At the end of this I make an admission — but why wait? I prefer Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison to the better known The African Queen, two movies from the same director (John Huston) and superficially similar. I like this movie and always have. But be warned! It’s a quiet one; it’s characterized by restraint.

Errol Flynn loses a step, gains some gravity

No snide comment is implied by “Errol Flynn … gains some gravity,” though by the time this movie was made the older Flynn had put on a few pounds. Rather, his performance has a bit of weight that wasn’t there in the younger Flynn’s roles. You can see it in this movie, The Master of Ballantrae, though I don’t think anyone would rate the movie itself terribly high.

The curious hybrid called Deep Impact

When is a disaster movie not a disaster movie (even though it’s a disaster movie)? The answer is when it’s a Mimi Leder directed disaster movie and the usual trappings of the genre are downplayed and others, usually dealt with in an offhand manner, are lingered over.

American Rebel: Eastwood bio a disappointing read

While I remember the song from Rawhide I don’t recall ever having seen it. For me, Clint Eastwood’s career would have begun with A Fistful of Dollars (1964).

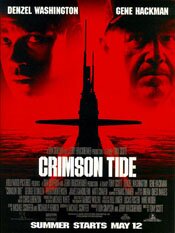

Characters in close quarters – Crimson Tide

You wouldn’t immediately associate submarine movies with a film like Key Largo but they have something in common. The dramatic tension comes about by having characters constrained within close quarters. In Key Largo, it’s within a hotel because of a hurricane; in submarine movies it’s due to the nature of submarines.

I don’t like a phrase like “submarine movies” but there is no getting around the fact there is a kind of sub-category of action-adventure films characterized by where they are set — on submarines. They’re often among the best of the action-adventure variety of films because of the close quarters that seem to force filmmakers to concentrate on characters.

Crimson Tide (1995)

Crimson Tide (1995)

Directed by Tony Scott

In the tradition of movies like Run Silent, Run Deep, The Hunt for Red October and Das Boot, the Tony Scott directed Crimson Tide is submarine drama with strong lead characters. If it distinguishes itself from those previous movies it is by being faster moving and much noisier.

That may not sound overly appealing but it be would wrong to think that way. This is a very good, very engaging action-adventure with a strong foundation: the performances of Denzel Washington and Gene Hackman.

It’s also supported by strong performances by its supporting cast – Matt Craven, George Dzundza, Viggo Mortensen and James Gandolfini, to name a few.

Without its strong cast, I think this would likely be just an average film but with them it is firmly anchored.

There is a state civil war in Russia. Rebel generals have taken over a base with nuclear weapons and it appears as if they may use them. The U.S. naval sub Alabama, nuclear-armed, is sent to Asian waters to await instructions. They get them: prepare your missiles. A further message, only partially received, may be orders to fire them or to stand down. It is unclear.

The movie’s conflict is between the sub’s captain (Gene Hackman) and its new executive officer (Denzel Washington). For the missiles to be fired, the two must be in agreement. They aren’t. The captain wants to fire; his second in command does not.

What makes movies like this dramatic and appealing (and you see this in films like Run Silent and Red October) is that the “bad guy” is external – off set. The leads, in this case Hackman and Washington, are both good guys but they are at opposing ends about what to do and thus in conflict.

This increases the film’s conflict by removing the easy, black and white choice and while an audiences’ sympathy may align with one, they can’t easily dismiss the other.

This is also reflected in the unfolding of the film’s drama where the sub’s crew must choose sides, many of whom are conflicted (like Mortensen’s Lt. Ince). We end up with struggles in the submarine, including mutiny, because of the lack of clarity. It’s all due to the ambiguity of the last orders received.

The movie doesn’t ease its audience into the story; it throws them in head first. Music and editing thrum as it begins with a journalist describing events in Russia. There is no slow unfolding of exposition. Director Scott and producer Jerry Bruckheimer take the approach of throwing the audience in at full speed. Details fly by like rapid fire flash cards.

