. Only inside out.

Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

Shadow of a Doubt (1943)

directed by Alfred Hitchcock

It’s claimed by many that Shadow of a Doubt was Alfred Hitchcock’s favourite of all the films he had made; some say he considered it his best. The claim rings true if you’re even modestly familiar with his films, his preoccupations and his humour. You can understand how the story would delight him.

Shadow of a Doubt presents us with an almost quintessential American town of the 1940’s. It’s almost Capra-esque. In a way, Shadow of a Doubt is George Bailey’s Bedford Falls from It’s a Wonderful Life except where Capra brings an angel to it, Hitchcock brings the devil.

His name is Uncle Charlie and he’s played by Joseph Cotten with delicious charm that alternates with brooding self-obsession.

Into the charmed and innocent life of California’s little Santa Rosa, into the home of the all-American family of the Newtons, comes Mom’s little brother, Uncle Charlie, for a visit of no determined length. He’s welcomed with cheerful enthusiasm by his sister Emma (Patricia Collinge), and by his namesake niece Young Charlie (Teresa Wright).

Unfortunately, no one is aware that Uncle Charlie, pleasant as he seems, is a psychopathic killer, a man who behind his charm hates the world and everyone in it.

Unfortunately, no one is aware that Uncle Charlie, pleasant as he seems, is a psychopathic killer, a man who behind his charm hates the world and everyone in it.

Uncle Charlie’s secret view of the world is important as it’s in direct contrast with the Newton view, especially Young Charlie’s. Cotton’s character represents corruption; Wright’s represents innocence. The film can broadly be seen as a loss of innocence.

As the film opens, we meet Uncle Charlie and immediately become aware that he has a dark secret. Two men are after him, though we’re not sure who they are (I think we assume it’s the police though we’re not told this right away). Charlie is on the run but we don’t know why.

He escapes and goes to his sister’s family in Santa Rosa. When he arrives by train Hitchcock visually telegraphs what is about to happen. It’s a bright, sunny day and the family run down the platform to meet the train. The youngest child of the Newton’s is isolated for a moment on the platform, in the sun. As the train pulls up it’s dark shadow moves along the platform engulfing the child.

We then seen an apparently weak and ill Charlie get off the train. He’s bent over and almost hobbles. But as he sees the Newtons his face changes, he puts on a facade of charm, straightens up and in an instant is the picture of happy health.

We then seen an apparently weak and ill Charlie get off the train. He’s bent over and almost hobbles. But as he sees the Newtons his face changes, he puts on a facade of charm, straightens up and in an instant is the picture of happy health.

Alone, Charlie is quiet and brooding. Amongst others, he’s vibrant and witty. Only every now and then does he reveal himself publicly. When he does, he quickly covers for his mistake.

Within the family, Teresa Wright’s Young Charlie is easily the brightest, most perceptive member. Although she hero-worships Uncle Charlie, she quickly sees there is something about him that isn’t right. But because she loves her uncle the way she does, she won’t admit to herself the truth about her uncle.

The law catches up with Uncle Charlie, however, and soon Young Charlie is enlisted by the police to help them catch him. Uncle Charlie then discovers his niece knows his secret, or at least that she’s aware he has one, and has to deal with this threat to himself.

The law catches up with Uncle Charlie, however, and soon Young Charlie is enlisted by the police to help them catch him. Uncle Charlie then discovers his niece knows his secret, or at least that she’s aware he has one, and has to deal with this threat to himself.

The contest soon becomes one between Uncle Charlie and his niece and the suspense builds to its crescendo – all very Alfred Hitchcock like.

It’s a perfect Hitchcock film. It’s easily one of the best and an argument could be made for it being the best. Shadow of a Doubt is not sensational in the way of movies like Psycho or The Birds. It’s subtler and quieter and in some ways more menacing because of this.

It evokes idyllic America then slowly peals back its layers to reveal a darkness beneath. (This is wonderfully illustrated when the two Charlie’s step off the Norman Rockwell main street into the smokey bar and meet the bored, defeated waitress – a kind of dark opposite of Young Charlie.)

It evokes idyllic America then slowly peals back its layers to reveal a darkness beneath. (This is wonderfully illustrated when the two Charlie’s step off the Norman Rockwell main street into the smokey bar and meet the bored, defeated waitress – a kind of dark opposite of Young Charlie.)

The DVD of Shadow of a Doubt is pretty good but certainly not flawless. There is some scratching and a few awkward jumps, though nothing alarming. The image, however, is pretty solid and the sound is good for a film of this period. The disc also has Beyond Doubt: The Making of Hitchcock’s Favorite Film, an informative feature that includes the thoughts of Teresa Wright, Hume Cronyn and Peter Bogdanovich among others.

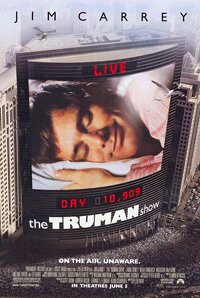

20 Movies: The Truman Show (1998)

An innocent abroad in a less-than-innocent world is a standard story template. It has been used over and over. Decades ago I read Robert Heinlein’s A Stranger in a Strange Land. That was one take on the innocent story. Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, with his main character of Billy Pilgrim, was another.

