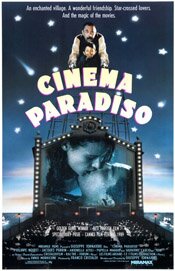

I last watched Cinema Paradiso about ten years ago. I’ve been meaning to watch it again for a long time but two things have held me back: the length (almost three hours — I don’t ever seem to have the time) and what I fear is a problem with my DVD copy. I hate the idea of getting halfway into a movie then finding a problem prevents me from seeing the rest.

But maybe this weekend I’ll overcome these hesitations. I really do want to see this again. For now, my impressions from when I saw it back around 2003 …

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Directed by Giuseppe Tornatore

My memory is poor, so I really don’t recall the original, theatrical version of Cinema Paradiso. Whether or not the longer version I have (the 2003 DVD release) is better, I’ve no idea. It adds 51 minutes to the film – a 174 minute movie compared to the theatrical release at 123.

This version of Cinema Paradiso is broken into three parts – the main character Salvatore as a child, a young man, and finally as an older man (middle-aged). It begins with a kind of prologue of Salvatore as the older man.

The beautiful opening shot is almost still, like a photograph. Slowly the camera pulls back as the opening credits roll. As we pull back, the image we have is truly a filmmaker’s image: it’s very deliberately staged and framed, and I think we’re supposed to be aware of this. It is still, as if frozen, somewhat like the memories of the character Salvatore.

As the camera continues back, we become aware that we’re looking through a window. Slowly retreating, at one moment it almost looks like a film screen.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

The current reality of this beginning (following the opening shot) establishes the kind of life Salvatore is living as a well-known filmmaker. It shows us a man avoiding his past. It gives us a man disconnected from his personal history and disconnected generally with the humanity around him. He’s isolated, and has chosen to be so.

The beginning also is what leads us into the story as it flashbacks to his life as a child, the film’s first section (following its prologue). It’s significant that we get into his childhood this way because it determines what we see and how we see it: it’s through the older Salvatore’s memory. It’s therefore not necessarily true in an objective sense.

This first part, Salvatore as a child (his memory of it), is generally brightly lit. It’s very open and spacious (compare the town square at the beginning of the film to the car-packed square at the end). In fact, everything here is open except for one thing: Alfredo’s little room in the Cinema Paradiso.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Like an image on film limited by the frames, his world is constrained by the walls of his projection room. But as the movie’s opening has shown us, and as demonstrated in Sergio Leone’s The Good, The Bad and the Ugly, there is a world beyond the image’s frame (Tori’s mother in the movie’s opening). However much they may delight, or how real they may seem, movie’s are not everything. There is a world beyond them.

In the second part of the movie, Salvatore begins to become like Alfredo, at least this is a choice he is presented with. He takes over the projection booth. But he does have a choice and this is what the second part concerns.

While isolated in the projection booth, he also has a foot in the more tactile and chaotic world of the audience. This is through his relationship with the young woman Elena. In this part of the film, director Guiseppe Tornatore introduces a sexual element – in the films seen in the Cinema Paradiso, in the behavior of the boys of Salvatore’s age, and in Salvatore’s relationship with Elena, though this latter is more romantic in its treatment than sexual.

But the purpose of the sexuality is its relationship to romance and personal connections. It is something that pulls Salvatore away from the isolated world of films into the community of the audience, the town.

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

Salvatore’s relationship with Elena no longer a possibility, he now leaves the town (the audience). Alfredo not only supports this decision, he prompts it. He tells Salvatore, “You have to go away for a long time, many years, before you can come back and find your people.”

It’s ironic that Alfredo says this as he has never gone away, at least not physically. It could, however, be argued he has left emotionally and spiritually and has yet to return.

This leads to the film’s third part, the movie’s “now.” The older Salvatore finally returns to the town of Giancaldo. He returns for Alfredo’s funeral (who, in a sense, is finally “going away”). For Salvatore, the return is a series of revelations. As he says himself, he has been afraid to return.

One of his biggest discoveries is of Alfredo’s manipulations to keep Salvatore and Elena apart. She did not betray Salvatore, nor he her. It was Alfredo. His reasons were to force Salvatore out to his career as an artist, a famous filmmaker.