In some movies, this is noise and fury approach can be a gimmick to mask an uninspired story but in Crimson Tide it’s a quick and effective way to get quickly to what is an intelligent, well told story. Perhaps its due to the close quarters of submarines, but movies like this seem to lend themselves to dramatic, character-driven films.

While my own preference is for the quieter tension of a movie like The Hunt for Red October (which I find more effective), it works for Crimson Tide as it delivers a compelling film that leaves an audience with something to question and discuss when is over.

On the whole, this is a very good movie and well worth seeing and more than once.

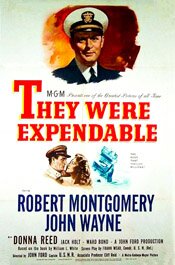

John Ford, John Wayne and Expendable

Sometimes the release dates of movies can be significant. Get it wrong and you’re all in a muddle, as I was when I watched They Were Expendable.

The movie itself isn’t anything I would say you should rush out to see unless you’re a really big John Ford and/or John Wayne fan. The tone of it is curious, however, given the kind of movie it is and what it is about. Some movies are intriguing despite not being great films and that is the case with this one.

They Were Expendable (1945)

They Were Expendable (1945)

Directed by John Ford

I was very confused when I watched the war movie They Were Expendable because I thought it was from 1941. It turns out that is when the movie is set as it opens. My confusion evaporated, however, when I realized it was from 1945, though it is still an unusual movie that John Ford gives us.

Believe me, with this movie the year really matters – especially if you confuse it with four years earlier.

This movie was released in December of 1945. In World War II, Japan formally surrendered in September of 1945.

The movie is somber recounting of the early days of the war for the U.S., beginning with the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941.

Made with the approval and assistance of the U.S. Navy, Army and Coast Guard, it shows us the U.S. getting its behind kicked by the Japanese – starting in Pearl Harbor and continuing through the Philippines.

Audiences at the time of the film’s release, however, would be fully and completely aware of the end result of it all – victory in the Pacific; Japan’s surrender.

The reason John Ford shows us all the bad news from the war’s early days is because he’s telling the story of the PT boats – how their role in the war came about (they weren’t highly regarded originally), how they won respect and the sacrifices made by the crews that worked them. (The tagline was, “A tribute to those who did so much… with so little!”) However, the main character is really the boat itself.

The movie is a solemn tribute and sober homage but also full of patriotism which, appropriate to the period of its release, may strike a current day viewer as a bit much.

There are good action scenes in the movie as well as some interesting, almost noir-ish lighting in others. The movie itself appears to be in poor shape, at least on the DVD copy I have. I don’t know if any restorative work went into it but it doesn’t appear so given the scratches in a number of scenes. I’m a bit surprised it comes to use from Warner Brothers. It may have something to do with the lack of good original film materials. I don’t know.

Overall, I can’t say this is a great movie. It’s a curious one, however. It’s worth seeing at least once, especially if you’re a fan of either John Ford or John Wayne. Just keep in mind this movie should probably be viewed as a propaganda work.

And maybe that is what makes it peculiar. It’s quite a bit of “Rah, rah!” about PT boats but seems to also want to be a solid drama and thus it acquires a bipolar quality.

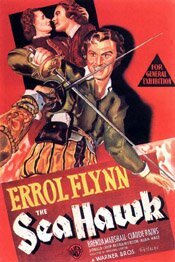

The impish Errol Flynn in a swashbuckler

A few years ago I bought a fistful of Errol Flynn movies that were in one of those many Warner Brothers collections. I had only vague memories of Flynn movies but was curious having seen The Adventures of Robin Hood and, a few years earlier, having read his autobiography, My Wicked, Wicked Ways (recommended, by the way — it is so much fun to read).

Among the movies in the collection was the one I scribbled about below, The Sea Hawk. Interestingly, just as Robin Hood was directed (in part) by Michael Curtiz, he also directs this movie. He seems to have been aware of what Flynn brought to these movies and was very good at getting it.

The Sea Hawk (1940)

The Sea Hawk (1940)

Directed by Michael Curtiz

I’m halfway through Errol Flynn: The Signature Collection and I think I’ve hit the real gem of the lot. (Not that the others aren’t good too.) It’s The Sea Hawk and it really does put the “swash” in swashbuckler.