An innocent abroad in a less-than-innocent world is a standard story template. It has been used over and over. Decades ago I read Robert Heinlein’s A Stranger in a Strange Land. That was one take on the innocent story. Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five, with his main character of Billy Pilgrim, was another.

It shows up in movies frequently as well, such as The Truman Show. When it is used, it is often with a satirical purpose. Through the innocent’s eyes, we see how the world really is (or how the author or filmmaker thinks it really is). It’s usually comic, at least to some degree.

But the satire isn’t just intended to illustrate what is wrong with the world. It is also to illustrate what could be right and how we’ve gone off track from pursuing it.

That is really what is at the heart of The Truman Show. It isn’t about the misguided nature of television and its audiences, though it is that in part. And it’s not simply about the hazards of over-the-top commercialism, though it’s about that too.

The story of the innocent is really about what the point of our lives is and what we could be doing with them.

Truman’s story is about a man who wants more. Not more “stuff,” but more meaning. Yes, his life is comfortable. But for Truman, that’s not enough. He wants to know, “What else is out there?”

The Truman Show (1998)

directed by Peter Weir

directed by Peter Weir

“You never had a camera in my head.”

Those words, I think, capture the essence of The Truman Show best. There’s much in the world that can be controlled, but controlling what someone thinks and, maybe more importantly, feels is not so easy.

For me, this is one of the best movies of the 1990’s, and one of my favourite movies, period. Now, with the recent release of it in a special edition, I have the DVD I had been wanting – better image, informative features. (Note: this review was written in 2005 and refers to the Special Collector’s Edition DVD.)

Slightly preceding the current glut of reality TV shows, the film’s concept seems simple enough, though perhaps less clever now than when it first appeared, before our reality TV world.

While the concept may seem simple – a movie about a guy whose entire life is broadcast live on television – imagine how you would execute that and make it interesting. It comes across more like a clever notion on paper, but the kind of thing that could lead you into a cinematic fiasco.

While the concept may seem simple – a movie about a guy whose entire life is broadcast live on television – imagine how you would execute that and make it interesting. It comes across more like a clever notion on paper, but the kind of thing that could lead you into a cinematic fiasco.

But between Andrew Niccols’ script, Peter Weir’s direction and some great casting, it works brilliantly.

Jim Carrey is Truman Burbank. His life , from birth, has been broadcast live to the world (unbeknownst to him). He lives in a town called Seahaven – always has, he’s never left – but what he doesn’t know is Seahaven is a television set in California, not a town on the Florida coast. He lives in a not-quite-perfectly controlled world.

“We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented,” says Christoff (Ed Harris), the show’s creator and mastermind.

“We accept the reality of the world with which we are presented,” says Christoff (Ed Harris), the show’s creator and mastermind.

But as much as Christoff controls Truman’s world, he can’t control everything – including Truman.

There are small errors in Truman’s world and they might go unnoticed by him except the life scripted for him is not the one he would live. The more the show’s creator, actors and crew try to steer Truman and keep him on script, the more he resists.

And so Truman embarks on discovering his world, though that’s not his initial motivation.

As mentioned in the special features, Peter Weir made one change to the script that was bang on the money. Originally set in New York, and a darker film, Weir understood that for people to watch such a show (not the movie, but in the script’s world, The Truman Show), it would need to be lighter, more comforting.

So the movie is set in Seahaven, a somewhat heightened reality. It’s roots are more in the world of 1950’s television than the real world, though not to such an extent that it lacks credibility.

Another great notion in the film’s making was the casting of Carrey. He is perfect as Truman. Charismatic and affable, he brings the right amount of innocence to the role of Truman. It might not have worked in another movie, but in the world of The Truman Show it hits the mark.

I also like that there are several ways of seeing The Truman Show. There is the obvious satire on television culture and the issue of personal freedom.

(I like the irony of Christoff “a very private man” being the architect of a very public life – Truman’s.)

Another way of seeing the film, however, is as a fable of a child leaving home.

Christoff is an obvious father figure and Truman is clearly a young man trying his damnedest to leave and find his own life – but not the one Christoff dreams for him (rather like a parent trying to impose his vision on his child.)

In fact, however you view the film, it’s essentially a fable. Perhaps this is why I like the movie so much – I’ve a weakness for these types of films when they are well done.

In fact, however you view the film, it’s essentially a fable. Perhaps this is why I like the movie so much – I’ve a weakness for these types of films when they are well done.

Weakness or not, I consider this one of the best films of the last decade or so. It’s also one I think will continue to be watched over the years as it captures, quite succinctly and in an engaging fashion, something in the nature of freedom that is deeply woven into the human fabric. The film’s ending captures an archetypal, mythic moment and it’s one that resonates. I can’t recommend this one highly enough.

The Truman Show (the trailer)

Links:

- The Truman Show – DVD, HD, etc. on Amazon.com (U.S.)

- The Truman Show – DVD, HD, etc. on Amazon.ca (Canada)