The other revelation is the film’s conclusion where Salvatore sits alone in the theatre watching Alfredo’s final gift, a reel of film. It is all the kisses and other intimate moments of human relationships the priest had removed from the movies. It is as if Alfredo is trying to return the part of life he had removed from Alfredo.

In contrast to the film’s beginning, this final section is visually darker and cramped. It is the real part of the film, as opposed to the remembered.

In this final part, we also see the destruction of the theatre, the Cinema Paradiso. While not the destruction of movies, it seems it’s the destruction of the tyranny of fantasy. While painful, it frees Salvatore from the confines imposed by images. It frees him of the prison art imposes and allows him back into life. We see a shot of young people laughing with a youthful sense of fun as they see the destruction of the building. It’s as if the present is clearing away the past so it can live.

The film appears to have two meanings, or at least two intents. In part, it is a loving homage to cinema and what it gives us. At the same time, it is also about the tyranny of art, at least for the artist. It is about what is denied him or her in order to pursue their art. It seems to say, as an artist you can observe life but you cannot be a part of it. You must remain a step removed. And movies are not real. They are moments; they are memories.

I think the film, at least in its extended version, is less a film about a love of cinema than a film about the sacrifices demanded by art. And while it does not provide an answer, I think it also speculates on the relationship between life and art and which has greater value.

Stagecoach (1939)

Stagecoach (1939)

Crimson Tide (1995)

Crimson Tide (1995)

They Were Expendable (1945)

They Were Expendable (1945)

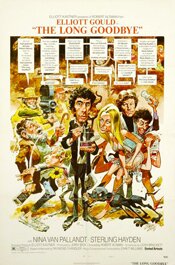

The Long Goodbye (1973)

The Long Goodbye (1973)

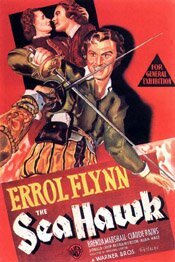

The Sea Hawk (1940)

The Sea Hawk (1940)

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

Cinema Paradiso (1988) But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life.

But once the credits are over and we’re at the furthest distance of the pull back, we see we’re in a room in a house. Dialogue begins and we see Salvatore’s mother move into the frame. The serene beauty of the opening shot, the staged nostalgic memory (which is what the opening has been) is disrupted by reality of everyday life. Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting.

Alfredo, the projectionist at the town of Giancaldo’s movie theatre, the Cinema Paradiso, and who is the key figure in Salvatore’s life, is seemingly imprisoned. With the exception of a few scenes, we almost always see him looking through his window on the square, looking through the small opening in the projection room on the theatre, or loading and unloading reels of film in his cramped projection room. His life is contained by these small confines. He is always an observer. He is never a part of the audience below him in the theatre who seem to be continually chattering and interacting. Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy.

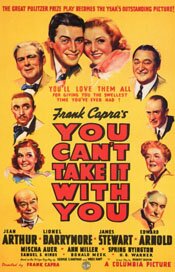

Alfredo, knowing this, and sensing the cinematic artist in Salvatore, undermines the relationship between Salvatore and Elena. This action parallels that of the town’s priest who in the first part of the film had been ordering the censoring of all the scenes involving kisses, scenes that suggested intimacy. You Can’t Take It With You (1938)

You Can’t Take It With You (1938) Everyone in the family follows his credo – they all do whatever makes them happy. The household is therefore chaotic – one daughter dances through the rooms, Arthur’s mother writes plays, someone’s husband makes music, while others make fireworks in the basement.

Everyone in the family follows his credo – they all do whatever makes them happy. The household is therefore chaotic – one daughter dances through the rooms, Arthur’s mother writes plays, someone’s husband makes music, while others make fireworks in the basement. And that’s the film’s conflict and the source of its humour. The story is of how the Sycamore’s, who believe “you can’t take it with you,” win over the Kirby’s. (Well, Grandpa wins them over.)

And that’s the film’s conflict and the source of its humour. The story is of how the Sycamore’s, who believe “you can’t take it with you,” win over the Kirby’s. (Well, Grandpa wins them over.) And while the lead performers are all very good, the supporting cast is a bit weak – less because of their performances than by the fact they have little to do except run around making noise.

And while the lead performers are all very good, the supporting cast is a bit weak – less because of their performances than by the fact they have little to do except run around making noise.