It’s absolutely brilliant and in a number of respects. I can’t help comparing it to The Adventures of Robin Hood. It has much of the same feel while at the same time has a little something different.

For one thing, both films capture a sense of fun and exuberance. Both also manage to be rousing costume adventures without any sense of self-consciousness though The Sea Hawk differs slightly in that Errol Flynn plays the British pirate Captain Geoffrey Thorpe with a kind of very contained impishness.

His captain is apparently quite serious, patriotic and heroic, yet every now and then he seems to be restraining a smile or grin.

As someone in the special feature on the DVD says (The Sea Hawk: Flynn in Action), it’s almost as if Flynn is asking the audience, “Are you really buying this?”

But in these Flynn movies this kind of feeling is not one of mocking the audience but of having fun with them. Flynn seems to play his swashbuckling roles the way the early Springsteen played concerts – the more fun the audience had, the more fun he had and together they create a kind of synergistic relationship.

Another fascinating way in which The Adventures of Robin Hood and The Sea Hawk compare is in their look. Where Robin Hood is an incredibly exuberant display of colour, The Sea Hawk is nothing less than a magnificent example of black and white. (Although I could have done without the Panama scenes done in sepia.)

The sea battles between the ships are fabulous.

We know from recent films like Master and Commander that great sea battles can be done in colour but I’ll take The Sea Hawk’s scenes anytime. (It’s also incredible to think these were done on sets.)

There is also a great sword fight (as there must be to conclude an Errol Flynn swashbuckler) where, again, the black and white scenes with their use of light and shadow are exceptional. I loved the great shadows on the walls during the struggle.

The Sea Hawk is about as close to the quintessential swashbuckler as you can get. It has Errol Flynn, the man who pretty much defines the hero of such movies.

It has the great set pieces like the sea battles and the swordfights. And it has the music that has influenced the sound of almost all heroic adventures.

Credit for the music goes to Erich Wolfgang Korngold. His score (which is apparently not just rousing but quite clever as it uses, in part, themes from the earlier The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex but in a reworked form), is operatic which, if you think about it, is really what such romantic adventures require.

I really didn’t know a great deal about The Sea Hawk before watching it. And to be honest, I wasn’t expecting a great deal. I basically put it in the DVD player because I wanted to watch something and I hadn’t seen this one yet.

As often happens, when I was least expecting it, I encountered a wonderful movie. Highly recommended.

(The Sea Hawk also aired last night on TCM. I missed it but I may watch my copy again tonight. The above was written roughly about April 2005.)

Chess games and submarine movies

You might think that movies set on submarines are relatively rare. They are — relatively. But as a quick search online will show you (as it just showed me), there are actually quite a few of them. (Das Boot and Crimson Tide come to mind.) Relative to other movies, they may be rare. But there are quite a few of them nonetheless.

This leads me to the two movies I wanted to bring up: Run Silent, Run Deep (1958) and The Hunt for Red October (1990). I don’t know what the correct term for describing them would be — suspense, thriller, action? I lean toward suspense but what makes them compelling is a phrase Sean Connery’s character, Marko Ramius, uses in Red October: chess game.

This leads me to the two movies I wanted to bring up: Run Silent, Run Deep (1958) and The Hunt for Red October (1990). I don’t know what the correct term for describing them would be — suspense, thriller, action? I lean toward suspense but what makes them compelling is a phrase Sean Connery’s character, Marko Ramius, uses in Red October: chess game.

There is more actual “action,” as in torpedoes and so on, in Run Silent, Run Deep, but neither film has a great deal of it. It’s the drama of the situations and, again in both films, the mystery surrounding a lead character’s motives, Clark Gable’s in Run Silent and Sean Connery’s in Red October.

Both movies get more physically and visually dramatic with action in their final acts but for the most part these chess games are mysteries rather suspense thrillers, though both are suspenseful and, I suppose, thrilling.

However they are described, I like both movies quite a lot and have watched both many times. They are well worth seeing more than once ….

Run Silent, Run Deep (1958)

I saw an interview with the actor Laurence Fishburne the other day in which he was speaking of various influences when he was young. At one point, he brought up the movie Run Silent, Run Deep and Clark Gable. What struck him in the movie was Gable’s gravitas. I immediately thought, “Yes, that is the perfect word for it.” (Read more)

The Hunt for Red October (1990)

In the class of movies known as action-adventure, The Hunt for Red October stands out as one of the best and as one of the strangest because the action is relatively minimal and doesn’t play a huge role in generating the film’s suspense and tension. (Read more)

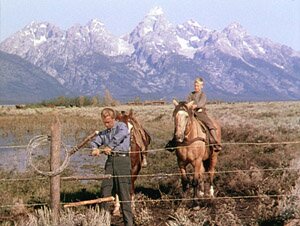

Is Shane too aware of itself as a western?

I wrote the bit below about 8 to 10 years ago after seeing Shane for the first time. It’s strictly a gut response and an attempt to figure out that gut response. But I think it may be time for me to re-watch this movie and see if I still have the same reaction or if I can finally see what many others see in the movie.

Shane (1953)

Shane (1953)

Directed by George Stevens

I’ve never seen Shane before. I haven’t discussed it in a film studies class. I haven’t spent hours in bars or cafes talking about it. I just like westerns, knew it was considered one of the best, and finally decided to watch it. So my reaction to it is, in many ways, fresh and not particularly tainted by what others think of it.

Gut response? I was a bit bored. But I’m not so sure it’s a fault of the movie so much as it’s a problem that the film’s sensibilities are of a time when they were not as frenetic as they are now. People were a bit more open to a more leisurely pace.

On the other hand, some of the problems were not just sensibility and the film’s tempo. Shane suffers, I think, from being a little too self-conscious. It’s a little too aware of the western genre, of its place in it, and of its purpose, which is too comment on the genre and film violence.

Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time.

Unfortunately for someone from my generation, the story of Shane is one we’re too familiar with from it’s recapitulations, especially the Clint Eastwood films like High Plains Drifter and Pale Rider. Alan Ladd as Shane, despite director George Stevens’ efforts, is a little too clean, a little too smooth shaven. He’s not harsh enough. I’m not sure this is a flaw with the film so much as it’s a flaw with seeing it from a distance in time.

Shane arrives at a Wyoming homestead as a drifter. He stays for a while with people who are oppressed by cattlemen trying to take over their land. He is distant but suggests strength. Men and women admire and respect him, children hero-worship him. Eventually troubles with the cattlemen come to a head and it is Shane who faces them down.

Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence.

Of course, there is a helluva lot more to it than that. But that’s the basic premise. It’s the western model Eastwood used many times. The film is self-consciously rooted in a myth and wants to comment on it. It especially wants to comment on violence.

The result is a lot of time spent on creating the non-violent world represented by Marion (Jean Arthur) and her husband-farmer played by Van Heflin. (He, by the way, is absolutely perfect in this role; his performance is nothing less than great.)

Unfortunately, the family life, the life of hard work, is not particularly interesting. To appreciate the value of this kind of life you have to live it. To watch it is to go to sleep.

We get to see Shane watching this life, and see his longing for it (an essential element in the film) but again, it’s a bit of a snooze. It’s one of the hardest tasks an artist can set him or herself: to make the lives of nice people interesting for an audience. It is seldom done successfully.

Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained.

Meanwhile, we are constantly aware that eventually Shane must draw his gun and the big showdown must come. But it takes forever. There are legitimate reasons for why it takes so long, and you can appreciate what George Stevens is trying to do, but … it takes so damn long! And the film is so restrained.

This is all just gut reaction but I really think Shane falls short primarily for one reason: it’s a movie for the intellect and not for the gonads. Westerns are meat-and-potatoes films. They are best when they’re simple. They’re best when they follow formulas. They are best when they tell you things that are true viscerally, not via the brain.

(Note: This review was written back around 2003. It was my initial response to my first viewing of the movie.)